1873 W. C. Handy*

1923 Francis Clay*

1924 Brewer Phillips*

1931 Hubert Sumlin*

1939 W. C. Clark*

1942 Chicago „Chi“ Coltrane*

1945 Paul Raymond*

1949 Big George Jackson*

1955 Christopher "Chris" Layton*

1958 Gianandrea Pasquinelli*

1965 Eden Brent*

1980 O. V. Wright+

1991 Jeradine Blues Mumma Hume*

Santos Puertas *

Happy Birthday

Brewer Phillips *16.11.1924

Brewer Phillips (* 16. November 1924 in Coila, Mississippi; † 30. August 1999 in Chicago, Illinois) war ein US-amerikanischer Bluesgitarrist. Bekannt wurde er als Mitglied von The HouseRockers, der Begleitband von Hound Dog Taylor.

Phillips wuchs auf einer Plantage auf, wo er schon in jungen Jahren von Memphis Minnie mit dem Blues bekannt gemacht wurde und wo er viele Bluesgrößen live hörte. Nachdem er nach Memphis umgezogen war, wurde er Profimusiker und spielte mit Bill Harvey und Roosevelt Sykes. 1960 wurde er Mitglied der HouseRockers, der Band von Hound Dog Taylor. Da die Band ohne Bass spielte, ahmte er die Basslinien oft auf seiner Gitarre nach. Nach dem Tod Taylors 1976 spielte er sporadisch mit J. B. Hutto, Lil’ Ed sowie mit Cub Koda und nahm Platten auf, blieb bis zu seinem Tod 1999 aber immer im Schatten der anderen Bluesgrößen Chicagos.

Brewer Phillips (November 16, 1924 – August 30, 1999)[1] was an American blues guitarist, chiefly associated with Juke joint blues and Chicago blues.

Phillips was born in Coila, Mississippi, United States, on a plantation and learned the blues from Memphis Minnie at an early age.[2] He relocated to Memphis and played with Bill Harvey, Roosevelt Sykes, and Hound Dog Taylor. Following Taylor's death in 1976, Phillips recorded under his own name, as well as playing with J. B. Hutto, Lil' Ed Williams, and Cub Koda amongst others.[2] He performed on both acoustic and electric guitar, and recorded for Delmark Records and JSP Records.

Phillips died of natural causes in Chicago, Illinois, in August 1999, at the age of 74.

Hubert Sumlin *16.11.1931

Hubert Sumlin (* 16. November 1931 in Greenwood, Mississippi; † 4. Dezember 2011 in Wayne, New Jersey[1]) war ein US-amerikanischer Blues-Gitarrist, der vor allem als Mitglied der Band von Howlin’ Wolf bekannt wurde.

Sumlin wurde in Mississippi geboren, zog aber in Alter von acht Jahren nach Hughes, Arkansas und wuchs dort auf. Ebenfalls mit acht Jahren begann er mit der Gitarre seines älteren Bruders zu spielen, bis seine Mutter kurz darauf einen kompletten Wochenlohn ausgab und ihm eine eigene Gitarre kaufte.[2] Sumlin begann seine musikalische Karriere mit dem Mundharmonika-Virtuosen James Cotton, mit dem er in Juke Joints, aber auch in einer Radiosendung spielte und zwar beim Sender KWM in West Memphis. Bei diesen Radiosendungen lernte Sumlin Howlin’ Wolf kennen, der dort ebenfalls auftrat und mit dem er 1954 nach Chicago ging. Auf der Bühne verbesserte er seine Technik und übernahm bald die Leadgitarre in der Band.[3] In den Anfangsjahren in Chicago wurde Sumlin vorübergehend von Muddy Waters für seine Band abgeworben, kehrte aber zu Howlin' Wolf zurück, da ihm das Touren mit Waters zu anstrengend wurde.[4][5]

Hubert Sumlins Gitarre ist bei etlichen der Hits von Howlin’ Wolf zu hören, darunter Wang Dang Doodle, Shake for Me, Hidden Charms, Three Hundred Pounds of Joy und Killing Floor. Das Gitarrespiel Sumlins wird von Bob Margolin, selbst Gitarrist, in Sumlins Biographie als "zwischen intensiv und legendär" bezeichnet.[6] Sumlin blieb bei Howlin' Wolf bis zu dessen Tod 1976. Zwischendurch trat er auch solo oder mit anderen Musikern auf, so z. B. bei der Europa-Tour 1964, als er mit Sunnyland Slim und Willie Dixon in Ost-Berlin spielte. 2008 wurde er in die Blues Hall of Fame aufgenommen.

1980 verließ er die Wolf-Gang, die nach Howlin’ Wolfs Tod unter der Leitung von Eddie Shaw weiter aufgetreten war, um eine Solokarriere zu starten. Sein legendärer Status als Gitarrist zeigt sich auch daran, dass viele berühmte Musiker Sumlin als entscheidenden Einfluss angaben - darunter Eric Clapton, Keith Richards, Robbie Robertson, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Jimmy Page und Jimi Hendrix. Die Rolling Stones, die von ihren Anfängen an Howlin' Wolf und seine Band bewundert hatten, sorgten 1965 dafür, dass die Howlin' Wolf Band mit Sumlin in der Sendung Shindig zu ihrem ersten und einzigen Auftritt im US-Fernsehen kamen (die Stones hatten Howlin' Wolfs Song Little Red Rooster gecovert).[7] Im Januar 2003 luden die Rolling Stones Hubert Sumlin ein, gemeinsam mit ihnen im Madison Square Garden zu spielen. Keith Richards produzierte und nahm 2000 ein Album mit ihm auf, weil er unbedingt Blues mit Hubert Sumlin spielen wollte. Das Album erschien 2003.[6]

Spielstil

Hubert Sumlins Gitarrenspiel war zuerst stark beeinflusst vom akustischen Delta Blues, und Sumlin lernte früh am Beispiel von Charlie Patton und Robert Johnson und machte dann zuerst in West Memphis mit Howlin Wolf und speziell nach seinem Umzug nach Chicago den Übergang zum elektrischen Chicago Blues mit. Howlin Wolf, der selbst noch mit Patton und Johnson gespielt hatte, gab ihm Mitte der 1950er Jahre seine erste elektrische Gitarre, eine Gibson Les Paul Goldtop.[8]

Sumlin spielte vor allem Fingerstyle, bereicherte diesen Stil aber um ungewöhnliche Improvisationen und gleichzeitig hoch kontrolliertes Spiel bei scheinbar wildem Schlagen auf die Saiten. Bob Margolin beschrieb seinen Stil wie folgt: "Wenn Hubert die Gitarre spielt, nimmt er dich mit in seine Welt des Blues, von Verzweiflung zum Überschwang, von feinster Anmut zu gröbster Gewalt, von Alles Vorbei zu Immer und Ewig. Sein Stil ist ganz und gar originell und sein eigener und jederzeit wiederzuerkennen."[9]

Auszeichnungen

2008 wurde Hubert Sumlin in die Blues Hall of Fame der Blues Foundation aufgenommen.[10] Ebenso war er Juror bei den fünften Independent Music Awards.

Der Rolling Stone listet Sumlin auf Platz 43 der 100 besten Gitarristen aller Zeiten[11].

Tod

Hubert Sumlin starb im Alter von 80 Jahren am 4. Dezember 2011 an Herzversagen in einem Krankenhaus in Wayne, New Jersey.[12] Bis ins hohe Alter war er noch live aufgetreten, wie z. B. im Sommer 2010 auf Eric Claptons Crossroads Festival.

Hubert Charles Sumlin (November 16, 1931 – December 4, 2011) was a Chicago blues guitarist and singer,[1] best known for his "wrenched, shattering bursts of notes, sudden cliff-hanger silences and daring rhythmic suspensions" as a member of Howlin' Wolf's band.[2] Sumlin was listed as number 43 in the Rolling Stone 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time.[3]

Biography

Born in Greenwood, Mississippi, Sumlin was raised in Hughes, Arkansas.[4] He got his first guitar when he was eight years old.[5] As a boy, Sumlin first met Howlin' Wolf by sneaking into a performance. When Wolf relocated from Memphis to Chicago in 1953, his long-time guitarist Willie Johnson chose not to join him. Upon his arrival in Chicago, Wolf first hired Chicago guitarist Jody Williams, and in 1954 Wolf invited Sumlin to relocate to Chicago to play second guitar in his Chicago-based band. Williams left the band in 1955, leaving Sumlin as the primary guitarist, a position he held almost continuously (except for a brief spell playing with Muddy Waters around 1956) for the remainder of Wolf's career. According to Sumlin, Howlin' Wolf sent Sumlin to a classical guitar instructor at the Chicago Conservatory of Music for a while to learn the keyboards and scales.[6] Sumlin played on the album Howlin' Wolf, also called The Rockin' Chair Album, which was named the third greatest guitar album of all time by Mojo magazine in 2004.[7][8]

Upon Wolf's death in 1976, Sumlin continued on with several other members of Wolf's band under the name "The Wolf Pack" until about 1980. Sumlin also recorded under his own name, beginning with a session from a tour of Europe with Wolf in 1964. His final solo effort was About Them Shoes, released in 2004 by Tone-Cool Records. He underwent lung removal surgery the same year, yet continued performing until just before his death. His final recording, just days before his demise, were tracks laid down for the Stephen Dale Petit album "Cracking The Code" (333 Records).

