1935 Earl Gaines*

1939 Ginger Baker*

1953 Lynwood Slim*

1953 Willie Love+

1958 Ken Leiboff*

1959 Blind Willie McTell+

2013 Fritz Rau+

2014 James Kinds+

Mel Melton*

Happy Birthday

Mel Melton *19.08.

A North Carolina native, Mel went to Lafayette, Louisiana in the summer of 1969 to visit a college friend and play a little music before going back to UNC. His plans changed when he became totally immersed in the rich culture and physical beauty of southwest Louisiana. He moved permanently to Lafayette at the end of the summer and began playing in a band he co-founded with Sonny Landreth, the Louisiana slide guitar-playing superstar.

Mel MeltonTo help support his new musical career, Mel took a series of jobs in the best Cajun restaurants in the city and discovered a new talent and another part of Cajun lifestyle, Louisiana cooking. Over the next few years he honed his musical and cooking skills, eventually becoming a well known Cajun chef. At the same time, he was becoming known as a singer and harmonica player specializing in a zydeco style of harp playing that has become his trademark.

Mel arrived in Austin, Texas in 1972 at the start of the Austin music scene. He took a job at a BBQ joint near Lake Travis as a dishwasher, but eventually moved up the ranks to cook. The restaurant happened to be a hang out for several European chefs who worked at the resorts situated on Lake Travis and Melton was offered a cook position at one of them. While there, he joined Austin’s Chef Association and after several years, became chef at the Tarry House, a private club frequented by many Texas luminaries such as Walter Cronkite, Tommy Lee Jones, Sissy Spacek, and many Texas politicians including the Governor, who held a weekly staff lunch at the club.

In the early 80’s Sonny and Mel formed the band “Bayou Rhythm”, adding C.J. Chenier to the lineup. The band headlined shows nationally and also opened shows for a number of legendary musicians including: Ray Charles, B.B. King, Dr. John, The Neville Brothers, Stevie Ray Vaughn, Dave Edmonds, and The Fabulous Thunderbirds.

During his time with Bayou Rhythm, Mel was challenged to a gumbo cook-off by Rockin’ Dopsie at the 1986 American Music Festival in Chicago. The event was so well received that Melton decided to always cook for the band’s gigs and his peerless Cajun cooking quickly become a signature twist to his shows.

In 1986, Melton left Bayou Rhythm and moved to Chicago to pursue a full time chef career. In his first month there he won the prestigious Grand Prize at the Rolls Royce-Krug Champagne Invitational Chef Competition. Melton opened two new restaurants while in Chicago, one of which was named as one of the top ten new restaurants in the area. He frequently did cooking demonstrations and prepared food for a variety of events, including The Chicago Jazz Festival, The American Cancer Society Ball, Mardi Gras at The Limelight Club, and many others. He also appeared on the local television program “Two on Two,” and several radio programs.

Mel MeltonThe year 1990 found Melton back in North Carolina, where he still continues to spread his interpretation of the food and music he grew to love down in the bayou country. Mel is back in the spotlight, cooking on stage with his band, The Wicked Mojos, as well as off-stage. He has served as executive chef and independent restaurant consultant to many of the Triangle’s most notable restaurants and food service organizations.

A frequent guest chef at the Southern Season Cooking School in Chapel Hill, NC, Mel is parlaying his unique cooking and musical innovation into a new restaurant venture. Scheduled to open in late fall, Papa Mojo’s Cajun Kitchen will blur the lines between food and entertainment, taste and sounds, visual and musical. The restaurant will feature Mel’s renowned cajun recipes, appearances with his own band, and other live cajun/zydeco musical acts from around the southeast.

In an attempt to describe the roots of his music and food, Mel recited all of the influences that came to him from his long stay in the Bayou State. “There’s zydeco of course, and Cajun and blues, and New Orleans jazz and funk. But as far as what we’re playing, I like to call it ‘Mojo Music.’ It’s a lot like the food. Down there everyone cooks, but they all have their own little way of stirring it up. When people leave one of our shows or my restaurant, I want them to feel like they’ve been down in the swamp at a big party and they’ve had a great time. That’s what it’s all about.”

http://www.papamojosroadhouse.com/papa-mojos-roadhouse-mel-melton.htm

Welcome, ladies and gentlemen, to Mel Melton & The Wicked Mojos, a smokin' Zydeco/Cajun flavored blues band out of North Carolina. For those not in the know, let's meet the guys up close and...

MEL MELTON, on what was intended to be a brief visit to Lafayette LA in the early '70s turned out to be a life-changing experience. There he met, played with and forged lasting relationships with Sonny Landreth and Cheniers Clifton, Cleveland and CJ. After a long stint with Bayou Rhythm, Mel took time off from the music rat-race to concentrate on a chef career (another facet developed and sharpened from the early Lafayette days). 1990 found him back in NC and back at music, having formed the first edition of The Wicked Mojos. In 2008 Mel opened a new hot Cajun restaurant called Papa Mojo's Roadhouse (www.papamojosroadhouse.com). For a more detailed bio on Mel, please feel free to visit www.melmelton.com.

MAX DRAKE has been playing in and recording with blues/R&B bands such as Arhoolie, The Excellos and the Ministers of Sinister since the '60s. More recently, he has lent his fiery fretwork to the late Skeeter Brandon and Big Bill Morganfield before joining forces with The Wicked Mojos in 2005. Max also performs with a stripped-down nasty blues/roots band known as The Buzzkillz (www.myspace.com/buzzkillzboogie).

T.A. JAMES, after a 3 year sabbatical (intracontinental freight relocation), hooked up with the Wicked Mojos at the very tail end of 2007. He logged much of 20 years as bassist and guitarist, having spent '95-'03 as the low-end kingpin for the Carey Bell Band. More bio info for T.A. can be found at www.myspace.com/tajames68.

KELLY PACE logged road and recording time with Skeeter Brandon and an earlier version of Mel Melton & The Wicked Mojos (Mojo Dream) as throne man, and has also been a longtime member of Blues World Order. Kelly rejoined forces with the 'Mojos in 2009.

Thanks for visiting, and come again!

MEL MELTON, on what was intended to be a brief visit to Lafayette LA in the early '70s turned out to be a life-changing experience. There he met, played with and forged lasting relationships with Sonny Landreth and Cheniers Clifton, Cleveland and CJ. After a long stint with Bayou Rhythm, Mel took time off from the music rat-race to concentrate on a chef career (another facet developed and sharpened from the early Lafayette days). 1990 found him back in NC and back at music, having formed the first edition of The Wicked Mojos. In 2008 Mel opened a new hot Cajun restaurant called Papa Mojo's Roadhouse (www.papamojosroadhouse.com). For a more detailed bio on Mel, please feel free to visit www.melmelton.com.

MAX DRAKE has been playing in and recording with blues/R&B bands such as Arhoolie, The Excellos and the Ministers of Sinister since the '60s. More recently, he has lent his fiery fretwork to the late Skeeter Brandon and Big Bill Morganfield before joining forces with The Wicked Mojos in 2005. Max also performs with a stripped-down nasty blues/roots band known as The Buzzkillz (www.myspace.com/buzzkillzboogie).

T.A. JAMES, after a 3 year sabbatical (intracontinental freight relocation), hooked up with the Wicked Mojos at the very tail end of 2007. He logged much of 20 years as bassist and guitarist, having spent '95-'03 as the low-end kingpin for the Carey Bell Band. More bio info for T.A. can be found at www.myspace.com/tajames68.

KELLY PACE logged road and recording time with Skeeter Brandon and an earlier version of Mel Melton & The Wicked Mojos (Mojo Dream) as throne man, and has also been a longtime member of Blues World Order. Kelly rejoined forces with the 'Mojos in 2009.

Thanks for visiting, and come again!

Lynwood Slim *19.08.1953

Lynwood Slim (born Richard Dennis Duran, August 19, 1953,[1] Los Angeles, California) is an American blues harmonica player and singer. Slim is best known as a singer in the style of smooth easy jazz/blues as well as his harmonica and flute playing.

Slim started playing the trumpet at age 12, and the harmonica when he was 15.[1] His early influences include Jimmy Reed, Little Walter and Big Walter Horton. He played the Los Angeles music scene then moved to Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1974. He became a major force on the music scene, winning awards for best blues band in 1986.

Slim moved to Amsterdam, the Netherlands in 1988, returned to Los Angeles later that same year. He started working with Junior Watson, as well as Hollywood Fats Band alumni Larry Taylor, Fred Kaplan and Richard Innes. He started playing the flute after listening to James Moody and Herbie Mann.

Recording credits include a number of solo albums as well as numerous as a guest performer, producer, engineer, arranger and songwriter. Slim is currently signed to Delta Groove, an independent record label based in Van Nuys, California. He has toured and recorded in the United States as well as Europe, South America and Australia.

Slim's health has been on the decline since early 2011. Initially he was diagnosed with hepatitis C, which he overcame, but the damage to his liver caused cirrhosis. In late 2011 Slim was given news that without a liver transplant he would only survive for two years.[2] Slim does not have health insurance and is accepting donations through his website.

Earl Gaines *19.08.1935

http://www.musicrow.com/2010/01/nashville-rb-star-earl-gaines-1935-2009/

Earl Gaines (August 19, 1935 – December 31, 2009)[3] was an American soul blues and electric blues singer.[2] Born in Decatur, Alabama, he sang lead vocals on the hit single "It's Love Baby (24 Hours a Day)", credited to Louis Brooks and his Hi-Toppers,[3] before undertaking a low-key solo career. In the latter capacity he had minor success with "The Best of Luck to You" (1966) and "Hymn Number 5" (1973). Noted as the best R&B singer from Nashville, Gaines was also known for his lengthy career.

After moving from his hometown in his teenage years, and relocating to Nashville, Tennessee, Gaines found employment as both a singer and occasional drummer. Via work he did for local songwriter, Ted Jarrett, Gaines moved from singing in clubs to meeting Louis Brooks. Brooks led the instrumental Hi-Toppers, who had a recording contract with the Excello label. Their subsequent joint recording, "It's Love Baby (24 Hours a Day)," peaked at #2 on the US R&B chart in 1955. It was Gaines biggest hit, but his name was not credited on the record.[2]

Breaking away from the confines of the group, Gaines became part of the 1955 R&B Caravan of Stars, with Bo Diddley, Big Joe Turner, and Etta James.[5] Their tour culminated with an appearance at New York's Carnegie Hall.[2] Without any tangible success, Gaines recorded for the Champion and Poncello labels for another few years, as well as joining Bill Doggett's band as lead vocalist. In 1963, he joined Bill "Hoss" Allen's repertoire of artists, and by 1966 had issued the album, The Best of Luck to You, seeing the title track reach the Top 40 in the US R&B chart. He appeared on the television program The !!!! Beat, and later released material for King and Sound Stage 7, including his cover version of "Hymn Number 5".[2] Recordings made between 1967 and 1973 for De Luxe were reissued in 1998.[4] On many of his De Luxe recordings in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Gaines was backed by Freddy Robinson's orchestra.[6]

In 1975, Gaines recorded "Drowning On Dry Land" for Ace, before leaving the music industry for almost a decade and a half, to work as a truck driver.[2][7] He finally re-emerged in 1989 with the album House Party.[4]

In the 1990s Gaines worked with Roscoe Shelton and Clifford Curry.[7] On Appaloosa Records, Gaines issued I Believe in Your Love (1995), and in 1997 he reunited with Curry and Shelton for a collaborative live album.[2] He released Everything’s Gonna Be Alright in 1998.[4] Gaines work was on the 2005 Grammy Award winning Night Train To Nashville: Music City Rhythm & Blues, 1945–1970, an exhibit at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum.[5] His own albums The Different Feelings of Blues and Soul (2005) and Nothin’ But the Blues (2008) followed, the latter released on the Ecko label.[4][7]

In late 2009 Gaines had to cancel a concert tour of Europe due to ill health,[5] and he died in Nashville on the last day of that year, at the age of 74.[3]

He is not to be confused with Steven Earl Gaines, a fellow American musician.

After moving from his hometown in his teenage years, and relocating to Nashville, Tennessee, Gaines found employment as both a singer and occasional drummer. Via work he did for local songwriter, Ted Jarrett, Gaines moved from singing in clubs to meeting Louis Brooks. Brooks led the instrumental Hi-Toppers, who had a recording contract with the Excello label. Their subsequent joint recording, "It's Love Baby (24 Hours a Day)," peaked at #2 on the US R&B chart in 1955. It was Gaines biggest hit, but his name was not credited on the record.[2]

Breaking away from the confines of the group, Gaines became part of the 1955 R&B Caravan of Stars, with Bo Diddley, Big Joe Turner, and Etta James.[5] Their tour culminated with an appearance at New York's Carnegie Hall.[2] Without any tangible success, Gaines recorded for the Champion and Poncello labels for another few years, as well as joining Bill Doggett's band as lead vocalist. In 1963, he joined Bill "Hoss" Allen's repertoire of artists, and by 1966 had issued the album, The Best of Luck to You, seeing the title track reach the Top 40 in the US R&B chart. He appeared on the television program The !!!! Beat, and later released material for King and Sound Stage 7, including his cover version of "Hymn Number 5".[2] Recordings made between 1967 and 1973 for De Luxe were reissued in 1998.[4] On many of his De Luxe recordings in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Gaines was backed by Freddy Robinson's orchestra.[6]

In 1975, Gaines recorded "Drowning On Dry Land" for Ace, before leaving the music industry for almost a decade and a half, to work as a truck driver.[2][7] He finally re-emerged in 1989 with the album House Party.[4]

In the 1990s Gaines worked with Roscoe Shelton and Clifford Curry.[7] On Appaloosa Records, Gaines issued I Believe in Your Love (1995), and in 1997 he reunited with Curry and Shelton for a collaborative live album.[2] He released Everything’s Gonna Be Alright in 1998.[4] Gaines work was on the 2005 Grammy Award winning Night Train To Nashville: Music City Rhythm & Blues, 1945–1970, an exhibit at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum.[5] His own albums The Different Feelings of Blues and Soul (2005) and Nothin’ But the Blues (2008) followed, the latter released on the Ecko label.[4][7]

In late 2009 Gaines had to cancel a concert tour of Europe due to ill health,[5] and he died in Nashville on the last day of that year, at the age of 74.[3]

He is not to be confused with Steven Earl Gaines, a fellow American musician.

Ginger Baker *19.08.1939

http://www.gingerbaker.com/archives/gingerbakerarchivehome.htm

Ginger Baker (* 19. August 1939 in Lewisham, London, eigentlich Peter Edward Baker) ist ein englischer Schlagzeuger. Den Spitznamen „Ginger“ trägt er wegen seiner roten Haare.

Ursprünglich Klavier- und Trompetenspieler, wechselte er als Schlagzeuger ab 1955 zu Terry Lightfoot und Mr. Acker Bilk und nahm Unterricht bei Phil Seamen.

Ende der 1950er Jahre lernte Baker Dick Heckstall-Smith und Alexis Korner kennen. 1962 ersetzte er Charlie Watts als Schlagzeuger in Alexis Korners Blues Incorporated. Dort traf er auf Jack Bruce, Dick Heckstall-Smith und Graham Bond, mit denen er kurze Zeit darauf die Graham Bond Organization gründete. Baker nahm mit dieser Formation zwei Langspielplatten auf und tourte intensiv in Großbritannien. Baker gestaltete außerdem die Plattencover und kümmerte sich um die finanzielle Seite der Gruppe. 1966 entstand auf seine Initiative die Gruppe Cream mit Eric Clapton an der Gitarre und Jack Bruce am Bass. In dieser Dreier-Formation, die in den späten 1960er Jahren als Supergroup galt, spielten erstmals in der Popgeschichte alle beteiligten Instrumente – Gitarre, Bass, Schlagzeug – gleichberechtigt nebeneinander bis dahin in der Popmusik nicht gekannte ausgedehnte Improvisationen.

Nach der Auflösung von Cream spielte Ginger Baker mit Eric Clapton, Steve Winwood und Ric Grech in der Gruppe Blind Faith, die sich jedoch im September 1969 nach der Veröffentlichung des Albums Blind Faith und einer anschließenden, sehr erfolgreichen Tournee wieder auflöste.

1970 hatte Baker seine eigene Gruppe Ginger Baker's Air Force, die jedoch schon im Frühjahr 1971 wieder aufgelöst wurde. Mitglieder waren u.a. Phil Seamen, Steve Winwood (org,voc), Graham Bond (org), Ric Grech (bg,vi), Denny Laine und Chris Wood. Mit dieser offenen Formation, in der zwei Schlagzeuger und ein Percussionist tätig waren, wandte sich Baker afrikanischen Einflüssen zu und verlegte auch seinen Wohnsitz nach Nigeria. Der Einfluss seiner engen Zusammenarbeit mit Fela Kuti und die Auseinandersetzung mit afrikanischen, aber auch arabischen Harmonien und Rhythmen wird in späteren Alben wie Middle Passage hörbar.

Nach Ginger Baker's Air Force arbeitete er mit den Brüdern Paul und Adrian Gurvitz zusammen. Mit der Baker Gurvitz Army entstanden drei Alben. In den folgenden Jahren entstanden diverse Jazzeinspielungen.

1980 gehörte Baker kurzzeitig zur Band Hawkwind, die er aber nach dem Album Levitation wieder verließ.

1990 trat Ginger Baker in die Rockgruppe Masters of Reality ein und spielte mit Chris Goss und Googe das Album Sunrise on the Sufferbus ein. 1993 verließ Baker die Masters, als sie im Vorprogramm der Rockgruppe Alice in Chains auftraten, und widmete sich wieder dem Polo und seiner Pferdezucht. Er tourte und nahm CDs auf mit dem Bassisten Jonas Hellborg und veröffentlichte ein Album mit dem All-Star-Powertrio BBM mit Jack Bruce und Gary Moore.

Im Mai 2005 kam es in der Londoner Royal Albert Hall zu einem lang erwünschten Wiederauftritt der Formation Cream, die in Originalbesetzung ihr ehemaliges Repertoire präsentierte. Die Reihe von Konzerten wurde für eine CD- und DVD-Veröffentlichung ausgewertet.

2011 ging er nach vielen Jahren wieder mit dem Bassisten Jonas Hellborg auf Tournee.

2012 kam der US-Kinofilm „Beware of Mr. Baker“ heraus, eine Musik-Biopic des US-Regisseurs Jay Bulger über das bewegte Leben von Ginger Baker.[2] Der 92-minütige Dokumentarfilm kam Ende 2013 über den Verleih NFP auch in die deutschen Filmkunst-Kinos.[3] 2014 ist der Schlagzeuger mit seiner Band Ginger Baker's Jazz Confusion auf Tour.

Schlagzeugspiel und Instrumente

Ginger Baker war einer derjenigen Schlagzeuger, die maßgeblich zur Verbreitung des Spielens mit zwei Bassdrums beitrugen. Zwar hatte Louie Bellson das Doppelbassspielen schon früher erfunden, allerdings wurde es erst durch Baker im populären Bereich richtig bekannt und fand viele Nachahmer. Heute gehört es nahezu zum Standard des Schlagzeugspielens, wobei allerdings meistens eine Doppelfußmaschine die zweite Bassdrum ersetzt.

Zum Doppelbassdrumspielen bedarf es dreier Pedale, daraus folgt ein stetes Wechseln des linken Fußes zwischen zwei Pedalen (Hi-Hat-Maschine und Fußmaschine für die linke Bassdrum).