Sumlin was inducted into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame in 2008.[9] He was nominated for four Grammy Awards: in 1999 for the album Tribute to Howlin' Wolf with Henry Gray, Calvin Jones, Sam Lay, and Colin Linden, in 2000 for Legends with Pinetop Perkins, in 2006 for his solo project About Them Shoes (which featured performances by Keith Richards, Eric Clapton, Levon Helm, David Johansen and James Cotton) and in 2010 for his participation on Kenny Wayne Shepherd's Live! in Chicago. He won multiple Blues Music Awards, and was a judge for the fifth annual Independent Music Awards to support independent artists' careers.[10]

A resident of Totowa, New Jersey for 10 years before his death,[11] Sumlin died on December 4, 2011, in a hospital in Wayne, New Jersey, of heart failure at the age of 80.[12][13] Mick Jagger and Keith Richards paid Sumlin's funeral costs.

W. C. Clarke *16.11.1939

W. C. Clark (* 16. November 1939 in Austin, Texas, als Wesley Curley Clark) ist ein US-amerikanischer Bluesgitarrist, -sänger und -songwriter. Im Laufe seines Lebens erarbeitete er sich den Titel „The Godfather of Austin Blues“.

Clark wurde in eine musikalische Familie hineingeboren, denn sein Vater spielte Gitarre und seine Mutter und Großmutter sangen im Chor der St. John's College Baptist Church.[1] Blues war zwar nicht verboten, aber den größten Respekt musste er für Gospel haben.[2] Mit 14 begann er, Gitarre und Bass zu spielen, und bereits mit 16 trat er erstmals in Austin auf. In den nächsten Jahren wurde er ein wichtiger Teil der Bluesszene von Austin. Er trat mit verschiedenen wichtigen Musikern der Austin-Bluesszene auf, so z. B. mit Blues Boy Hubbard and The Jets.[3] Ende der 1960er Jahre wurde er Mitglied in der Band des Soulsängers Joe Tex und verließ Austin.

Er verließ die Band aber bald, um nach Austin zurückzukehren. Hier war er überrascht von der blühenden Bluesszene, die besonders von jungen, weißen Bluesmusikern getragen wurde, die oft von der nahen University of Texas kamen. Bill Campbell, Angela Strehli, Lewis Cowdrey, Paul Ray, Stevie Ray Vaughan und sein älterer Bruder Jimmie Vaughan zogen immer mehr Menschen an.[4] In den frühen 1970er-Jahren gründete er verschiedene Bands und entwickelte seine Fähigkeiten als Songwriter. Seine Anstrengungen um einen Plattenvertrag blieben aber vergeblich, und so arbeitete er als Mechaniker bei einem örtlichen Fordhändler.[5]

Dort besuchte ihn der junge Stevie Ray Vaughan und überzeugte ihn, Mitglied der Gruppe zu werden, die er gerade zusammenstellte. Er stimmte zu und gemeinsam mit der Sängerin Lou Ann Barton bildeten sie die „Triple Threat Revue“, in der Clark Bass spielte. Zu dieser Zeit schrieb er gemeinsam mit dem Keyboarder der Band „One Shot“, das für Vaughan zum größten Hit Mitte der 1980er-Jahre wurde. 1975 bildete Clark die W. C. Clark Blues Revue, eine Band, die die ganzen 1980er-Jahre mit Größen wie James Brown, B. B. King, Albert King, Freddie King, Sam and Dave, Elvin Bishop und Bobby Blue Bland unterwegs war. Mit ihr nahm er auch 1987 sein erstes Album, Something for Everybody, auf. Anfang der Dekade nahm er auch die späteren Rockwunderkinder Charlie Sexton and Will Sexton unter seine Fittiche und brachte ihnen das Gitarrespielen bei. 1990 sendete PSB ein Konzert im Rahmen ihrer Sendereihe Austin City Limits, das 1989 aus Anlass seines fünfzigsten Geburtstags aufgenommen wurde. Dieses Konzert machte ihn auch national bekannt. Mit Clark traten Stevie Ray Vaughan, Jimmie Vaughan, Kim Wilson, Lou Ann Barton, Angela Strehli und Will Sexton auf. Im März 1997 verunglückte der Bandbus, dabei starben seine Verlobte und der Schlagzeuger der Band. Zur Erinnerung an sie nahm er 1998 das Album Lover´s Plea auf. 2000 sendete PBS im Rahmen eines Stevie Ray Vaughan-Specials eine Jamsession mit ihm und W. C. Clark. In der ersten Dekade des neuen Jahrtausends ist W. C. Clark oft auf Bluesfestivals zu hören oder geht auf Tourneen. So erweitert er die Zahl seiner Fans immer mehr und auf der ganzen Welt kennt man jetzt den „Godfather of Austin Blues“.

W. C. Clark (born Wesley Curley Clark, November 16, 1939) is an American blues musician. He is known as the "Godfather of Austin Blues" for his influence on the Austin, Texas blues scene since the late 1960s.

Biography

Clark was born and raised in Austin, Texas, United States, where he sang gospel music in the choir as a young boy. In the early 1950s at age 14 he first learned the guitar, and then later experimented with blues and jazz on the bass guitar.

By the early 1960s, he began attracting the attention of such Texas blues performers as Big Joe Turner, Albert Collins and Little Johnny Taylor.

In the late 1960s, he joined the R&B Joe Tex Band, and left Austin, where he thought the R&B scene had died. But during a tour with the band back through Austin, Clark sat in on bass with younger Austin locals Jimmie Vaughan and Paul Ray at an East Austin club. After the session playing with Vaughan and Ray, Clark changed his mind about Austin.

He left Joe Tex two weeks later and moved back to Austin, where he then remained to guide and inspire numerous Austin musicians and lay the foundation of the prolific Austin blues and rock scene of the 1970s and later.

In the early 1970s, Clark formed an Austin blues quintet named Triple Threat Revue, with members Stevie Ray Vaughan and Lou Ann Barton. He also formed several bands with various names, which also included as members Jimmie Vaughan and Angela Strehli.

In 1975, Clark formed the W. C. Clark Blues Revue. Through the 1980s that band played venues with international greats such as James Brown, B.B. King, Albert King, Freddy King, Sam and Dave, Elvin Bishop and Bobby Blue Bland.

By the early 1980s Clark had taught future rock prodigy brothers Charlie Sexton and Will Sexton how to play guitar, while they were still young boys.

In 1990, Clark appeared on the PBS music television program Austin City Limits, with his group W. C. Clark Blues Revue, from a show taped October 10, 1989, in celebration of his 50th birthday, along with Stevie Ray Vaughan, Jimmie Vaughan and Kim Wilson of The Fabulous Thunderbirds, Lou Ann Barton, Angela Strehli and his former protégé, Will Sexton.[1]

In March 1997, on the eve of Austin's South by Southwest music festival, as Clark and his band were returning from a show in Milwaukee, their van, driven by Clark, veered off the highway and down a steep embankment near Sherman, Texas, injuring his arm and killing his fiancee Brenda Jasek and his drummer, Pedro Alcoser, Jr.[2] The album Lover's Plea followed, containing the single "Are You Here, Are You There?" in memory of Jasek.