In der Zeit von Cream bis zur Baker Gurvitz Army spielte Ginger Baker ein Schlagzeug der Firma Ludwig in der Farbe „Silver Sparkle“, heute ein begehrtes Vintage-Schlagzeug. Baker benutzte zwei Bassdrums, zwei Hängetoms und zwei Standtoms, was man als Doppelschlagzeug bezeichnet, weil es genau die doppelte Anzahl des seinerzeit eigentlich üblichen Drumsets darstellte.

Neben Snare und Hi Hat benutzte Baker auch noch sechs, anstelle der eigentlich üblichen zwei Becken. Für diese verwendete er allerdings lediglich drei Ständer, da er jeweils zwei Becken auf einem Ständer montierte. Zusätzlich hatte er ein kleines Splash-Becken und eine Kuhglocke montiert.

Das Schlagzeugsolo Toad aus dem Jahr 1966 (veröffentlicht auf dem Album Fresh Cream) zeigt Bakers Umgang mit diesem großen Schlagzeug.

Bei den Cream-Reunion-Konzerten im Jahr 2005 spielte er ein Schlagzeug des Herstellers Drum Workshop (DW Drums), mit gleicher Trommelanzahl, allerdings anderem Aufbau der Toms.

Ursprünglich Klavier- und Trompetenspieler, wechselte er als Schlagzeuger ab 1955 zu Terry Lightfoot und Mr. Acker Bilk und nahm Unterricht bei Phil Seamen.

Ende der 1950er Jahre lernte Baker Dick Heckstall-Smith und Alexis Korner kennen. 1962 ersetzte er Charlie Watts als Schlagzeuger in Alexis Korners Blues Incorporated. Dort traf er auf Jack Bruce, Dick Heckstall-Smith und Graham Bond, mit denen er kurze Zeit darauf die Graham Bond Organization gründete. Baker nahm mit dieser Formation zwei Langspielplatten auf und tourte intensiv in Großbritannien. Baker gestaltete außerdem die Plattencover und kümmerte sich um die finanzielle Seite der Gruppe. 1966 entstand auf seine Initiative die Gruppe Cream mit Eric Clapton an der Gitarre und Jack Bruce am Bass. In dieser Dreier-Formation, die in den späten 1960er Jahren als Supergroup galt, spielten erstmals in der Popgeschichte alle beteiligten Instrumente – Gitarre, Bass, Schlagzeug – gleichberechtigt nebeneinander bis dahin in der Popmusik nicht gekannte ausgedehnte Improvisationen.

Nach der Auflösung von Cream spielte Ginger Baker mit Eric Clapton, Steve Winwood und Ric Grech in der Gruppe Blind Faith, die sich jedoch im September 1969 nach der Veröffentlichung des Albums Blind Faith und einer anschließenden, sehr erfolgreichen Tournee wieder auflöste.

1970 hatte Baker seine eigene Gruppe Ginger Baker's Air Force, die jedoch schon im Frühjahr 1971 wieder aufgelöst wurde. Mitglieder waren u.a. Phil Seamen, Steve Winwood (org,voc), Graham Bond (org), Ric Grech (bg,vi), Denny Laine und Chris Wood. Mit dieser offenen Formation, in der zwei Schlagzeuger und ein Percussionist tätig waren, wandte sich Baker afrikanischen Einflüssen zu und verlegte auch seinen Wohnsitz nach Nigeria. Der Einfluss seiner engen Zusammenarbeit mit Fela Kuti und die Auseinandersetzung mit afrikanischen, aber auch arabischen Harmonien und Rhythmen wird in späteren Alben wie Middle Passage hörbar.

Nach Ginger Baker's Air Force arbeitete er mit den Brüdern Paul und Adrian Gurvitz zusammen. Mit der Baker Gurvitz Army entstanden drei Alben. In den folgenden Jahren entstanden diverse Jazzeinspielungen.

1980 gehörte Baker kurzzeitig zur Band Hawkwind, die er aber nach dem Album Levitation wieder verließ.

1990 trat Ginger Baker in die Rockgruppe Masters of Reality ein und spielte mit Chris Goss und Googe das Album Sunrise on the Sufferbus ein. 1993 verließ Baker die Masters, als sie im Vorprogramm der Rockgruppe Alice in Chains auftraten, und widmete sich wieder dem Polo und seiner Pferdezucht. Er tourte und nahm CDs auf mit dem Bassisten Jonas Hellborg und veröffentlichte ein Album mit dem All-Star-Powertrio BBM mit Jack Bruce und Gary Moore.

Im Mai 2005 kam es in der Londoner Royal Albert Hall zu einem lang erwünschten Wiederauftritt der Formation Cream, die in Originalbesetzung ihr ehemaliges Repertoire präsentierte. Die Reihe von Konzerten wurde für eine CD- und DVD-Veröffentlichung ausgewertet.

2011 ging er nach vielen Jahren wieder mit dem Bassisten Jonas Hellborg auf Tournee.

2012 kam der US-Kinofilm „Beware of Mr. Baker“ heraus, eine Musik-Biopic des US-Regisseurs Jay Bulger über das bewegte Leben von Ginger Baker.[2] Der 92-minütige Dokumentarfilm kam Ende 2013 über den Verleih NFP auch in die deutschen Filmkunst-Kinos.[3] 2014 ist der Schlagzeuger mit seiner Band Ginger Baker's Jazz Confusion auf Tour.

Schlagzeugspiel und Instrumente

Ginger Baker war einer derjenigen Schlagzeuger, die maßgeblich zur Verbreitung des Spielens mit zwei Bassdrums beitrugen. Zwar hatte Louie Bellson das Doppelbassspielen schon früher erfunden, allerdings wurde es erst durch Baker im populären Bereich richtig bekannt und fand viele Nachahmer. Heute gehört es nahezu zum Standard des Schlagzeugspielens, wobei allerdings meistens eine Doppelfußmaschine die zweite Bassdrum ersetzt.

Zum Doppelbassdrumspielen bedarf es dreier Pedale, daraus folgt ein stetes Wechseln des linken Fußes zwischen zwei Pedalen (Hi-Hat-Maschine und Fußmaschine für die linke Bassdrum).

In der Zeit von Cream bis zur Baker Gurvitz Army spielte Ginger Baker ein Schlagzeug der Firma Ludwig in der Farbe „Silver Sparkle“, heute ein begehrtes Vintage-Schlagzeug. Baker benutzte zwei Bassdrums, zwei Hängetoms und zwei Standtoms, was man als Doppelschlagzeug bezeichnet, weil es genau die doppelte Anzahl des seinerzeit eigentlich üblichen Drumsets darstellte.

Neben Snare und Hi Hat benutzte Baker auch noch sechs, anstelle der eigentlich üblichen zwei Becken. Für diese verwendete er allerdings lediglich drei Ständer, da er jeweils zwei Becken auf einem Ständer montierte. Zusätzlich hatte er ein kleines Splash-Becken und eine Kuhglocke montiert.

Das Schlagzeugsolo Toad aus dem Jahr 1966 (veröffentlicht auf dem Album Fresh Cream) zeigt Bakers Umgang mit diesem großen Schlagzeug.

Bei den Cream-Reunion-Konzerten im Jahr 2005 spielte er ein Schlagzeug des Herstellers Drum Workshop (DW Drums), mit gleicher Trommelanzahl, allerdings anderem Aufbau der Toms.

Peter Edward "Ginger" Baker (born 19 August 1939) is an English drummer, best known as the founder of the rock band Cream.[1] Baker's work in the 1960s earned him praise as "rock's first superstar drummer", although his individual style melded a jazz background with his personal interest in African rhythms. Baker is an inductee of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of Cream and is widely considered one of the most influential drummers of all time.

Baker began playing drums at age 15, and later took lessons from Phil Seamen. In the 1960s, he joined Blues Incorporated, where he met the late bassist Jack Bruce. The two clashed often, but would be rhythm section partners again in The Graham Bond Organisation and Cream, the latter of which Baker co-founded with Eric Clapton in 1966. Cream achieved worldwide success but lasted just two years, in part due to Baker's and Bruce's volatile relationship. After briefly working with Clapton in Blind Faith and leading Ginger Baker's Air Force, Baker spent several years in the 1970s living and recording in Africa, often with Fela Kuti, in pursuit of his long-time interest in African music. Among Baker's other collaborations are his work with Gary Moore, Masters of Reality and Public Image Ltd, Atomic Rooster, Bill Laswell, jazz bassist Charlie Haden, jazz guitarist Bill Frisell, and another personally led effort, Ginger Baker's Energy.

Baker's drumming attracted attention for his style, showmanship, and use of two bass drums instead of the conventional one. In his early days, he performed lengthy drum solos, the best known being the five-minute solo from the Cream song "Toad", one of the earliest recorded examples in rock music. Baker is noted for his eccentric, often self-destructive lifestyle; he struggled with heroin addiction for many years, moved around the world often after making enemies, and has been beset with financial and tax troubles, partially as a result of his polo hobby. He has been married four times and has fathered three children.

Biography

Early life and career

Baker was born in Lewisham, South London. His mother worked in a tobacco shop; his father, Frederick Louvain Formidable Baker, was a bricklayer and Lance Corporal in the Royal Corps of Signals in WWII who died in the 1943 Dodecanese Campaign.[2]

An athletic child, Baker began playing drums at about 15 years old. In the early 1960s he took lessons from Phil Seamen, one of the leading British jazz drummers of the post-war era. He gained early fame as a member of The Graham Bond Organisation with future Cream bandmate Jack Bruce. The Graham Bond Organisation was an R&B/blues group with strong jazz leanings, .

Cream

Baker founded the rock band Cream in 1966 with Bruce and guitarist Eric Clapton. An innovative and fusion of blues, psychedelic rock and hard rock, the band released four albums in a little over two years before breaking up in 1968.[3]

Blind Faith

Baker then joined the short-lived "supergroup" Blind Faith, composed of Clapton, bassist Ric Grech, and Stevie Winwood on vocals. They released one album.

Ginger Baker's Air Force

In 1970 Baker formed, toured and recorded with fusion rock group Ginger Baker's Air Force.

1970s

Baker lived in Nigeria from 1970 until 1976.[4] He sat in for Fela Kuti[5] during recording sessions in 1971 released by Regal Zonophone as Live! (1971)'[6] Fela also appeared with Ginger Baker on Stratavarious (1972) alongside Bobby Gass,[7] a pseudonym for Bobby Tench[1] from The Jeff Beck Group. Stratavarious was later re-issued as part of the compilation Do What You Like.[8] Baker formed Baker Gurvitz Army in 1974 and recorded three albums with them before the band broke up in 1976.

1980s and '90s

In the early 1980s, Baker joined Hawkwind for an album and tour, and in the mid-1980s was part of John Lydon's Public Image Ltd., the latter leading to occasional collaborations with bassist/producer Bill Laswell.

In 1992 Baker played with the hard-rock group Masters of Reality with bassist Googe and singer/guitarist Chris Goss on the album Sunrise on the Sufferbus. The album received critical acclaim but sold fewer than 10,000 copies.

Baker lived in Parker, Colorado, a rural suburb of Denver, between 1993 and 1999, in part due to his passion for polo. Baker not only participated in polo events at the Salisbury Equestrian Park, but he also sponsored an ongoing series of jam sessions and concerts at the equestrian centre on weekends.[9]

In 1994 he formed The Ginger Baker Trio with bassist Charlie Haden and guitarist Bill Frisell. He also joined BBM, a short-lived power trio with the line-up of Baker, Jack Bruce and Irish blues rock guitarist Gary Moore.

2000s

On 3 May 2005, Baker reunited with Eric Clapton and Bruce for a series of Cream concerts at the Royal Albert Hall and Madison Square Garden. The London concerts were recorded and released as Royal Albert Hall London May 2–3–5–6 2005 (2005),[10] In a Rolling Stone article written in 2009, Bruce is quoted as saying: "It's a knife-edge thing between me and Ginger. Nowadays, we're happily co-existing in different continents [Bruce lives in Britain, Baker in South Africa] ... although I was thinking of asking him to move. He's still a bit too close".[11]

In 2008 a bank clerk, Lindiwe Noko, was charged with defrauding him of almost half a million Rand ($60,000).[12] The bank clerk claimed that it was a gift after she and Baker became lovers. Not so, insisted Baker, who explained, "I've a scar that only a woman who had a thing with me would know. It's there and she doesn't know it's there".[13] Noko was convicted of fraud and in October 2010 was sentenced to three years "correctional supervision" (a type of community service).[14]

Baker's autobiography Hellraiser was published in 2009.[1]

Baker has Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a lung disease.

In 2013 and 2014 Baker toured with the Ginger Baker Jazz Confusion, a quartet comprising Baker, saxophonist Pee Wee Ellis, bassist Alec Dankworth and percussionist Abass Dodoo.[15]

In 2014 Baker signed with record label Motéma Music to release a new jazz album. The album will feature members of the aforementioned quartet.[16]

Documentaries

In 2012, the documentary film Beware of Mr. Baker of Ginger Baker's life by Jay Bulger had its world premiere at South By Southwest in Austin, Texas where it won the grand jury award for best documentary feature. It received its UK premiere on BBC One on 7 July 2015[17][18] as part of the channel's Imagine series.

Ginger Baker in Africa (1971) documents Baker's drive from Algeria to Nigeria (across the Sahara desert by Range Rover), where in the capital, Lagos, he sets up a recording studio and jams with Fela Kuti.

Style

Baker cited Phil Seamen, Art Blakey, Max Roach, Elvin Jones, Philly Joe Jones and Baby Dodds as influences on his style.[19]

His drumming attracted attention for its flamboyance, showmanship and his use of two bass drums instead of the conventional single one (following a similar set-up used by Louie Bellson during his days with Duke Ellington). Although a firmly established rock drummer and praised as "Rock's first superstar drummer",[20] he prefers being called a jazz drummer.[21]

While at times performing similarly to Keith Moon from The Who, Baker also employs a more restrained style influenced by the British jazz groups he heard during the late 1950s and early 1960s. In his early days as a drummer, he performed lengthy drum solos, the best known being the five-minute drum solo "Toad" from Cream's debut album Fresh Cream (1966). He is also noted for using a variety of other percussion instruments and his application of African rhythms. He would often emphasise the flam, a drum rudiment in which both sticks attack the drumhead at almost the same time, giving a heavy thunderous sound.

Legacy

Baker's style influenced many drummers, including John Bonham,[22] Peter Criss,[23] Neil Peart,[24] Stewart Copeland,[25] Ian Paice,[26] Terry Bozzio,[27] Tommy Aldridge,[28] Bill Bruford,[29] Alex Van Halen,[30] Danny Seraphine[31] and Nick Mason.[32]

AllMusic has described him as "the most influential percussionist of the 1960s" and stated that "virtually every drummer of every heavy metal band that has followed since that time has sought to emulate some aspect of Baker's playing".[20] Modern Drummer magazine has described him as "one of classic rock's first influential drumming superstars of the 1960s" and "one of classic rock's true drum gods".[33]

DRUM! Magazine listed Baker among the "50 Most Important Drummers of All Time" and has defined him as "one of the most imitated '60s drummers",[34] stating also that "he forever changed the face of rock music".[35] He was voted the ninth greatest drummer of all time in a Rolling Stone reader poll and has been considered the "drummer who practically invented the rock drum solo".[36] According to writer Ken Micalief in his book Classic Rock Drummers: "the pantheon of contemporary drummers from metal, fusion, and rock owe their very existence to Baker's trailblazing work with Cream".[37]

Neil Peart has said: "His playing was revolutionary – extrovert, primal and inventive. He set the bar for what rock drumming could be. [...] Every rock drummer since has been influenced in some way by Ginger – even if they don't know it".

Baker began playing drums at age 15, and later took lessons from Phil Seamen. In the 1960s, he joined Blues Incorporated, where he met the late bassist Jack Bruce. The two clashed often, but would be rhythm section partners again in The Graham Bond Organisation and Cream, the latter of which Baker co-founded with Eric Clapton in 1966. Cream achieved worldwide success but lasted just two years, in part due to Baker's and Bruce's volatile relationship. After briefly working with Clapton in Blind Faith and leading Ginger Baker's Air Force, Baker spent several years in the 1970s living and recording in Africa, often with Fela Kuti, in pursuit of his long-time interest in African music. Among Baker's other collaborations are his work with Gary Moore, Masters of Reality and Public Image Ltd, Atomic Rooster, Bill Laswell, jazz bassist Charlie Haden, jazz guitarist Bill Frisell, and another personally led effort, Ginger Baker's Energy.

Baker's drumming attracted attention for his style, showmanship, and use of two bass drums instead of the conventional one. In his early days, he performed lengthy drum solos, the best known being the five-minute solo from the Cream song "Toad", one of the earliest recorded examples in rock music. Baker is noted for his eccentric, often self-destructive lifestyle; he struggled with heroin addiction for many years, moved around the world often after making enemies, and has been beset with financial and tax troubles, partially as a result of his polo hobby. He has been married four times and has fathered three children.

Biography

Early life and career

Baker was born in Lewisham, South London. His mother worked in a tobacco shop; his father, Frederick Louvain Formidable Baker, was a bricklayer and Lance Corporal in the Royal Corps of Signals in WWII who died in the 1943 Dodecanese Campaign.[2]

An athletic child, Baker began playing drums at about 15 years old. In the early 1960s he took lessons from Phil Seamen, one of the leading British jazz drummers of the post-war era. He gained early fame as a member of The Graham Bond Organisation with future Cream bandmate Jack Bruce. The Graham Bond Organisation was an R&B/blues group with strong jazz leanings, .

Cream

Baker founded the rock band Cream in 1966 with Bruce and guitarist Eric Clapton. An innovative and fusion of blues, psychedelic rock and hard rock, the band released four albums in a little over two years before breaking up in 1968.[3]

Blind Faith

Baker then joined the short-lived "supergroup" Blind Faith, composed of Clapton, bassist Ric Grech, and Stevie Winwood on vocals. They released one album.

Ginger Baker's Air Force

In 1970 Baker formed, toured and recorded with fusion rock group Ginger Baker's Air Force.

1970s

Baker lived in Nigeria from 1970 until 1976.[4] He sat in for Fela Kuti[5] during recording sessions in 1971 released by Regal Zonophone as Live! (1971)'[6] Fela also appeared with Ginger Baker on Stratavarious (1972) alongside Bobby Gass,[7] a pseudonym for Bobby Tench[1] from The Jeff Beck Group. Stratavarious was later re-issued as part of the compilation Do What You Like.[8] Baker formed Baker Gurvitz Army in 1974 and recorded three albums with them before the band broke up in 1976.

1980s and '90s

In the early 1980s, Baker joined Hawkwind for an album and tour, and in the mid-1980s was part of John Lydon's Public Image Ltd., the latter leading to occasional collaborations with bassist/producer Bill Laswell.

In 1992 Baker played with the hard-rock group Masters of Reality with bassist Googe and singer/guitarist Chris Goss on the album Sunrise on the Sufferbus. The album received critical acclaim but sold fewer than 10,000 copies.

Baker lived in Parker, Colorado, a rural suburb of Denver, between 1993 and 1999, in part due to his passion for polo. Baker not only participated in polo events at the Salisbury Equestrian Park, but he also sponsored an ongoing series of jam sessions and concerts at the equestrian centre on weekends.[9]

In 1994 he formed The Ginger Baker Trio with bassist Charlie Haden and guitarist Bill Frisell. He also joined BBM, a short-lived power trio with the line-up of Baker, Jack Bruce and Irish blues rock guitarist Gary Moore.