W.C. Clark & Jimmie Vaughan - Talk Talk To Me

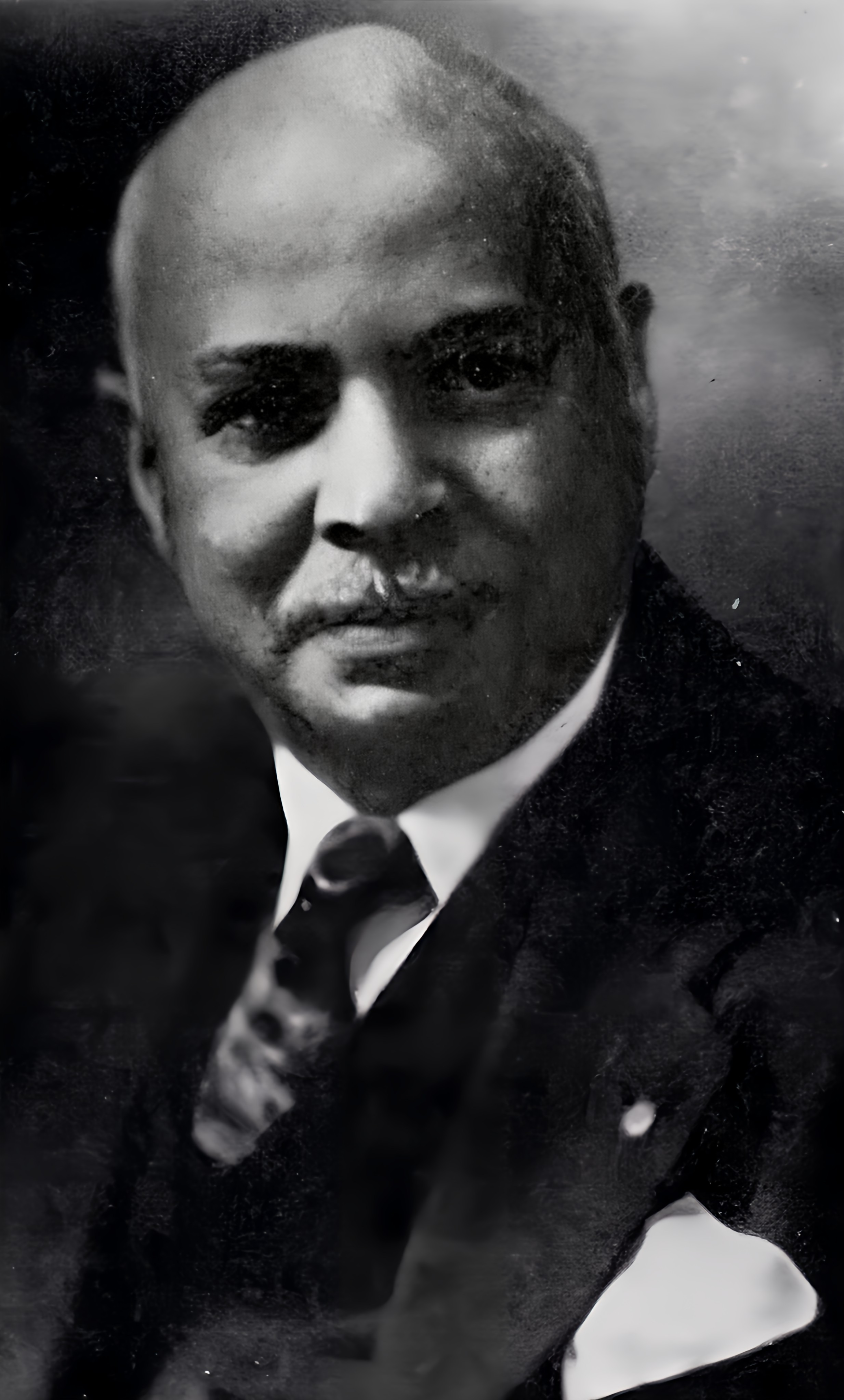

W. C. Handy *16.11.1873

Als Sohn freigelassener Sklaven fand W. C. Handy seine musikalischen Wurzeln in der Kirchenmusik und den Klängen der freien Natur, in der er aufwuchs. Er erlernte verschiedene Handwerke, doch kaufte er sich bald eine erste eigene Gitarre. Seine Eltern waren damit nicht einverstanden – für sie war Gitarrenmusik ein Zeichen der Sünde – und meldeten ihn zum Orgelunterricht an, was ihrer christlichen Überzeugung eher entsprach. Der junge William Christopher setzte jedoch seinen Kopf durch und anstelle der Orgel lernte er Trompete spielen.

Seine musikalischen Interessen waren vielfältig. Er sang in einer Minstrel Show und arbeitete als Bandleader, Chorleiter, Kornettist und Trompeter. Mit 23 Jahren leitete er die Band Mahara’s Colored Minstrels. 1893 spielte er auf der Weltausstellung in Chicago, 1902 tingelte er durch Mississippi, wo er mit der ursprünglichen Musik der einfachen Schwarzen in Berührung kam.

Am 19. Juli 1896 heiratete Handy Elizabeth Price. Kurz danach begann er seine Arbeit mit Mahara’s Minstrels, mit denen er drei Jahre lang für 6 Dollar Wochenlohn durch halb Amerika und Kuba reiste. Anschließend ließ sich das junge Paar in Huntsville in Alabama in der Nähe von Florence nieder, wo am 29. Juni 1900 das erste von sechs Kindern geboren wurde. Das zweite Kind war die Sängerin Katherine Handy (1902–1982).

Von 1900 bis 1902 war Handy als Musiklehrer an einem College für Schwarze tätig, bevor er wieder mit Mahara’s Minstrels auf Tour ging. Ab 1903 leitete er sechs Jahre lang eine schwarze Band, The Knights of Pythias, in Clarksdale in Mississippi.

1909 zog die Band nach Memphis, Tennessee, und richtete sich an der Beale Street ein; nach dieser Straße benannte er den Beale Street Blues, ein weiterer Meilenstein in der Entwicklung des Blues. In dieser Zeit entwickelte Handy aus seinen Beobachtungen der schwarzen Musik und der Reaktion der Weißen darauf den Stil, der später als Blues populär werden sollte. 1909 entstand der Memphis Blues, der 1912 veröffentlicht wurde und als das erste je veröffentlichte Bluesstück gilt. Das Stück machte Handy einem größeren Publikum bekannt. Auch soll es das New Yorker Tanzpaar Vernon und Irene Castle zur Entwicklung des Foxtrott inspiriert haben. Handy verkaufte die Rechte am Memphis Blues für 100 Dollar.

1917 zog Handy nach New York, wo er bessere Arbeitsbedingungen zu finden hoffte. Zur gleichen Zeit wurde Jazzmusik populär, und viele der Kompositionen Handys wurden zu Jazz-Standards. In den 1920ern eröffnete Handy seine eigene Plattenfirma Handy Record Company in New York.

Am 14. Januar 1925 machten Bessie Smith und Louis Armstrong mit Handys St. Louis Blues eine der besten Bluesaufnahmen der 1920er Jahre. 1926 brachte Handy eine Blues-Anthologie heraus, Blues: An Anthology: Complete Words and Music of 53 Great Songs, wahrscheinlich der erste Versuch, den Blues umfassend zu dokumentieren und als Teil der amerikanischen Kultur zu verstehen. Im Juni 1929 wurde ein Film gedreht, in dem Bessie Smith den St. Louis Blues sang und der bis 1932 als Vorfilm in Kinos überall in den Staaten gezeigt wurde. Der Siegeszug des Blues war nicht aufzuhalten.

1941 veröffentlichte Handy seine Autobiografie Father of the Blues: An Autobiography. 1944 erschien Unsung Americans Sing über schwarze amerikanische Musiker. Insgesamt schrieb Handy fünf Bücher (siehe unten).

Durch einen Unfall wurde Handy 1943 blind. Nach dem Tod seiner ersten Frau heiratete er 1954 im Alter von 80 Jahren seine Sekretärin Irma Louise Logan, die, wie er oft betonte, zu seinen Augen geworden war.

1955 erlitt Handy einen Schlaganfall und musste von da an einen Rollstuhl benutzen. Zu seinem 84. Geburtstag kamen über 800 Gäste ins Waldorf-Astoria-Hotel.

Am 28. März 1958 starb W. C. Handy. Mehr als 25.000 Menschen nahmen an seiner Bestattungsfeier in Harlem teil. Über 150.000 Menschen versammelten sich in den umliegenden Straßen. W. C. Handy ist auf dem Woodlawn-Friedhof im New Yorker Stadtteil Bronx bestattet.

William Christopher Handy (November 16, 1873 – March 28, 1958) was an American blues composer and musician.[1] He was widely known as the "Father of the Blues".[2]

Handy remains among the most influential of American songwriters. Though he was one of many musicians who played the distinctively American form of music known as the blues, he is credited with giving it its contemporary form. While Handy was not the first to publish music in the blues form, he took the blues from a regional music style (Delta blues) with a limited audience to one of the dominant national forces in American music.

Handy was an educated musician who used folk material in his compositions. He was scrupulous in documenting the sources of his works, which frequently combined stylistic influences from several performers.

Early life

Handy was born in Florence, Alabama, to parents Elizabeth Brewer, and Charles Barnard Handy. His father was the pastor of a small church in Guntersville, a small town in northeast central Alabama. Handy wrote in his 1941 autobiography, Father of the Blues, that he was born in the log cabin built by his grandfather William Wise Handy, who became an African Methodist Episcopal (AME) minister after emancipation. The log cabin of Handy's birth has been saved and preserved near downtown Florence.

Growing up he apprenticed in carpentry, shoemaking and plastering.

Handy was a deeply religious man, whose influences in his musical style were found in the church music he sang and played as a youth, and in the natural world. He later cited the sounds of nature, such as "whippoorwills, bats and hoot owls and their outlandish noises", the sounds of Cypress Creek washing on the fringes of the woodland, and "the music of every songbird and all the symphonies of their unpremeditated art" as inspiration.

Handy's father believed that musical instruments were tools of the devil.[3] Without his parents' permission, Handy bought his first guitar, which he had seen in a local shop window and secretly saved for by picking berries and nuts and making lye soap. Upon seeing the guitar, his father asked him, "What possessed you to bring a sinful thing like that into our Christian home?" Ordering Handy to "Take it back where it came from", his father quickly enrolled him in organ lessons. Handy's days as an organ student were short-lived, and he moved on to learn the cornet. Handy joined a local band as a teenager, but he kept this fact a secret from his parents. He purchased a cornet from a fellow band member and spent every free minute practicing it.

Musical development

He worked on a "shovel brigade" at the McNabb furnace, and described the music made by the workers as they beat shovels, altering the tone while thrusting and withdrawing the metal part against the iron buggies to pass the time while waiting for the overfilled furnace to digest its ore. "With a dozen men participating, the effect was sometimes remarkable...It was better to us than the music of a martial drum corps, and our rhythms were far more complicated."[4] He wrote, "Southern Negroes sang about everything....They accompany themselves on anything from which they can extract a musical sound or rhythmical effect..." He would later reflect that, "In this way, and from these materials, they set the mood for what we now call blues".[5]

In September 1892, Handy travelled to Birmingham, Alabama, to take a teaching exam, which he passed easily, and gained a teaching job in the city. Learning that it paid poorly, he quit the position and found industrial work at a pipe works plant in nearby Bessemer.

During his off-time, he organized a small string orchestra and taught musicians how to read notes. Later, Handy organized the Lauzetta Quartet. When the group read about the upcoming World's Fair in Chicago, they decided to attend. To pay their way, group members performed at odd jobs along the way. They arrived in Chicago only to learn that the World's Fair had been postponed for a year. Next they headed to St. Louis, Missouri but found working conditions very bad.

After the quartet disbanded, Handy went to Evansville, Indiana, where he helped introduce the blues. He played cornet in the Chicago World's Fair in 1893. In Evansville, Handy joined a successful band that performed throughout the neighboring cities and states. His musical endeavors were varied: he sang first tenor in a minstrel show, worked as a band director, choral director, cornetist and trumpeter.

At the age of 23, Handy became band master of Mahara's Colored Minstrels. In their three-year tour, they traveled to Chicago, throughout Texas and Oklahoma, through Tennessee, Georgia and Florida, and on to Cuba. Handy earned a salary of $6 per week. Returning from Cuba, the band traveled north through Alabama, and stopped to perform in Huntsville. Weary of life on the road, he and his wife Elizabeth decided to stay with relatives in his nearby hometown of Florence.

Marriage and family

In 1896 while performing at a barbecue in Henderson, Kentucky, Handy met Elizabeth Price. They married shortly afterward on July 19, 1896. She had Lucille, the first of their six children, on June 29, 1900, after they had settled in Florence, Alabama, his hometown.

Teaching music

Around that time, William Hooper Councill, President of Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical College for Negroes (AAMC) (today named Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical University) in Normal, Alabama, recruited Handy to teach music at the college. Handy became a faculty member in September 1900 and taught through much of 1902.

His enthusiasm for the distinctive style of uniquely American music, then often considered inferior to European classical music, was part of his development. He was disheartened to discover that the college emphasized teaching European music considered to be "classical". Handy felt he was underpaid and could make more money touring with a minstrel group.

Studying the blues

In 1902 Handy traveled throughout Mississippi, where he listened to the various black popular musical styles. The state was mostly rural, and music was part of the culture, especially of the Mississippi Delta cotton plantation areas. Musicians usually played the guitar, banjo, and to a much lesser extent, the piano. Handy's remarkable memory enabled him to recall and transcribe the music heard in his travels.

After a dispute with AAMC President Councill, Handy resigned his teaching position to rejoin the Mahara Minstrels and tour the Midwest and Pacific Northwest. In 1903 he became the director of a black band organized by the Knights of Pythias, located in Clarksdale, Mississippi. Handy and his family lived there for six years. In 1903 while waiting for a train in Tutwiler in the Mississippi Delta, Handy had the following experience:

A lean loose-jointed Negro had commenced plunking a guitar beside me while I slept... As he played, he pressed a knife on the strings of the guitar in a manner popularized by Hawaiian guitarists who used steel bars....The singer repeated the line three times, accompanying himself on the guitar with the weirdest music I had ever heard.[5][6]

About 1905 while playing a dance in Cleveland, Mississippi, Handy was given a note asking for "our native music".[7] He played an old-time Southern melody, but was asked if a local colored band could play a few numbers. Three young men with a battered guitar, mandolin, and a worn-out bass took the stage.[8] [9]

They struck up one of those over and over strains that seem to have no beginning and certainly no ending at all. The strumming attained a disturbing monotony, but on and on it went, a kind of stuff associated with [sugar] cane rows and levee camps. Thump-thump-thump went their feet on the floor. It was not really annoying or unpleasant. Perhaps "haunting" is the better word.[8][10]

Handy noted square dancing by Mississippi blacks with "one of their own calling the figures, and crooning all of his calls in the key of G."[11] He remembered this when deciding on the key for "St Louis Blues".

It was the memory of that old gent who called figures for the Kentucky breakdown—the one who everlastingly pitched his tones in the key of G and moaned the calls like a presiding elder preaching at a revival meeting. Ah, there was my key – I'd do the song in G.[12]

In describing "blind singers and footloose bards" around Clarksdale, Handy wrote, "[S]urrounded by crowds of country folks, they would pour their hearts out in song ... They earned their living by selling their own songs – "ballets," as they called them—and I'm ready to say in their behalf that seldom did their creations lack imagination."[13]

Transition: popularity, fame and business

In 1909 Handy and his band moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where they started playing at clubs on Beale Street. The genesis of his "Memphis Blues" was as a campaign tune written for Edward Crump, a successful Memphis mayoral candidate in 1909 (and future "boss"). Handy later rewrote the tune and changed its name from "Mr. Crump" to "Memphis Blues."

The 1912 publication of his "Memphis Blues" sheet music introduced his style of 12-bar blues; it was credited as the inspiration for the foxtrot dance step by Vernon and Irene Castle, a New York–based dance team. Some consider it to be the first blues song. Handy sold the rights to the song for US$100. By 1914, when Handy was 40, he had established his musical style, his popularity increased significantly, and he composed prolifically.

Handy wrote about using folk songs:

The primitive southern Negro, as he sang, was sure to bear down on the third and seventh tone of the scale, slurring between major and minor. Whether in the cotton field of the Delta or on the Levee up St. Louis way, it was always the same. Till then, however, I had never heard this slur used by a more sophisticated Negro, or by any white man. I tried to convey this effect... by introducing flat thirds and sevenths (now called blue notes) into my song, although its prevailing key was major..., and I carried this device into my melody as well... This was a distinct departure, but as it turned out, it touched the spot.[14]

W. C. Handy with his 1918 Memphis Orchestra: Handy is center rear, holding trumpet.

The three-line structure I employed in my lyric was suggested by a song I heard Phil Jones sing in Evansville ... While I took the three-line stanza as a model for my lyric, I found its repetition too monotonous ... Consequently I adopted the style of making a statement, repeating the statement in the second line, and then telling in the third line why the statement was made.[15]

Regarding the "three-chord basic harmonic structure" of the blues, Handy wrote the "(tonic, subdominant, dominant seventh) was that already used by Negro roustabouts, honky-tonk piano players, wanderers and others of the underprivileged but undaunted class from Missouri to the Gulf, and had become a common medium through which any such individual might express his personal feeling in a sort of musical soliloquy."[14] He noted,

In the folk blues the singer fills up occasional gaps with words like 'Oh, lawdy' or 'Oh, baby' and the like. This meant that in writing a melody to be sung in the blues manner one would have to provide gaps or waits.[16]

Writing about the first time "St Louis Blues" was played (1914), Handy said,

The one-step and other dances had been done to the tempo of Memphis Blues.... When St Louis Blues was written the tango was in vogue. I tricked the dancers by arranging a tango introduction, breaking abruptly into a low-down blues. My eyes swept the floor anxiously, then suddenly I saw lightning strike. The dancers seemed electrified. Something within them came suddenly to life. An instinct that wanted so much to live, to fling its arms to spread joy, took them by the heels.[17]

His published musical works were groundbreaking because of his ethnicity, and he was among the first blacks to achieve economic success because of publishing. In 1912, Handy met Harry H. Pace at the Solvent Savings Bank in Memphis. Pace was valedictorian of his graduating class at Atlanta University and student of W. E. B. Du Bois. By the time of their meeting, Pace had already demonstrated a strong understanding of business. He earned his reputation by recreating failing businesses. Handy liked him, and Pace later became manager of Pace and Handy Sheet Music.

While in New York City, Handy wrote:

I was under the impression that these Negro musicians would jump at the chance to patronize one of their own publishers. They didn't... The Negro musicians simply played the hits of the day...They followed the parade. Many white bands and orchestra leaders, on the other hand, were on the alert for novelties. They were therefore the ones most ready to introduce our numbers. [But,] Negro vaudeville artists...wanted songs that would not conflict with white acts on the bill. The result was that these performers became our most effective pluggers.[18]

In 1917, he and his publishing business moved to New York City, where he had offices in the Gaiety Theatre office building in Times Square.[19] By the end of that year, his most successful songs: "Memphis Blues", "Beale Street Blues", and "Saint Louis Blues", had been published. That year the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, a white New Orleans jazz ensemble, had recorded the first jazz record, introducing the style to a wide segment of the American public. Handy initially had little fondness for this new "jazz", but bands dove into his repertoire with enthusiasm, making many of them jazz standards.