2000s

On 3 May 2005, Baker reunited with Eric Clapton and Bruce for a series of Cream concerts at the Royal Albert Hall and Madison Square Garden. The London concerts were recorded and released as Royal Albert Hall London May 2–3–5–6 2005 (2005),[10] In a Rolling Stone article written in 2009, Bruce is quoted as saying: "It's a knife-edge thing between me and Ginger. Nowadays, we're happily co-existing in different continents [Bruce lives in Britain, Baker in South Africa] ... although I was thinking of asking him to move. He's still a bit too close".[11]

In 2008 a bank clerk, Lindiwe Noko, was charged with defrauding him of almost half a million Rand ($60,000).[12] The bank clerk claimed that it was a gift after she and Baker became lovers. Not so, insisted Baker, who explained, "I've a scar that only a woman who had a thing with me would know. It's there and she doesn't know it's there".[13] Noko was convicted of fraud and in October 2010 was sentenced to three years "correctional supervision" (a type of community service).[14]

Baker's autobiography Hellraiser was published in 2009.[1]

Baker has Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a lung disease.

In 2013 and 2014 Baker toured with the Ginger Baker Jazz Confusion, a quartet comprising Baker, saxophonist Pee Wee Ellis, bassist Alec Dankworth and percussionist Abass Dodoo.[15]

In 2014 Baker signed with record label Motéma Music to release a new jazz album. The album will feature members of the aforementioned quartet.[16]

Documentaries

In 2012, the documentary film Beware of Mr. Baker of Ginger Baker's life by Jay Bulger had its world premiere at South By Southwest in Austin, Texas where it won the grand jury award for best documentary feature. It received its UK premiere on BBC One on 7 July 2015[17][18] as part of the channel's Imagine series.

Ginger Baker in Africa (1971) documents Baker's drive from Algeria to Nigeria (across the Sahara desert by Range Rover), where in the capital, Lagos, he sets up a recording studio and jams with Fela Kuti.

Style

Baker cited Phil Seamen, Art Blakey, Max Roach, Elvin Jones, Philly Joe Jones and Baby Dodds as influences on his style.[19]

His drumming attracted attention for its flamboyance, showmanship and his use of two bass drums instead of the conventional single one (following a similar set-up used by Louie Bellson during his days with Duke Ellington). Although a firmly established rock drummer and praised as "Rock's first superstar drummer",[20] he prefers being called a jazz drummer.[21]

While at times performing similarly to Keith Moon from The Who, Baker also employs a more restrained style influenced by the British jazz groups he heard during the late 1950s and early 1960s. In his early days as a drummer, he performed lengthy drum solos, the best known being the five-minute drum solo "Toad" from Cream's debut album Fresh Cream (1966). He is also noted for using a variety of other percussion instruments and his application of African rhythms. He would often emphasise the flam, a drum rudiment in which both sticks attack the drumhead at almost the same time, giving a heavy thunderous sound.

Legacy

Baker's style influenced many drummers, including John Bonham,[22] Peter Criss,[23] Neil Peart,[24] Stewart Copeland,[25] Ian Paice,[26] Terry Bozzio,[27] Tommy Aldridge,[28] Bill Bruford,[29] Alex Van Halen,[30] Danny Seraphine[31] and Nick Mason.[32]

AllMusic has described him as "the most influential percussionist of the 1960s" and stated that "virtually every drummer of every heavy metal band that has followed since that time has sought to emulate some aspect of Baker's playing".[20] Modern Drummer magazine has described him as "one of classic rock's first influential drumming superstars of the 1960s" and "one of classic rock's true drum gods".[33]

DRUM! Magazine listed Baker among the "50 Most Important Drummers of All Time" and has defined him as "one of the most imitated '60s drummers",[34] stating also that "he forever changed the face of rock music".[35] He was voted the ninth greatest drummer of all time in a Rolling Stone reader poll and has been considered the "drummer who practically invented the rock drum solo".[36] According to writer Ken Micalief in his book Classic Rock Drummers: "the pantheon of contemporary drummers from metal, fusion, and rock owe their very existence to Baker's trailblazing work with Cream".[37]

Neil Peart has said: "His playing was revolutionary – extrovert, primal and inventive. He set the bar for what rock drumming could be. [...] Every rock drummer since has been influenced in some way by Ginger – even if they don't know it".

Cream - Toad (Royal Albert Hall) (18 of 22)

Ken Leiboff *19.08.1958

http://worldofharmonica.blogspot.de/2011/05/ken-leiboff.html

https://www.facebook.com/kleiboff/about?section=overview&pnref=about

Ken Leiboff plays a "Hohner Harmonetta" - Vidéo web (YouTube)

R.I.P.

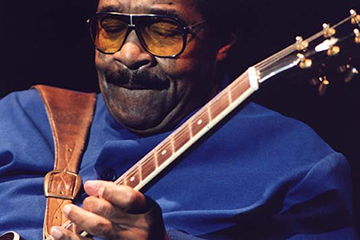

Blind Willie McTell +19.08.1959

Blind Willie McTell (* 5. Mai 1901 in Thomson, Georgia; † 19. August 1959 in Milledgeville, Georgia) (eigentlich William Samuel McTear) war ein einflussreicher US-amerikanischer Blues-Musiker und ein herausragender Repräsentant des Piedmont Blues.

In seiner frühen Kindheit komplett erblindet, war McTell aber in der Lage, mittels Braille-Musikschrift Noten zu lesen. 1934 heiratete er Ruth Kate Williams, mit der er bis zu seinem Tod verheiratet blieb. 1957 gab er den Blues auf und wandte sich der Religion zu, 1959 starb er an einer Hirnblutung. 1977 interviewte der Bluesforscher David Evans seine Witwe und förderte so erstmals Daten zu McTells Leben zutage.

Zu Lebzeiten war Blind Willie McTell kaum bekannt, trotzdem konnte er regelmäßig aufnehmen, indem er Agenten, die ihn ansprachen, jedes Mal ein anderes Pseudonym angab. So veröffentlichte er ab 1927 als „Blind Sammie“ für Columbia, „Georgia Bill“ für OKeh, als „Hot Shot Willie“ für Victor, als „Blind Willie“ für Vocalion und Bluebird, 1949 als „Barrelhouse Sammy“ für Atlantic und 1950 als „Pig n' Whistle Red“ für Regal. Trotz seiner relativ umfangreichen Diskographie lebte er hauptsächlich von seiner Tätigkeit als Straßenmusiker. Seine Musik ist ausgezeichnet durch seine klare Stimme und seine eigene Technik, 12-saitige Gitarren zu spielen.

Erst nach seinem Tod griffen viele andere Musiker, wie etwa die Allman Brothers, sein Werk auf, Bob Dylan schrieb 1983 das Lied Blind Willie McTell über ihn und coverte 1993 McTells Broke Down Engine.

McTell wurde 1981 in die Blues Hall of Fame aufgenommen.

In seiner frühen Kindheit komplett erblindet, war McTell aber in der Lage, mittels Braille-Musikschrift Noten zu lesen. 1934 heiratete er Ruth Kate Williams, mit der er bis zu seinem Tod verheiratet blieb. 1957 gab er den Blues auf und wandte sich der Religion zu, 1959 starb er an einer Hirnblutung. 1977 interviewte der Bluesforscher David Evans seine Witwe und förderte so erstmals Daten zu McTells Leben zutage.

Zu Lebzeiten war Blind Willie McTell kaum bekannt, trotzdem konnte er regelmäßig aufnehmen, indem er Agenten, die ihn ansprachen, jedes Mal ein anderes Pseudonym angab. So veröffentlichte er ab 1927 als „Blind Sammie“ für Columbia, „Georgia Bill“ für OKeh, als „Hot Shot Willie“ für Victor, als „Blind Willie“ für Vocalion und Bluebird, 1949 als „Barrelhouse Sammy“ für Atlantic und 1950 als „Pig n' Whistle Red“ für Regal. Trotz seiner relativ umfangreichen Diskographie lebte er hauptsächlich von seiner Tätigkeit als Straßenmusiker. Seine Musik ist ausgezeichnet durch seine klare Stimme und seine eigene Technik, 12-saitige Gitarren zu spielen.

Erst nach seinem Tod griffen viele andere Musiker, wie etwa die Allman Brothers, sein Werk auf, Bob Dylan schrieb 1983 das Lied Blind Willie McTell über ihn und coverte 1993 McTells Broke Down Engine.

McTell wurde 1981 in die Blues Hall of Fame aufgenommen.

Blind Willie McTell (born William Samuel McTier; May 5, 1898 – August 19, 1959) was a Piedmont and ragtime blues singer and guitarist. He played with a fluid, syncopated fingerstyle guitar technique, common among many exponents of Piedmont blues, although, unlike his contemporaries, he came to use twelve-string guitars exclusively. McTell was also an adept slide guitarist, unusual among ragtime bluesmen. His vocal style, a smooth and often laid-back tenor, differed greatly from many of the harsher voice types employed by Delta bluesmen, such as Charley Patton. McTell embodied a variety of musical styles, including blues, ragtime, religious music and hokum.

Born in the town of Thomson, Georgia, McTell learned how to play guitar in his early teens. He soon became a street performer around several Georgia cities including Atlanta and Augusta, and first recorded in 1927 for Victor Records. Although he never produced a major hit record, McTell's recording career was prolific, recording for different labels under different names throughout the 1920s and 30s. In 1940, he was recorded by folklorist John A. Lomax and Ruby Terrill Lomax for the Library of Congress's folk song archive. He would remain active throughout the 1940s and 50s, playing on the streets of Atlanta, often with his longtime associate, Curley Weaver. Twice more he recorded professionally. McTell's last recordings originated during an impromptu session recorded by an Atlanta record store owner in 1956. McTell would die three years later after suffering for years from diabetes and alcoholism. Despite his mainly failed releases, McTell was one of the few archaic blues musicians that would actively play and record during the 1940s and 50s. However, McTell never lived to be "rediscovered" during the imminent American folk music revival, as many other bluesmen would.[1]

McTell's influence extended over a wide variety of artists, including The Allman Brothers Band, who famously covered McTell's "Statesboro Blues", and Bob Dylan, who paid tribute to McTell in his 1983 song "Blind Willie McTell"; the refrain of which is, "And I know no one can sing the blues, like Blind Willie McTell". Other artists influenced by McTell include Taj Mahal, Alvin Youngblood Hart, Ralph McTell, Chris Smither and The White Stripes.