Handy encouraged performers such as Al Bernard, "a young white man" with a "soft Southern accent" who "could sing all my Blues". Handy sent Bernard to Thomas Edison to be recorded, which resulted in "an impressive series of successes for the young artist, successes in which we proudly shared." Handy also published the original "Shake Rattle and Roll" and "Saxophone Blues", both written by Bernard. "Two young white ladies from Selma, Alabama (Madelyn Sheppard and Annelu Burns) contributed the songs "Pickaninny Rose" and "O Saroo", with the music published by Handy's company. These numbers, plus our blues, gave us a reputation as publishers of Negro music."[20]

Expecting to make only "another hundred or so" on a third recording of his "Yellow Dog Blues" (originally titled "Yellow Dog Rag"[21] ), Handy signed a deal with the Victor company. The Joe Smith[22] recording of this song in 1919 became the best-selling recording of Handy's music to date.[23][24]

Handy tried to interest black women singers in his music, but initially was unsuccessful. In 1920 Perry Bradford persuaded Mamie Smith to record two of his non-blues songs, published by Handy, accompanied by a white band: "That Thing Called Love" and "You Can't Keep a Good Man Down". When Bradford's "Crazy Blues" became a hit as recorded by Smith, African-American blues singers became increasingly popular. Handy found his business began to decrease because of the competition.[25]

In 1920 Pace amicably dissolved his long-standing partnership with Handy, with whom he also collaborated as lyricist. As Handy wrote: "To add to my woes, my partner withdrew from the business. He disagreed with some of my business methods, but no harsh words were involved. He simply chose this time to sever connection with our firm in order that he might organize Pace Phonograph Company, issuing Black Swan Records and making a serious bid for the Negro market. . . . With Pace went a large number of our employees. . . . Still more confusion and anguish grew out of the fact that people did not generally know that I had no stake in the Black Swan Record Company."[26]

Although Handy's partnership with Pace was dissolved, he continued to operate the publishing company as a family-owned business. He published works of other black composers as well as his own, which included more than 150 sacred compositions and folk song arrangements and about 60 blues compositions. In the 1920s, he founded the Handy Record Company in New York City. Bessie Smith's January 14, 1925, Columbia Records recording of "Saint Louis Blues" with Louis Armstrong is considered by many to be one of the finest recordings of the 1920s. So successful was Handy's "Saint Louis Blues" that in 1929, he and director [Dudley Murphy] collaborated on a RCA motion picture project of the same name, which was to be shown before the main attraction. Handy suggested blues singer Bessie Smith have the starring role, since she had gained widespread popularity with that tune. The picture was shot in June and was shown in movie houses throughout the United States from 1929 to 1932.

In 1926 Handy authored and edited a work entitled Blues: An Anthology—Complete Words and Music of 53 Great Songs. It is probably the first work that attempted to record, analyze and describe the blues as an integral part of the U.S. South and the history of the United States. To celebrate the books release and to honor Handy, Small's Paradise in Harlem hosted a party Handy Night on Tuesday October 5, which contained the best of jazz and blues selections provided by the entertainers Adelaide Hall, Lottie Gee, Maude White and Chic Collins.[27]

The genre of the blues was a hallmark of American society and culture in the 1920s and 1930s. So great was its influence, and so much was it recognized as Handy's hallmark, that author F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote in his novel The Great Gatsby that "All night the saxophones wailed the hopeless comment of the "Beale Street Blues" while a hundred pairs of golden and silver slippers shuffled the shining dust. At the gray tea hour there were always rooms that throbbed incessantly with this low, sweet fever, while fresh faces drifted here and there like rose petals blown by the sad horns around the floor."

Later life

Following publication of his autobiography, Handy published a book on African-American musicians entitled Unsung Americans Sing (1944). He wrote a total of five books:

Blues: An Anthology: Complete Words and Music of 53 Great Songs

Book of Negro Spirituals

Father of the Blues: An Autobiography

Unsung Americans Sing

Negro Authors and Composers of the United States

During this time, he lived on Strivers' Row in Harlem. He became blind following an accidental fall from a subway platform in 1943. After the death of his first wife, he remarried in 1954, when he was 80. His new bride was his secretary, the former Irma Louise Logan, whom he frequently said had become his eyes.

In 1955, Handy suffered a stroke, following which he began to use a wheelchair. More than eight hundred attended his 84th birthday party at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel.

Death

On March 28, 1958 he died of bronchial pneumonia at Sydenham Hospital in New York City.[28] Over 25,000 people attended his funeral in Harlem's Abyssinian Baptist Church. Over 150,000 people gathered in the streets near the church to pay their respects. He was buried in the Woodlawn Cemetery in Bronx, New York.

Compositions

Handy's songs do not always follow the classic 12-bar pattern, often having 8- or 16-bar bridges between 12-bar verses.

"Memphis Blues", written 1909, published 1912. Although usually subtitled "Boss Crump", it

is a distinct song from Handy's campaign satire, "Boss Crump don't 'low no easy riders around

here", which was based on the good-time song "Mamma Don't Allow It."

"Yellow Dog Blues" (1912), "Your easy rider's gone where the Southern cross the Yellow Dog."

The reference is to the crossing at Moorhead, Mississippi, of the Southern Railway and the

local Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroad, called the Yellow Dog. By Handy's telling locals

assigned the words "Yellow Dog" to the letters Y.D.(for Yazoo Delta) on the freight trains that

they saw.[29]

"Saint Louis Blues" (1914), "the jazzman's Hamlet."

"Loveless Love", based in part on the classic, "Careless Love". Possibly the first song to

complain of modern synthetics, "with milkless milk and silkless silk, we're growing used to

soulless soul."

"Aunt Hagar's Blues", the biblical Hagar, handmaiden to Abraham and Sarah, was considered

the "mother" of the African Americans.

"Beale Street Blues" (1916), written as a farewell to the old Beale Street of Memphis (actually

called Beale Avenue until the song changed the name); but Beale Street did not go away and

is considered the "home of the blues" to this day. B.B. King was known as the "Beale Street

Blues Boy" and Elvis Presley watched and learned from Ike Turner there. In 2004 the tune was

included as a track on the Memphis Jazz Box compilation as a tribute to Handy and his music.

"Long Gone John (From Bowling Green)", tribute to a famous bank robber.

"Chantez-Les-Bas (Sing 'Em Low)", tribute to the Creole culture of New Orleans.

"Atlanta Blues", includes the song known as "Make Me a Pallet on your Floor" as its chorus.

"Ole Miss Rag" (1917), a ragtime composition, recorded by Handy's Orchestra of

Memphis.[30]

Awards, festivals and memorials

The Blues Music Award, widely recognized as the most prestigious award for blues artists was

known as the W. C. Handy Award until the name change in 2006.

The W. C. Handy Music Festival is held annually in Florence, Alabama and the greater Shoals

area. The festival has evolved into a 10-day-long celebration that includes a parade, various

artists at restaurants and venues around town, and larger music events at Wilson Park in

downtown Florence. The park features a statue of Handy and is close to his birthplace and

museum. Previous festivals have featured jazz and blues legends including Jimmy Smith,

Ramsey Lewis, Dizzy Gillespie, Bobby Blue Bland, Diane Schuur, Billy Taylor, Dianne Reeves

and Charlie Byrd, Ellis Marsalis and Take 6. The festival also features a roster of annual

regulars, called the W. C. Handy Jazz All-Stars.[32]

W. C. Handy Park is a city park located on Beale Street in Memphis, Tennessee. The park

contains a life-sized bronze statue of Handy.

The W.C. Handy Blues & Barbeque Festival is a week-long musical event that features blues

and Zydeco bands from across the U.S and is held every June on the banks of the Ohio River

in downtown Henderson, Kentucky.

In 1979, New York City joined the list of institutions and municipalities to honor Handy by

naming one block of West 52nd Street in Manhattan "W.C. Handy Place".

Francis Clay *16.11.2013

Francis Clay (November 16, 1923 – January 21, 2008), was a jazz and blues drummer, best known for his work behind Muddy Waters in the '50s and '60s and as an original member of the James Cotton band. Clay's jazz-influenced style is cited as an influence by many of the British Invasion rock 'n' rollers of the '60s such as Charlie Watts[1] and Ronnie Wood of the Rolling Stones and Faces, respectively.

Born and raised in Rock Island, Illinois, he started playing jazz, professionally at the age of 15, played drums behind many of the biggest names of 20th century popular American music.

In his career, Clay claimed to have backed Gypsy Rose Lee, and played with Jay McShann and Charlie Parker early on and with Jimi Hendrix while in New York's Greenwich Village. He can be heard on recordings including John Lee Hooker's Live at the Cafe Au Go-Go and can be seen and heard on documents from the Waters band's 1960 Newport Jazz Festival appearance and on albums issued by the El Cerrito, California Arhoolie label by Big Mama Thornton and Lightning Hopkins, among many others.

Clay made his home in San Francisco in the late 1960s and became a part of the music scene in the Bay Area throughout the rest of his life. His birthday parties at the Biscuits and Blues nightclub were an annual gathering of the tribe, and he was known also as "the ambassador" at the annual San Francisco Blues Festival, where he was the subject of a tribute in 2007, and mourned in 2008.

Clay claimed to have been deprived of recognition for his compositional contributions to the Waters oeuvre. Songs he claimed to have composed and/or arranged included "Walking in the Park," "She's Nineteen Years Old" and "Tiger in Your Hole."

Muddy Waters Band, Got My Mojo Working---Live at Newport Jazz Festival, July 3 1960

The Band:

Pat Hare (Guitar)

Otis Spann (Piano)

James Cotton (Harmonica)

Andrew Stephenson (Bass)

Francis Clay (Drums)

Pat Hare (Guitar)

Otis Spann (Piano)

James Cotton (Harmonica)

Andrew Stephenson (Bass)

Francis Clay (Drums)

Einer der wenigen, die ihre Europäischen Fans trotzdem nicht im Stich lassen, ist der 1949 geborene Sänger und Harmonikaspieler BIG GEORGE JACKSON, in seiner Heimat bekannt als "the big man of the blues".

BIG GEORGE JACKSON verfügt über eine rauhe, tiefe, überaus angenehme Stimme und sein Repertoire besteht überwiegend aus Eigenkompositionen, aber auch Coversongs, die sich alle im Stil der 50er und 60er bewegen. Der Mann hat Ecken und Kanten. BIG GEORGE erweist sich immer wieder als kräftiger, ausdrucksstarker Sänger mit Wiedererkennungswert, seine Harmonika kommt so richtig schön dreckig und sein Boogie grummelt herrlich in John Lee Hooker - Manier vor sich hin! Überhaupt hält sich BIG GEORGE JACKSON erst gar nicht gross mit langsamen Nummern auf.

BIG GEORGE JACKSON verfügt über eine rauhe, tiefe, überaus angenehme Stimme und sein Repertoire besteht überwiegend aus Eigenkompositionen, aber auch Coversongs, die sich alle im Stil der 50er und 60er bewegen. Der Mann hat Ecken und Kanten. BIG GEORGE erweist sich immer wieder als kräftiger, ausdrucksstarker Sänger mit Wiedererkennungswert, seine Harmonika kommt so richtig schön dreckig und sein Boogie grummelt herrlich in John Lee Hooker - Manier vor sich hin! Überhaupt hält sich BIG GEORGE JACKSON erst gar nicht gross mit langsamen Nummern auf.

Vocalist/harmonica player Big George Jackson was born November 16, 1949 and in the Twin Cities he is known as the authentic big man of the blues. He sings with a distinctive bass-rich voice only a six-foot, six inch gentle giant could be blessed with. Add his fat harmonica playing, dead-on phrasing, commanding stage-presence and instant audience rapport and it's easy to understand why the audience howl when he delivers his music.

Paul Martin Raymond (* 16. November 1945 in St Albans, Hertfordshire, England) ist ein britischer Keyboarder und Gitarrist.

Karriere

Mit 17 Jahren begann nach eigenen Angaben Raymonds dessen Karriere im Jazz-Bereich, nachdem er eine Anzeige in lokale Musikzeitschriften stellte. Er spielte ab Januar 1964 mit vielen verschiedenen Musikern, unter anderem der Bassist Dave Green war dabei. Er stieß zum Ian Bird Quintett und spielte mit diesen öfters in Blackheath. 1967 spielte Raymond in seiner ersten Band Plastic Penny, die sich der Popmusik verschrieben hatten. Andere bekannte Mitglieder waren Nigel Olsson und Mick Grabham. 1968 löste sich die Gruppe nach dem Album Two Sides of a Penny auf. 1969 und 1970 kamen noch zwei Alben auf den Markt, die vor der Trennung eingespielt worden waren. Daraufhin hörte er, dass Christine Perfect die Band Chicken Shack verlassen hatte, um John McVie zu heiraten. Er bewarb sich für den Job und erlernte mit Hilfe von Nigel Olsson, Hammond-Orgel zu spielen. Er stieß 1969 zu Chicken Shack. Nach den Alben 100 Ton Chicken und Accept verließ er die Band 1971 wieder. Er schloss sich direkt Savoy Brown an und blieb dort bis 1976. Nachdem UFO 1976 das Album No Heavy Petting mit Keyboarder Danny Peyronel veröffentlicht hatten, tourte Paul Raymond mit der Band im Vorprogramm von Rainbow um das Album zu promoten. 1977 erschien das Album Lights Out, auf dem Raymond erstmals Keyboard spielte. Nach dem Album Obsession 1978 verließ jedoch der deutsche Gitarrist Michael Schenker die Band, was zum Verfall führte. Auch auf dem Live-Album Strangers In The Night spielt er Keyboards und Gitarre. 1981 bis 1982 war er in der Michael Schenker Group aktiv und ist auf dem Album MSG und dem Live-Album One Night At Budokan zu hören. 1983 schloss er sich Pete Ways Band Waysted an und ist auf dem Debütalbum Vices (1983) zu hören. 1984 kehrte er zu UFO zurück, bei denen von der Originalbesetzung nur noch Phil Mogg übrig geblieben war. Nach dem Album Misdemeanor (1985) verließ er die Band jedoch 1986 erneut.

1993 kehrte er zu UFO zurück, da diese sich wieder vereinigt hatten. Jedoch geht aus dieser Zusammenarbeit nur das Album Walk On Water hervor, da Raymond 1999 schon wieder ausgeschieden war. Er ist jedoch seit 2003 wieder festes Mitglied bei UFO. Er ist auch gelegentlich bei Projekten von Michael Schenker zu hören.

Karriere

Mit 17 Jahren begann nach eigenen Angaben Raymonds dessen Karriere im Jazz-Bereich, nachdem er eine Anzeige in lokale Musikzeitschriften stellte. Er spielte ab Januar 1964 mit vielen verschiedenen Musikern, unter anderem der Bassist Dave Green war dabei. Er stieß zum Ian Bird Quintett und spielte mit diesen öfters in Blackheath. 1967 spielte Raymond in seiner ersten Band Plastic Penny, die sich der Popmusik verschrieben hatten. Andere bekannte Mitglieder waren Nigel Olsson und Mick Grabham. 1968 löste sich die Gruppe nach dem Album Two Sides of a Penny auf. 1969 und 1970 kamen noch zwei Alben auf den Markt, die vor der Trennung eingespielt worden waren. Daraufhin hörte er, dass Christine Perfect die Band Chicken Shack verlassen hatte, um John McVie zu heiraten. Er bewarb sich für den Job und erlernte mit Hilfe von Nigel Olsson, Hammond-Orgel zu spielen. Er stieß 1969 zu Chicken Shack. Nach den Alben 100 Ton Chicken und Accept verließ er die Band 1971 wieder. Er schloss sich direkt Savoy Brown an und blieb dort bis 1976. Nachdem UFO 1976 das Album No Heavy Petting mit Keyboarder Danny Peyronel veröffentlicht hatten, tourte Paul Raymond mit der Band im Vorprogramm von Rainbow um das Album zu promoten. 1977 erschien das Album Lights Out, auf dem Raymond erstmals Keyboard spielte. Nach dem Album Obsession 1978 verließ jedoch der deutsche Gitarrist Michael Schenker die Band, was zum Verfall führte. Auch auf dem Live-Album Strangers In The Night spielt er Keyboards und Gitarre. 1981 bis 1982 war er in der Michael Schenker Group aktiv und ist auf dem Album MSG und dem Live-Album One Night At Budokan zu hören. 1983 schloss er sich Pete Ways Band Waysted an und ist auf dem Debütalbum Vices (1983) zu hören. 1984 kehrte er zu UFO zurück, bei denen von der Originalbesetzung nur noch Phil Mogg übrig geblieben war. Nach dem Album Misdemeanor (1985) verließ er die Band jedoch 1986 erneut.

1993 kehrte er zu UFO zurück, da diese sich wieder vereinigt hatten. Jedoch geht aus dieser Zusammenarbeit nur das Album Walk On Water hervor, da Raymond 1999 schon wieder ausgeschieden war. Er ist jedoch seit 2003 wieder festes Mitglied bei UFO. Er ist auch gelegentlich bei Projekten von Michael Schenker zu hören.

Reuben Archers Personal Sin feat Paul Raymond - Reubens Blues

Santos Puertas *16.11.

http://www.santospuertas.com/

The Suitcase Brothers

Santos wurde am selben Tag wie WC Handy in einer kleinen Stadt namens Egham am Stadtrand von Barcelona geboren. Er hat sein musikalisches Talent, Entschlossenheit, Anstrengung und Leidenschaft zu erfassen und zum Ausdruck bringen durch die Gitarre und Gesang, Ton und Essenz des Blues und amerikanischen Wurzeln Musik.

Santos ist ein weiterer Beweis, dass Musik ist die universelle Sprache. Es ist die Musik, die Sie eine und nicht das andere zu wählen.

Nach einer Karriere von über 20 Jahren, schließlich im Jahr 2012 zog er nach Dallas, TX, wo seine Solo-Karriere, die mit den "Koffer Brothers beginnt, das Duo aus Blues und americana als vor 15 Jahren mit geformt kombiniert sein Bruder Victor Gates.

Im Jahr 2013 die "Suitcase Brüder gewann den zweiten Preis in der Kategorie Solo / Duo des Internationalen Blues Challenge, dem Internationalen Wettbewerb bekanntesten Blues und beschäftigt, die sich in Memphis, USA.

Im Jahr 2014 gewann den 1. Preis im Solo / Duo Wettbewerb auf dem Piedmont Blues Blues Preservation Society in Greensboro, North Carolina, USA.

Türen Santos durchgeführt und / oder in den Vereinigten Staaten registriert: Jerry Portnoy, Paul Osher, Dave Biller, Michael Linder, Joel Foy, Christian Dozzler, Miss Lavelle White, Fred Kaplan und Nathan James.

In Spanien er durchgeführt und / oder aufgezeichnet: Blas Picon, Lluís Coloma, Mario Cobo, Ivan Kovacevic, Dani Nel • lo, Anton Jarl, Big Mama Montse, Amadeu Casas, Artur Regada, Bernat Font, Reginald Vilardell, Santi Ursul, Big Dani Perez und Marc Ruiz.

Derzeit arbeitet er an seinem neuen Solo-Projekt zu arbeiten und hat die vierte Album mit "Suitcase Brothers in Austin, TX (USA), die bereits auf dem Markt ist aufgezeichnet freigegeben.