Biography

Born William Samuel McTier[2] in Thomson, Georgia, blind in one eye, McTell had lost his remaining vision by late childhood. He attended schools for the blind in the states of Georgia, New York and Michigan and showed proficiency in music from an early age, first playing harmonica and accordion, learning to read and write music in Braille,[1] and turning to the six-string guitar in his early teens.[1][2] His family background was rich in music, both of his parents and an uncle played guitar; he is also a relation of bluesman and gospel pioneer Thomas A. Dorsey.[2] His father left the family when McTell was still young, and, when his mother died in the 1920s, he left his hometown and became a wandering musician, or "songster". He began his recording career in 1927 for Victor Records in Atlanta.[3]

McTell married Ruth Kate Williams,[1] now better known as Kate McTell, in 1934. She accompanied him on stage and on several recordings before becoming a nurse in 1939. Most of their marriage from 1942 until his death was spent apart, with her living in Fort Gordon near Augusta and him working around Atlanta.

In the years before World War II, McTell traveled and performed widely, recording for a number of labels under many different names, including Blind Willie McTell (Victor and Decca), Blind Sammie (Columbia), Georgia Bill (Okeh), Hot Shot Willie (Victor), Blind Willie (Vocalion and Bluebird), Barrelhouse Sammie (Atlantic), and Pig & Whistle Red (Regal). The "Pig 'n Whistle" appellation was a reference to a chain of Atlanta barbecue restaurants, one of which was located on the south side of East Ponce de Leon between Boulevard and Moreland Avenue, which later became a Krispy Kreme. McTell would frequently played for tips in the parking lot of this location. He was also known to play behind the nearby building that later became Ray Lee's Blue Lantern Lounge. Like his fellow songster Lead Belly, who began his career as a street artist, McTell favored the somewhat unwieldy and unusual twelve-string guitar, whose greater volume made it suitable for outdoor playing.

In 1940 John A. Lomax and his wife, Ruby Terrill Lomax, Classics professor at the University of Texas at Austin, interviewed and recorded McTell for the Library of Congress's Folk Song Archive in a two-hour session held in their hotel room in Atlanta, Georgia. These recordings document McTell's distinctive musical style, which bridges the gap between the raw country blues of the early part of the 20th century and the more conventionally melodious, Ragtime-influenced East-Coast Piedmont blues sound. Mr. and Mrs. Lomax also elicited from the singer a number of traditional songs (such as "The Boll Weevil" and "John Henry") as well as spirituals (such as "Amazing Grace"), which were not part of his usual commercial repertoire. In the interview, John A. Lomax is heard asking if McTell knows any "complaining" songs (an earlier term for protest songs), to which the singer replies somewhat uncomfortably and evasively that he does not. The Library of Congress paid McTell $10, the equivalent of $154.56 in 2011, for this two-hour session.[3] The material from this 1940 session was issued in 1960 in LP and later in CD form, under the somewhat misleading title of "The Complete Library of Congress Recordings", notwithstanding the fact that it was in fact truncated, in that it omitted some of John A. Lomax's interactions with the singer and cut out entirely the contributions of Ruby Terrill Lomax.[4]

Postwar, McTell recorded for Atlantic Records and Regal Records in 1949, but these recordings met with less commercial success than his previous works. He continued to perform around Atlanta, but his career was cut short by ill health, predominantly diabetes and alcoholism. In 1956, an Atlanta record store manager, Edward Rhodes, discovered McTell playing in the street for quarters and enticed him with a bottle of corn liquor into his store, where he captured a few final performances on a tape recorder. These were released posthumously on Prestige/Bluesville Records as Last Session.[5] Beginning in 1957, McTell occupied himself as a preacher at Atlanta's Mt. Zion Baptist Church.[1]

McTell died in Milledgeville, Georgia, of a stroke in 1959. He was buried at Jones Grove Church, near Thomson, Georgia, his birthplace. A fan paid to have a gravestone erected on his resting place. The name given on his gravestone is Willie Samuel McTier.[6] He was inducted into the Blues Foundation's Hall of Fame in 1981,[7] and into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame in 1990.[1]

Influence

One of McTell's most famous songs, "Statesboro Blues," was frequently covered by The Allman Brothers Band and is considered one of their earliest signature songs[citation needed]. A short list of some of the artists who have performed it includes Taj Mahal, David Bromberg, Dave Van Ronk, The Devil Makes Three and Ralph McTell, who changed his name on account of liking the song.[8] Ry Cooder covered McTell's "Married Man's a Fool" on his 1973 album, Paradise and Lunch. Jack White of The White Stripes considers McTell an influence, as their 2000 album De Stijl was dedicated to him and featured a cover of his song "Southern Can Is Mine". The White Stripes also covered McTell's "Lord, Send Me an Angel", releasing it as a single in 2000. In 2013 Jack White's Third Man Records teamed up with Document Records to reissue The Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order of Charley Patton, Blind Willie McTell and The Mississippi Sheiks.

Bob Dylan has paid tribute to McTell on at least four occasions: Firstly, in his 1965 song "Highway 61 Revisited", the second verse begins with "Georgia Sam he had a bloody nose", referring to one of Blind Willie McTell's many recording names; later in his song "Blind Willie McTell", recorded in 1983 but released in 1991 on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3; then with covers of McTell's "Broke Down Engine" and "Delia" on his 1993 album, World Gone Wrong;[9] also, in his song "Po' Boy", on 2001's "Love & Theft", which contains the lyric, "had to go to Florida dodging them Georgia laws", which comes from McTell's "Kill It Kid".[10]

Also, Bath-based band "Kill It Kid" is named after that song.

A blues bar in Atlanta is named after McTell and regularly features blues musicians and bands.[11] The Blind Willie McTell Blues Festival is held annually in Thomson, Georgia.

Born in the town of Thomson, Georgia, McTell learned how to play guitar in his early teens. He soon became a street performer around several Georgia cities including Atlanta and Augusta, and first recorded in 1927 for Victor Records. Although he never produced a major hit record, McTell's recording career was prolific, recording for different labels under different names throughout the 1920s and 30s. In 1940, he was recorded by folklorist John A. Lomax and Ruby Terrill Lomax for the Library of Congress's folk song archive. He would remain active throughout the 1940s and 50s, playing on the streets of Atlanta, often with his longtime associate, Curley Weaver. Twice more he recorded professionally. McTell's last recordings originated during an impromptu session recorded by an Atlanta record store owner in 1956. McTell would die three years later after suffering for years from diabetes and alcoholism. Despite his mainly failed releases, McTell was one of the few archaic blues musicians that would actively play and record during the 1940s and 50s. However, McTell never lived to be "rediscovered" during the imminent American folk music revival, as many other bluesmen would.[1]

McTell's influence extended over a wide variety of artists, including The Allman Brothers Band, who famously covered McTell's "Statesboro Blues", and Bob Dylan, who paid tribute to McTell in his 1983 song "Blind Willie McTell"; the refrain of which is, "And I know no one can sing the blues, like Blind Willie McTell". Other artists influenced by McTell include Taj Mahal, Alvin Youngblood Hart, Ralph McTell, Chris Smither and The White Stripes.

Biography

Born William Samuel McTier[2] in Thomson, Georgia, blind in one eye, McTell had lost his remaining vision by late childhood. He attended schools for the blind in the states of Georgia, New York and Michigan and showed proficiency in music from an early age, first playing harmonica and accordion, learning to read and write music in Braille,[1] and turning to the six-string guitar in his early teens.[1][2] His family background was rich in music, both of his parents and an uncle played guitar; he is also a relation of bluesman and gospel pioneer Thomas A. Dorsey.[2] His father left the family when McTell was still young, and, when his mother died in the 1920s, he left his hometown and became a wandering musician, or "songster". He began his recording career in 1927 for Victor Records in Atlanta.[3]

McTell married Ruth Kate Williams,[1] now better known as Kate McTell, in 1934. She accompanied him on stage and on several recordings before becoming a nurse in 1939. Most of their marriage from 1942 until his death was spent apart, with her living in Fort Gordon near Augusta and him working around Atlanta.

In the years before World War II, McTell traveled and performed widely, recording for a number of labels under many different names, including Blind Willie McTell (Victor and Decca), Blind Sammie (Columbia), Georgia Bill (Okeh), Hot Shot Willie (Victor), Blind Willie (Vocalion and Bluebird), Barrelhouse Sammie (Atlantic), and Pig & Whistle Red (Regal). The "Pig 'n Whistle" appellation was a reference to a chain of Atlanta barbecue restaurants, one of which was located on the south side of East Ponce de Leon between Boulevard and Moreland Avenue, which later became a Krispy Kreme. McTell would frequently played for tips in the parking lot of this location. He was also known to play behind the nearby building that later became Ray Lee's Blue Lantern Lounge. Like his fellow songster Lead Belly, who began his career as a street artist, McTell favored the somewhat unwieldy and unusual twelve-string guitar, whose greater volume made it suitable for outdoor playing.

In 1940 John A. Lomax and his wife, Ruby Terrill Lomax, Classics professor at the University of Texas at Austin, interviewed and recorded McTell for the Library of Congress's Folk Song Archive in a two-hour session held in their hotel room in Atlanta, Georgia. These recordings document McTell's distinctive musical style, which bridges the gap between the raw country blues of the early part of the 20th century and the more conventionally melodious, Ragtime-influenced East-Coast Piedmont blues sound. Mr. and Mrs. Lomax also elicited from the singer a number of traditional songs (such as "The Boll Weevil" and "John Henry") as well as spirituals (such as "Amazing Grace"), which were not part of his usual commercial repertoire. In the interview, John A. Lomax is heard asking if McTell knows any "complaining" songs (an earlier term for protest songs), to which the singer replies somewhat uncomfortably and evasively that he does not. The Library of Congress paid McTell $10, the equivalent of $154.56 in 2011, for this two-hour session.[3] The material from this 1940 session was issued in 1960 in LP and later in CD form, under the somewhat misleading title of "The Complete Library of Congress Recordings", notwithstanding the fact that it was in fact truncated, in that it omitted some of John A. Lomax's interactions with the singer and cut out entirely the contributions of Ruby Terrill Lomax.[4]

Postwar, McTell recorded for Atlantic Records and Regal Records in 1949, but these recordings met with less commercial success than his previous works. He continued to perform around Atlanta, but his career was cut short by ill health, predominantly diabetes and alcoholism. In 1956, an Atlanta record store manager, Edward Rhodes, discovered McTell playing in the street for quarters and enticed him with a bottle of corn liquor into his store, where he captured a few final performances on a tape recorder. These were released posthumously on Prestige/Bluesville Records as Last Session.[5] Beginning in 1957, McTell occupied himself as a preacher at Atlanta's Mt. Zion Baptist Church.[1]

McTell died in Milledgeville, Georgia, of a stroke in 1959. He was buried at Jones Grove Church, near Thomson, Georgia, his birthplace. A fan paid to have a gravestone erected on his resting place. The name given on his gravestone is Willie Samuel McTier.[6] He was inducted into the Blues Foundation's Hall of Fame in 1981,[7] and into the Georgia Music Hall of Fame in 1990.[1]

Influence

One of McTell's most famous songs, "Statesboro Blues," was frequently covered by The Allman Brothers Band and is considered one of their earliest signature songs[citation needed]. A short list of some of the artists who have performed it includes Taj Mahal, David Bromberg, Dave Van Ronk, The Devil Makes Three and Ralph McTell, who changed his name on account of liking the song.[8] Ry Cooder covered McTell's "Married Man's a Fool" on his 1973 album, Paradise and Lunch. Jack White of The White Stripes considers McTell an influence, as their 2000 album De Stijl was dedicated to him and featured a cover of his song "Southern Can Is Mine". The White Stripes also covered McTell's "Lord, Send Me an Angel", releasing it as a single in 2000. In 2013 Jack White's Third Man Records teamed up with Document Records to reissue The Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order of Charley Patton, Blind Willie McTell and The Mississippi Sheiks.

Bob Dylan has paid tribute to McTell on at least four occasions: Firstly, in his 1965 song "Highway 61 Revisited", the second verse begins with "Georgia Sam he had a bloody nose", referring to one of Blind Willie McTell's many recording names; later in his song "Blind Willie McTell", recorded in 1983 but released in 1991 on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3; then with covers of McTell's "Broke Down Engine" and "Delia" on his 1993 album, World Gone Wrong;[9] also, in his song "Po' Boy", on 2001's "Love & Theft", which contains the lyric, "had to go to Florida dodging them Georgia laws", which comes from McTell's "Kill It Kid".[10]

Also, Bath-based band "Kill It Kid" is named after that song.

A blues bar in Atlanta is named after McTell and regularly features blues musicians and bands.[11] The Blind Willie McTell Blues Festival is held annually in Thomson, Georgia.

Blind Willie McTell - Searching The Desert For The Blues

Willie Love +19.08.1953

http://www.wirz.de/music/lovewfrm.htm

Willie Love (* 4. November 1906 in Duncan, Bolivar County, Mississippi; † 19. August 1953 in Jackson, Mississippi) war ein US-amerikanischer Bluespianist.

Der wichtigste Einfluss auf Loves Klavierstil war Leroy Carr.[1]1942 traf er in Greenville Sonny Boy Williamson II., wo sie gemeinsam auf der Nelson Street, dem Zentrum der schwarzen Community der Stadt, spielten. Williamson war es auch, der Love zu Trumpet Records mitnahm. Dort spielte Love bei den ersten Aufnahmen Klavier.

Zwischen 1951 und 1953 nahm Love bei Trumpet unter eigenem Namen Platten auf. Bei der Aufnahme von Everybody's Fishing, seinem erfolgreichsten Titel, spielte Elmore James die Gitarre. Bei späteren Aufnahmen spielte Little Milton. Seine letzte Aufnahmesession war im April 1953. Bei dieser Session spielte er mit einem weißen Bassisten, was zur damaligen Zeit in Mississippi, dem Staat mit der strengsten Segregation, eine Seltenheit war.[2] Im August 1953 starb er an den Folgen seiner langanhaltenden Trunksucht. Er liegt auf dem Elmwood Cemetery in Jackson begraben.

Auf der CD Greenville Smokin' wurden im Jahr 2000 die noch vorhandenen Aufnahmen Loves veröffentlicht.

Der wichtigste Einfluss auf Loves Klavierstil war Leroy Carr.[1]1942 traf er in Greenville Sonny Boy Williamson II., wo sie gemeinsam auf der Nelson Street, dem Zentrum der schwarzen Community der Stadt, spielten. Williamson war es auch, der Love zu Trumpet Records mitnahm. Dort spielte Love bei den ersten Aufnahmen Klavier.

Zwischen 1951 und 1953 nahm Love bei Trumpet unter eigenem Namen Platten auf. Bei der Aufnahme von Everybody's Fishing, seinem erfolgreichsten Titel, spielte Elmore James die Gitarre. Bei späteren Aufnahmen spielte Little Milton. Seine letzte Aufnahmesession war im April 1953. Bei dieser Session spielte er mit einem weißen Bassisten, was zur damaligen Zeit in Mississippi, dem Staat mit der strengsten Segregation, eine Seltenheit war.[2] Im August 1953 starb er an den Folgen seiner langanhaltenden Trunksucht. Er liegt auf dem Elmwood Cemetery in Jackson begraben.

Auf der CD Greenville Smokin' wurden im Jahr 2000 die noch vorhandenen Aufnahmen Loves veröffentlicht.

Willie Love (November 4, 1906 – August 19, 1953)[1] was an American Delta blues pianist. He is best known for his association with, and accompaniment of Sonny Boy Williamson II.

Biography

Love was born in Duncan, Mississippi, and in 1942, he met Sonny Boy Williamson II in Greenville, Mississippi.[2] They played regularly together at juke joints throughout the Mississippi Delta.[3] Love was influenced by the piano playing of Leroy Carr, and adept at both standard blues and boogie-woogie styling.[2]

In 1947 Charley Booker moved to Greenville, where he worked with Love.[4] Two years later, Oliver Sain also relocated to Greenville to join his stepfather, Love, as the drummer in a band fronted by Williamson. When Williamson recorded for Trumpet Records in March 1951, Love played the piano on the recordings. Trumpet's owner, Lillian McMurray, had Love return the following month, and again in July 1951, when Love recorded his best-known number, the self-penned, "Everybody's Fishing." Love played piano and sang, while the accompanying guitar come from Elmore James and Joe Willie Wilkins. His backing band was known as the Three Aces. A studio session in December 1951 had Love backed by Little Milton (guitar), T.J. Green (fiddle), and Junior Blackman (drums).[3] In his teenage years, Eddie Shaw played tenor saxophone with both Milton and Love.[5]

Under his own name, Love did not return to the studio until March 1953, when he cut "Worried Blues" and "Lonesome World Blues." Despite the friendship between them, Love did not utilise Williamson's playing on any of his own material.[2] In April 1953, Love and Williamson recorded in Houston, Texas, but it was Love's final recording session.[2][3]

Love played piano on Williamson's albums, I Ain't Beggin' Nobody and Clownin' With The World (1953).[3][6] All of Love's own recordings appeared on the compilation album, Greenville Smokin', issued in 2000.

After suffering the effects of years of heavy drinking,[3] Love died of bronchopneumonia, in August 1953, at the age of 46.[1] He was interred at the Elmwood Cemetery in Jackson, Mississippi.

Biography

Love was born in Duncan, Mississippi, and in 1942, he met Sonny Boy Williamson II in Greenville, Mississippi.[2] They played regularly together at juke joints throughout the Mississippi Delta.[3] Love was influenced by the piano playing of Leroy Carr, and adept at both standard blues and boogie-woogie styling.[2]

In 1947 Charley Booker moved to Greenville, where he worked with Love.[4] Two years later, Oliver Sain also relocated to Greenville to join his stepfather, Love, as the drummer in a band fronted by Williamson. When Williamson recorded for Trumpet Records in March 1951, Love played the piano on the recordings. Trumpet's owner, Lillian McMurray, had Love return the following month, and again in July 1951, when Love recorded his best-known number, the self-penned, "Everybody's Fishing." Love played piano and sang, while the accompanying guitar come from Elmore James and Joe Willie Wilkins. His backing band was known as the Three Aces. A studio session in December 1951 had Love backed by Little Milton (guitar), T.J. Green (fiddle), and Junior Blackman (drums).[3] In his teenage years, Eddie Shaw played tenor saxophone with both Milton and Love.[5]

Under his own name, Love did not return to the studio until March 1953, when he cut "Worried Blues" and "Lonesome World Blues." Despite the friendship between them, Love did not utilise Williamson's playing on any of his own material.[2] In April 1953, Love and Williamson recorded in Houston, Texas, but it was Love's final recording session.[2][3]

Love played piano on Williamson's albums, I Ain't Beggin' Nobody and Clownin' With The World (1953).[3][6] All of Love's own recordings appeared on the compilation album, Greenville Smokin', issued in 2000.

After suffering the effects of years of heavy drinking,[3] Love died of bronchopneumonia, in August 1953, at the age of 46.[1] He was interred at the Elmwood Cemetery in Jackson, Mississippi.

Willie Love, Little Car Blues

Fritz Rau +19.08.2013

Fritz

Rau (* 9. März 1930 in Pforzheim, Republik Baden; † 19. August 2013 in

Kronberg im Taunus, Hessen[1]) war ein deutscher Konzert- und

Tourneeveranstalter.

Fritz Rau wurde als Sohn eines Ittersbacher Schmieds in Pforzheim geboren. Seine Eltern verstarben früh, weshalb er ab 1940 bei Verwandten in Berlin aufgenommen wurde. Später besuchte er das Eichendorff-Gymnasium in Ettlingen, wo er auch Schülersprecher war, und studierte dann, gefördert von der Studienstiftung des Deutschen Volkes, Jura an der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg. Er beendete sein Studium mit dem Ersten Staatsexamen (am OLG Karlsruhe) und seine praktische Ausbildung als Gerichtsreferendar in Rheinland-Pfalz mit dem zweiten Staatsexamen beim Justizministerium Rheinland-Pfalz. Er war auch kurz als Rechtsanwalt in einer Kanzlei in Neustadt an der Weinstraße tätig.[2] Bereits im Studium engagierte er sich im Jazz-Club Cave 54 in Heidelberg. Noch als Student heiratete Rau und bekam mit seiner Frau zwei Kinder.[3]

Am 2. Dezember 1955 veranstaltete er sein erstes großes Konzert in der Heidelberger Stadthalle mit Albert Mangelsdorff, das mit 1.400 Besuchern weit über dem üblichen Publikumsinteresse bei deutschen Jazzclubs lag. Der Konzertagent und Jazz-Promoter Horst Lippmann wurde dadurch auf ihn aufmerksam und engagierte ihn als „Kofferträger“ für die Tournee-Reihe Jazz at the Philharmonic des US-amerikanischen Impresarios Norman Granz.[3] Neben seiner Ausbildung übte er weiterhin die Nebentätigkeit als Tourneeleiter aus. So wurde er der verantwortliche Konzertorganisator der Deutschen Jazz Föderation. 1963 bot ihm sein Freund Horst Lippmann eine Zusammenarbeit an und nahm ihn als Partner in seine Konzertagentur auf, die nun „Lippmann + Rau“ genannt wurde. Sie wurde durch die Organisation des American Folk Blues Festivals bekannt, auf denen die bisher nur in Insiderkreisen gefeierten Blues-Größen wie Willie Dixon und Howlin’ Wolf auftraten. Raus Aufgabe als Tourneeleiter bestand auch darin, die Bluesmusiker von hartem Alkohol fernzuhalten. Einigen Fans, die Whiskey einschmuggelten, erteilte er Hausverbot – Mick Jagger und Keith Richard, kurz bevor sie die Rolling Stones gründeten, sowie Robert Plant. Aus dem mit dem Festival geförderten Blues-Boom gingen in England Rockgruppen wie die Rolling Stones, die Yardbirds, Cream und viele andere hervor; die Tourneen der Rolling Stones wurden ab 1970 von Rau organisiert, der sich auch mit Jagger befreundete. Rau entwickelte neue Konzertformate und veranstaltete die ersten Open-Air-Rockkonzerte in Deutschland.

Gemeinsam mit Horst Lippmann hat Fritz Rau auch die Plattenlabels Scout und L+R (Lippmann + Rau) gegründet und betrieben. 1989 fusionierte „Lippmann + Rau“ mit der Agentur „Mama Concerts“ von Marcel Avram zu „Mama Concerts und Rau“. 1998 folgte die Ausgründung zur „Fritz Rau GmbH“. Seit 2001 arbeitete Rau als unabhängiger Produzent und Tourneeorganisator.

Rau arbeitete mit zahlreichen Musikgrößen der Pop-Kultur zusammen, darunter den Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, Joan Baez, Peter Maffay, Scorpions, Tina Turner, Michael Jackson, Charles Aznavour, Bob Dylan, Marlene Dietrich, Ella Fitzgerald, The Doors, The Les Humphries Singers, Miles Davis, Frank Zappa, Rory Gallagher, The Who, David Bowie, Freddie Mercury und Queen, Janis Joplin, Udo Lindenberg, Udo Jürgens, Gitte Hænning, Nana Mouskouri, Madonna, Prince, Eric Clapton, Rod Stewart, Simon & Garfunkel, Harry Belafonte, ABBA, Ton Steine Scherben bis hin zu Albert Mangelsdorff. Außerdem war er bis 2005 langjähriger Organisator von Jethro Tull und mit deren Bandleader Ian Anderson eng befreundet. Waren es anfänglich noch überwiegend Musiker der Jazz- und Bluesmusik, deren Tourneen er organisierte, verlagerte er mit dem Aufkommen der Hippie-Bewegung ähnlich wie der Musikproduzent Ertegün sein Interesse auf die Rock- und Popmusik. Raus tatkräftige, aufbrausende Art brachte ihm den Spitznamen „Ayatollah Choleri“ ein. Seine juristische Ausbildung war ihm bei geschäftlichen Konflikten ein hilfreiches Mittel, seine Interessen durchzusetzen.[3]

1983 unterstützte Rau, bewegt durch Petra Kelly, die junge Partei Die Grünen in ihrem Bundestagswahlkampf, indem er die Grüne Raupe organisierte. Hierbei handelte es sich um politische Veranstaltungen, bei denen grüne Redner Ansprachen hielten und Bands, die der Friedensbewegung nahestanden, unentgeltlich für den musikalischen Rahmen sorgten.

Einen Tag nach der Bundestagswahl 1983 trat Fritz Rau aus der Grünen-Partei aus. Der Konzertveranstalter vertrat später die Ansicht, dass „es nicht Aufgabe von Künstlern sein kann, ihre Popularität und ihr Können als sachfremdes Argument in den Wahlkampf einzubringen.“[4]

Als Madonna 1987 auf Europatournee ging und ihren einzigen Deutschlandauftritt im Frankfurter Waldstadion absolvierte, bot Rau als Veranstalter in gemeinsamer Planung mit der Deutschen Bundesbahn 20 Sonderzüge mit je 1000 Fahrplätzen an, die aus der ganzen Bundesrepublik zum Konzertort hin- und zurückfuhren. Diese Aktion lief unter dem Namen „Rock’n’Rail“, die Bahn schaltete dazu im Vorverkauf bundesweit eine ganzseitige Werbeanzeige in der Bild-Zeitung. Der Bahnhof Sportfeld in Frankfurt wurde vorübergehend in „Bahnhof Madonna“ umbenannt. Während der Fahrt wurde in jedem Zug unter den Mitreisenden eine „Miss Madonna“-Wahl abgehalten.

Fritz Rau förderte deutschsprachige Rockmusiker wie Udo Lindenberg oder Peter Maffay. Einer weiteren kommerziell erfolgreichen wie umstrittenen Rockgruppe mit deutschen Texten, den Böhsen Onkelz, verweigerte er jedoch die Zusammenarbeit. „Ich habe keine Lust, eine Tournee mit den Böhsen Onkelz durchzuführen, weil ich nicht der Meinung bin, dass sich die Böhsen Onkelz von ihrer Vergangenheit, die äußerst bedenklich ist, seit den früheren Platten vor acht bis zehn Jahren distanziert haben“, erklärte Fritz Rau in der Fernsehsendung ARD-Kulturreport am 31. Januar 1993.[5]

In seiner 2005 erschienenen Biographie 50 Jahre Backstage - Erinnerungen eines Konzertveranstalters zog er auf humorvolle Weise die Bilanz eines reichen und erfüllten Lebens. Das Buch ist seiner verstorbenen Frau Hildegard und seinem langjährigen Partner Horst Lippmann gewidmet.

Rau trat als Gastdozent an Musikhochschulen und Universitäten auf. Ab dem Sommersemester 2007 lehrte er als Honorarprofessor an der Hochschule für Musik und Darstellende Kunst Frankfurt am Main. Er lebte in einer Seniorenresidenz in Kronberg im Taunus.[6] Die Lippmann+Rau-Stiftung bewahrt mit dem Lippmann+Rau-Musikarchiv in Eisenach das Andenken an zwei verdiente Promoter.

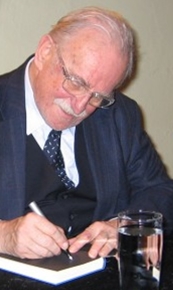

Fritz Rau (1984)

Anlässlich des 50-jährigen Jubiläums sowohl der American Folk Blues Festivals als auch der Rolling Stones im Jahr 2012 trat Rau zusammen mit dem Musiker Biber Herrmann mit einem aus Vortrag und Livemusik bestehenden Programm auf, das Anfang 2013 unter dem Titel Ein Plädoyer für den Blues auf einer Doppel-CD erschien. Im selben Jahr wurde er zusammen mit Horst Lippmann in die Blues Hall of Fame aufgenommen.

Rau litt an Diabetes.[7] Ein Herzinfarkt 1994 veranlasste ihn dazu, sich einer Bypass-Operation zu unterziehen. Seit einem Schlaganfall 1999 litt er an einem eingeschränkten Sehvermögen.

Zu dem Jazz-Pianisten Oscar Peterson pflegte Fritz Rau eine Freundschaft, weshalb Rau seinen 1958 geborenen Sohn Andreas Oscar nannte; zugleich war Peterson der Pate von Raus Sohn.

Zitate zu Fritz Rau

„Er ist wie ein Vater für mich.“[4] (Udo Lindenberg)

„He is everybody's Papa.“[8] (Al Jarreau)

„Fritz ist eine der legendären Figuren des deutschen Showbusiness. Ohne ihn hätte es diese großen Hallenkonzerttourneen mit vielen Künstlern nicht gegeben“[9] (Udo Jürgens)

„You are the godfather of us all. Rock’n’Rau Forever!“[3] (Mick Jagger)

„Er schläft nie. Er überlebt bei Bier, Schnitzeln und Gugelhupf.“[4] (Joan Baez)

„Fritz ist absolut raumfüllend. Fritz hat eine spontane herzliche Seite. Ich habe Fritz auch lautstark erlebt. Wenn er sich durchsetzen wollte, dann hat man ihn total wahrgenommen. Nicht nur argumentativ. Auch physisch. Wenn Fritz gegen eine Wand lief, dann wackelte die.“[10] (Peter Maffay)