Nach einer Karriere von über 20 Jahren, schließlich im Jahr 2012 zog er nach Dallas, TX, wo seine Solo-Karriere, die mit den "Koffer Brothers beginnt, das Duo aus Blues und americana als vor 15 Jahren mit geformt kombiniert sein Bruder Victor Gates.

Im Jahr 2013 die "Suitcase Brüder gewann den zweiten Preis in der Kategorie Solo / Duo des Internationalen Blues Challenge, dem Internationalen Wettbewerb bekanntesten Blues und beschäftigt, die sich in Memphis, USA.

Im Jahr 2014 gewann den 1. Preis im Solo / Duo Wettbewerb auf dem Piedmont Blues Blues Preservation Society in Greensboro, North Carolina, USA.

Türen Santos durchgeführt und / oder in den Vereinigten Staaten registriert: Jerry Portnoy, Paul Osher, Dave Biller, Michael Linder, Joel Foy, Christian Dozzler, Miss Lavelle White, Fred Kaplan und Nathan James.

In Spanien er durchgeführt und / oder aufgezeichnet: Blas Picon, Lluís Coloma, Mario Cobo, Ivan Kovacevic, Dani Nel • lo, Anton Jarl, Big Mama Montse, Amadeu Casas, Artur Regada, Bernat Font, Reginald Vilardell, Santi Ursul, Big Dani Perez und Marc Ruiz.

Derzeit arbeitet er an seinem neuen Solo-Projekt zu arbeiten und hat die vierte Album mit "Suitcase Brothers in Austin, TX (USA), die bereits auf dem Markt ist aufgezeichnet freigegeben.

At the end of the second set a fan approaches Santos and starts a conversation.

Santos Puertas senses that at some point in the conversation he is going to be asked:

-Where are you from? Why do you speak with an accent? …

Santos is the perfect example that the music chooses you, you don’t choose the music.

When one listens to Santos Puertas singing and playing american music, it’s hard to believe that he was born in a small town called Sant Just Desvern, on the outskirts of Barcelona, Spain.

Singing came naturally to him from an early age.It is in his blood. His grandfather and his mother were gifted singers. Santos remembers that they use to sing around the house and at every celebration. Guitar is the instrument Santos chose to accompany his voice.

The story of Santos Puertas (formerly known as Pere Puertas) is a story full of effort, passion and determination. At the age of 16, Santos was loading and unloading trucks to make enough money to pay for his first electric guitar and a little amp.

When he was 18, he worked in a factory, and with the money he earned he went to London, UK. He lived there for a year working as a dishwasher and a waiter during the day and playing guitar at night.

He started his first blues band when he was 19, soon after he came back from England to his home town, and started teaching English lessons for the first time.

When he dropped out of his last year of college at 23, he focused on earning a living and playing music.

He was a substitute teacher at the American school in Barcelona and taught English in Spanish schools.Soon he would start getting paid to play gigs too.

In the year 2000 Santos crossed the pond for the first time and went to Austin, TX. He made a bunch of musician friends and felt very welcome in the blues scene. The same year, together with his brother Victor Puertas, harmonica virtuoso and gifted musician, started the great piedmont blues americana duo called ‘The

Suitcase Brothers’. Also in the year 2000 they cut their first record, ‘Living with the Blues’. Some of Santos’ students are featured in that first recording singing the song ‘Down by the Riverside’.

After playing together for 15 years, 4 recordings, 2 movie soundtracks and hundreds of gigs and venues, the duo has become an important reference in the blues scene in Spain and Europe. They also love to play with a rhythm section when they can. They participated at the IBC (International Blues Challenge) 2013 in Memphis, and ended up winning 2nd place among 100 others international blues acts. They started touring and making U.S. fans.

They have recently released their 4th album, named ‘A Long Way from Home’, recorded in Austin, Texas, which features friend and blues harmonica legend Jerry Portnoy, among others. This last recording has garnered a number of great reviews in Europe and the US and it was among the five finalists for the ‘Best Self Produced CD’ category at the IBC in 2015.

After the first trip to Austin, TX in 2000, Santos continued going back until in the summer of 2003, when he joined the soul singer Miss Lavelle White’s band and toured with her in Texas.

He has also been deeply involved in the blues scene in Barcelona, doing all sorts of collaborations such as: translating the late John Cephas and James Harman workshops, teaching blues guitar, and conducting a blues radio show called ‘Just Blues’ in his hometown for 2 years.

Santos has opened and/or jamed with many blues artists such as: Hubert Sumlin, Bob Margolin, Hook Herrera, Steve James, Gary Primich, Nick Curran, John Cephas & Phil Wiggins, Paul Rishell & Annie Raines, and Hash Brown, among many others Santos has recorded and/or played with Jerry Portnoy, Paul Oscher, Miss Lavelle White, Joel Foy, Christian Dozzler, Fred Kaplan, Mike Morgan, and Nathan James, among others.

For more than twenty years Santos has dedicated his talent to play Americana, blues, and roots music and has become a respected player and stellar performer. He moved to Dallas, TX in 2012 where he lives, performs and teaches when he is not touring in Europe. He’s currently working in his first solo album.

Santos Puertas senses that at some point in the conversation he is going to be asked:

-Where are you from? Why do you speak with an accent? …

Santos is the perfect example that the music chooses you, you don’t choose the music.

When one listens to Santos Puertas singing and playing american music, it’s hard to believe that he was born in a small town called Sant Just Desvern, on the outskirts of Barcelona, Spain.

Singing came naturally to him from an early age.It is in his blood. His grandfather and his mother were gifted singers. Santos remembers that they use to sing around the house and at every celebration. Guitar is the instrument Santos chose to accompany his voice.

The story of Santos Puertas (formerly known as Pere Puertas) is a story full of effort, passion and determination. At the age of 16, Santos was loading and unloading trucks to make enough money to pay for his first electric guitar and a little amp.

When he was 18, he worked in a factory, and with the money he earned he went to London, UK. He lived there for a year working as a dishwasher and a waiter during the day and playing guitar at night.

He started his first blues band when he was 19, soon after he came back from England to his home town, and started teaching English lessons for the first time.

When he dropped out of his last year of college at 23, he focused on earning a living and playing music.

He was a substitute teacher at the American school in Barcelona and taught English in Spanish schools.Soon he would start getting paid to play gigs too.

In the year 2000 Santos crossed the pond for the first time and went to Austin, TX. He made a bunch of musician friends and felt very welcome in the blues scene. The same year, together with his brother Victor Puertas, harmonica virtuoso and gifted musician, started the great piedmont blues americana duo called ‘The

Suitcase Brothers’. Also in the year 2000 they cut their first record, ‘Living with the Blues’. Some of Santos’ students are featured in that first recording singing the song ‘Down by the Riverside’.

After playing together for 15 years, 4 recordings, 2 movie soundtracks and hundreds of gigs and venues, the duo has become an important reference in the blues scene in Spain and Europe. They also love to play with a rhythm section when they can. They participated at the IBC (International Blues Challenge) 2013 in Memphis, and ended up winning 2nd place among 100 others international blues acts. They started touring and making U.S. fans.

They have recently released their 4th album, named ‘A Long Way from Home’, recorded in Austin, Texas, which features friend and blues harmonica legend Jerry Portnoy, among others. This last recording has garnered a number of great reviews in Europe and the US and it was among the five finalists for the ‘Best Self Produced CD’ category at the IBC in 2015.

After the first trip to Austin, TX in 2000, Santos continued going back until in the summer of 2003, when he joined the soul singer Miss Lavelle White’s band and toured with her in Texas.

He has also been deeply involved in the blues scene in Barcelona, doing all sorts of collaborations such as: translating the late John Cephas and James Harman workshops, teaching blues guitar, and conducting a blues radio show called ‘Just Blues’ in his hometown for 2 years.

Santos has opened and/or jamed with many blues artists such as: Hubert Sumlin, Bob Margolin, Hook Herrera, Steve James, Gary Primich, Nick Curran, John Cephas & Phil Wiggins, Paul Rishell & Annie Raines, and Hash Brown, among many others Santos has recorded and/or played with Jerry Portnoy, Paul Oscher, Miss Lavelle White, Joel Foy, Christian Dozzler, Fred Kaplan, Mike Morgan, and Nathan James, among others.

For more than twenty years Santos has dedicated his talent to play Americana, blues, and roots music and has become a respected player and stellar performer. He moved to Dallas, TX in 2012 where he lives, performs and teaches when he is not touring in Europe. He’s currently working in his first solo album.

At the end of the second set a fan approaches Santos and starts a conversation.

Santos Puertas senses that at some point in the conversation he is going to be asked:

-Where are you from? Why

do you speak with an accent? …

Santos is the perfect example that the music chooses you, you don’t choose the music.

When one listens to Santos Puertas singing and playing american music, it’s hard to believe that he was born in a small town called Sant Just Desvern, on the outskirts of Barcelona, Spain.

Singing came naturally to him from an early age.It is in his blood. His grandfather and his mother were gifted singers. Santos remembers that they use to sing around the house and at every celebration. Guitar is the instrument Santos chose to accompany his voice.

The story of Santos Puertas (formerly known as Pere Puertas) is a story full of effort, passion and determination. At the age of 16, Santos was loading and unloading trucks to make enough money to pay for his first electric guitar and a little amp.

When he was 18, he worked in a factory, and with the money he earned he went to London, UK. He lived there for a year working as a dishwasher and a waiter during the day and playing guitar at night.

He started his first blues band when he was 19, soon after he came back from England to his home town, and started teaching English lessons for the first time.

When he dropped out of

his last year of college at 23, he focused on earning a living and playing music.

He was a substitute teacher at the Americ

an school in Barcelona and taught English in Spanish schools.Soon he would start getting paid to play gigs too.

In the year 2000 Santos crossed the pond for the first time and went to Austin, TX. He made a bunch of musician friends and felt very welcome in the blues scene. The same year, together with his brother Victor Puertas, harmonica virtuoso and gifted musician, started the great piedmont blues americana duo called ‘The

Suitcase Brothers’. Also in the year 2000 they cut their first record, ‘Living with the Blues’. Some of Santos’ students are featured in that first recording singing the song ‘Down by the Riverside’.

After playing together for 15 years, 4 recordings, 2 movie soundtracks and hundreds of gigs and venues, the duo has become an important reference in the blues scene in Spain and Europe. They also love to play with a rhythm section when they can. They participated at the IBC (International Blues Challenge) 2013 in Memphis, and ended up winning 2nd place among 100 others international blues acts. They started touring and making U.S. fans.

They have recently released their 4th album, named ‘A Long Way from Home’, recorded in Austin, Texas, which features friend and blues harmonica legend Jerry Portnoy, among others. This last recording has garnered a number of great reviews in Europe and the US and it was among the five finalists for the ‘Best Self Produced CD’ category at the IBC in 2015.

After the first trip to Austin, TX in 2000, Santos continued going back until in the summer of 2003, when he joined the soul singer Miss Lavelle White’s band and toured with her in Texas.

He has also been deeply involved in the blues scene in Barcelona, doing all sorts of collaborations such as: translating the late John Cephas and James Harman workshops, teaching blues guitar, and conducting a blues radio show called ‘Just Blues’ in his hometown for 2 years.

Santos has opened and/or jamed with many blues artists such as: Hubert Sumlin, Bob Margolin, Hook Herrera, Steve James, Gary Primich, Nick Curran, John Cephas & Phil Wiggins, Paul Rishell & Annie Raines, and Hash Brown, among many others Santos has recorded and/or played with Jerry Portnoy, Paul Oscher, Miss Lavelle White, Joel Foy, Christian Dozzler, Fred Kaplan, Mike Morgan, and Nathan James, among others.

For more than twenty years Santos has dedicated his talent to play Americana, blues, and roots music and has become a respected player and stellar performer. He moved to Dallas, TX in 2012 where he lives, performs and teaches when he is not touring in Europe. He’s currently working in his first solo album.

Santos Puertas senses that at some point in the conversation he is going to be asked:

-Where are you from? Why

do you speak with an accent? …

Santos is the perfect example that the music chooses you, you don’t choose the music.

When one listens to Santos Puertas singing and playing american music, it’s hard to believe that he was born in a small town called Sant Just Desvern, on the outskirts of Barcelona, Spain.

Singing came naturally to him from an early age.It is in his blood. His grandfather and his mother were gifted singers. Santos remembers that they use to sing around the house and at every celebration. Guitar is the instrument Santos chose to accompany his voice.

The story of Santos Puertas (formerly known as Pere Puertas) is a story full of effort, passion and determination. At the age of 16, Santos was loading and unloading trucks to make enough money to pay for his first electric guitar and a little amp.

When he was 18, he worked in a factory, and with the money he earned he went to London, UK. He lived there for a year working as a dishwasher and a waiter during the day and playing guitar at night.

He started his first blues band when he was 19, soon after he came back from England to his home town, and started teaching English lessons for the first time.

When he dropped out of

his last year of college at 23, he focused on earning a living and playing music.

He was a substitute teacher at the Americ

an school in Barcelona and taught English in Spanish schools.Soon he would start getting paid to play gigs too.

In the year 2000 Santos crossed the pond for the first time and went to Austin, TX. He made a bunch of musician friends and felt very welcome in the blues scene. The same year, together with his brother Victor Puertas, harmonica virtuoso and gifted musician, started the great piedmont blues americana duo called ‘The

Suitcase Brothers’. Also in the year 2000 they cut their first record, ‘Living with the Blues’. Some of Santos’ students are featured in that first recording singing the song ‘Down by the Riverside’.

After playing together for 15 years, 4 recordings, 2 movie soundtracks and hundreds of gigs and venues, the duo has become an important reference in the blues scene in Spain and Europe. They also love to play with a rhythm section when they can. They participated at the IBC (International Blues Challenge) 2013 in Memphis, and ended up winning 2nd place among 100 others international blues acts. They started touring and making U.S. fans.

They have recently released their 4th album, named ‘A Long Way from Home’, recorded in Austin, Texas, which features friend and blues harmonica legend Jerry Portnoy, among others. This last recording has garnered a number of great reviews in Europe and the US and it was among the five finalists for the ‘Best Self Produced CD’ category at the IBC in 2015.

After the first trip to Austin, TX in 2000, Santos continued going back until in the summer of 2003, when he joined the soul singer Miss Lavelle White’s band and toured with her in Texas.

He has also been deeply involved in the blues scene in Barcelona, doing all sorts of collaborations such as: translating the late John Cephas and James Harman workshops, teaching blues guitar, and conducting a blues radio show called ‘Just Blues’ in his hometown for 2 years.

Santos has opened and/or jamed with many blues artists such as: Hubert Sumlin, Bob Margolin, Hook Herrera, Steve James, Gary Primich, Nick Curran, John Cephas & Phil Wiggins, Paul Rishell & Annie Raines, and Hash Brown, among many others Santos has recorded and/or played with Jerry Portnoy, Paul Oscher, Miss Lavelle White, Joel Foy, Christian Dozzler, Fred Kaplan, Mike Morgan, and Nathan James, among others.

For more than twenty years Santos has dedicated his talent to play Americana, blues, and roots music and has become a respected player and stellar performer. He moved to Dallas, TX in 2012 where he lives, performs and teaches when he is not touring in Europe. He’s currently working in his first solo album.

Santos Puertas (Festival Blues Barcelona 2014)

THE SUITCASE BROTHERS - European Blues Challenge 2011

Overton Vertis "O. V." Wright (October 9, 1939 – November 16, 1980)[1] was an American singer who is generally regarded as a blues artist by African American fans in the Deep South; he is also regarded as one of Southern soul's most authoritative and individual artists.[2] His best known songs include "That's How Strong My Love Is" (1964), "You're Gonna Make Me Cry" (1965), "Nucleus of Soul" (1968), "A Nickel and a Nail" (1971), "I Can't Take It" (1971) and "Ace of Spades" (1971).

Born in Lenow, Tennessee, Wright, as a youngster, began singing in the church. In 1956, while still in high school, he joined The Sunset Travelers as one of the lead singers for the gospel group.[3] He later fronted a gospel music group, the Harmony Echoes. It was during this time that he was discovered (along with James Carr) by Roosevelt Jamison a songwriter and manager. Their first pop recording in 1964 was "That's How Strong My Love Is," a ballad later covered by Otis Redding and the Rolling Stones. It was issued on Goldwax, the label Wright signed to after leaving his gospel career. It was later determined that Don Robey still had him under a recording contract, due to his gospel group having recorded for Peacock. After his contract was shifted to Don Robey's Back Beat label, further R&B hits followed. Working with record producer Willie Mitchell, success continued on songs including "Ace of Spades" and "A Nickel and a Nail".

Wright's hits were much more popular in the deep South. His biggest hits were "You're Gonna Make Me Cry" (R&B #6, 1965), "Eight Men, Four Women" (R&B #4, 1967) "Ace of Spades" (R&B #11, 1970), "A Nickel and a Nail" (R&B #19, 1971). The remainder of his 17 hits charted no higher than #20 on the R&B charts.

However, Wright was imprisoned for narcotics offenses during the mid-1970s, and, despite signing for Hi Records and releasing a series of recordings, his commercial success failed to recover after his release. A continuing drug problem weakened his health and he died from a heart attack, in Mobile, Alabama at age 41.[1]

Wright is among the most remembered voices of soul music, perhaps mostly for being sampled frequently in hip hop music. In 1996, his song, "Motherless Child" was sampled on the Ghostface Killah album Ironman on a song also called "Motherless Child." It and another Wright recording, "Let's Straighten It Out" have been published on Shaolin Soul, a compilation of tracks that have been sampled by the Wu Tang Clan and its members. "Let's Straighten It Out" was sampled in a Wu-Tang Clan song called "America" from the charity compilation album America Is Dying Slowly. "Ace of Spades" was sampled by Slim Thug and the Boss Hogg Outlawz on a song named "Recognize A Playa".

Wright has been a big influence on many Soul and Blues singers including Robert Cray,[4] Otis Clay,[5] Taj Mahal[6] as well as young Soul singer Reggie Sears[7] among many others.

Johnny Rawls joined Wright's backing band in the mid-1970s, and played together with Wright until the latter's death in 1980. The band then continued billed as the O.V. Wright Band for another 13 years, and toured and performed with other musicians over this time span. These included B.B. King, Little Milton, Bobby Bland, Little Johnny Taylor, and Blues Boy Willie.

O. V. Wright - Today I sing the blues

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen