1893 Coot Grant*, + unbekannt

1925 Peppermint Harris*

1939 Spencer Davis*

1940 Margie Evans*

1942 Zoot Money*

1947 Abraham „Abe“ Laboriel*

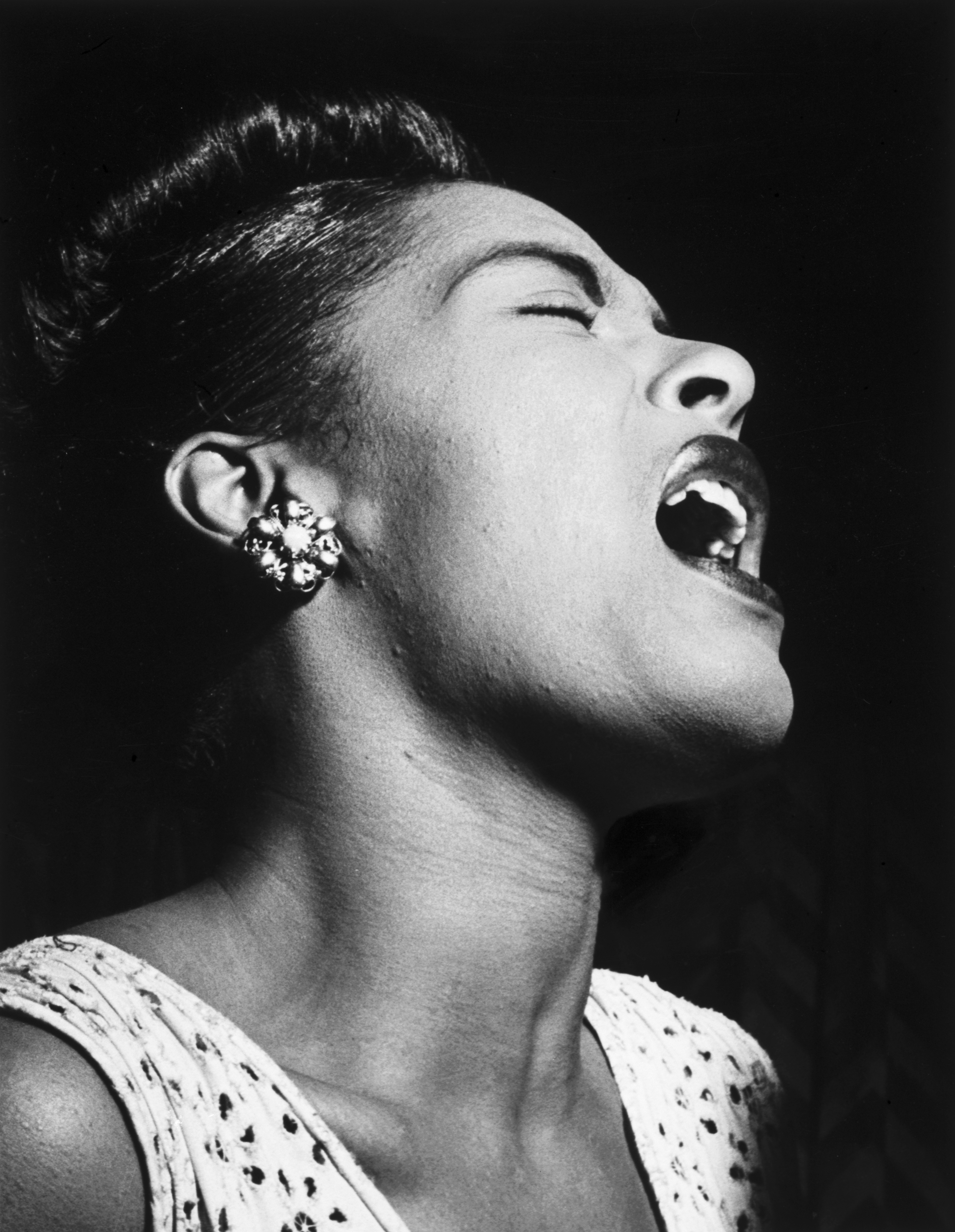

1959 Billie Holiday+

1983 Roosevelt Sykes+

1996 Bryan James "Chas" Chandler+

2006 Sam Myers+

2007 Bill Perry+

2014 Ernie Lancaster+

Harriet Lewis*

Janice Scroggins*

Deano Matthias*

1925 Peppermint Harris*

1939 Spencer Davis*

1940 Margie Evans*

1942 Zoot Money*

1947 Abraham „Abe“ Laboriel*

1959 Billie Holiday+

1983 Roosevelt Sykes+

1996 Bryan James "Chas" Chandler+

2006 Sam Myers+

2007 Bill Perry+

2014 Ernie Lancaster+

Harriet Lewis*

Janice Scroggins*

Deano Matthias*

Happy Birthday

Abraham „Abe“ Laboriel *17.07.1947

Abraham „Abe“ Laboriel (* 17. Juli 1947 in Mexiko-Stadt) ist ein amerikanischer Bassist des Fusion-Jazz.

Laboriel ist Sohn eines Gitarrenlehrers und verlor mit vier Jahren die Kuppe seines linken Zeigefingers. Er lernte Gitarre bei seinem Vater und spielte als Rock'n Roll-Gitarrist in Mexiko, studierte jedoch zwei Jahre lang Ingenieurwissenschaften, bevor er sich für die Musik entschied und ab 1972 am Berklee College of Music Komposition studierte. Während des Studiums wechselte er zur Bassgitarre und spielte in Gruppen um Gary Burton und in der Bostoner Aufführung des Musicals „Hair“. 1973 war er für kurze Zeit Mitglied des Count Basie Orchestra, tourte mit Musikern wie Michel Legrand und Johnny Mathis. Auf Anraten von Henry Mancini zog er schließlich 1977 nach Los Angeles.

Dort arbeitete er sehr erfolgreich als Studiomusiker[1] und war an Film-Musiken beteiligt wie z.B. für Die Farbe Lila oder Nine to Five. Daneben spielte er mit Lee Ritenour, den er auf acht Alben begleitete, aber auch mit John Klemmer, George Benson, Larry Carlton, Don und Dave Grusin, Al Jarreau, Ella Fitzgerald, Herbie Hancock, David Benoit, Manhattan Transfer, Michael Jackson, Aretha Franklin, Tania Maria, Joe Sample, John Handy, Chris Beckers, Donald Fagen oder Diane Schuur.

Darüber hinaus gründete er 1980 die Band Koinonia, die immerhin vier durchaus erfolgreiche Alben herausbrachte. 1994 trat er bei verschiedenen europäischen Festivals auf. 2005 wurde ihm vom Berklee College of Music die Ehrendoktorwürde verliehen.[2]

Laboriel ist der Vater des US-amerikanischen Schlagzeugers Abe Laboriel Jr..

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abe_Laboriel

braham Laboriel, Sr. (born July 17, 1947) is a Mexican bassist who has played on over 4,000 recordings and soundtracks.[1] Guitar Player Magazine described him as "the most widely used session bassist of our time".[2][3] Laboriel is the father of drummer Abe Laboriel Jr. and of producer, songwriter, and film composer Mateo Laboriel.

Laboriel was born in Mexico City. Originally a classically trained guitarist, he switched to bass guitar while studying at the Berklee College of Music. Henry Mancini encouraged Laboriel to move to Los Angeles, California and pursue a recording career.[4] His brother was the late Mexican rock & roll singer Johnny Laboriel.[5] Their parents were Honduran immigrants from the Garifuna coast.[5]

Laboriel has worked with artists of many music genres including the following:

Al Jarreau, George Benson, Alan Silvestri, Alvaro Lopez and Res-Q Band, Alvin Slaughter, Don Felder, Andraé Crouch, Andy Pratt, Andy Summers, Barbra Streisand, Billy Cobham, Carlos Skinfill, Chris Isaak, Christopher Cross, Crystal Lewis, Dave Grusin, Djavan, Dolly Parton, Don Moen, Donald Fagen, Elton John, Engelbert Humperdinck, Freddie Hubbard, Hanson, Herb Alpert, Herbie Hancock, Johnny Hallyday, Keith Green, Kelly Willard, Lalo Schifrin, Larry Carlton, Lee Ritenour, Leo Sayer, Lisa Loeb, Madonna, Michael Jackson, Nathan Davis, Paul Jackson Jr., Paul Simon, Quincy Jones, Ray Charles, Ron Kenoly, Russ Taff, Stevie Wonder, and Umberto Tozzi.

When Laboriel recorded his three solo albums ‒ Dear Friends, Guidum, and Justo & Abraham, he recruited a cast of musicians that included Alex Acuña, Al Jarreau, Jim Keltner, Phillip Bailey, Ron Kenoly, and others. His son Abe Laboriel Jr. performed drums.

Laboriel was a founding member of the bands, Friendship and Koinonia. He plays live regularly with Greg Mathieson, drummer Bill Maxwell, and Justo Almario. Laboriel is now in the band Open Hands with Justo Almario, Greg Mathieson, and Bill Maxwell.

In 2005, Abraham was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Music by the Berklee College of Music.

Laboriel was born in Mexico City. Originally a classically trained guitarist, he switched to bass guitar while studying at the Berklee College of Music. Henry Mancini encouraged Laboriel to move to Los Angeles, California and pursue a recording career.[4] His brother was the late Mexican rock & roll singer Johnny Laboriel.[5] Their parents were Honduran immigrants from the Garifuna coast.[5]

Laboriel has worked with artists of many music genres including the following:

Al Jarreau, George Benson, Alan Silvestri, Alvaro Lopez and Res-Q Band, Alvin Slaughter, Don Felder, Andraé Crouch, Andy Pratt, Andy Summers, Barbra Streisand, Billy Cobham, Carlos Skinfill, Chris Isaak, Christopher Cross, Crystal Lewis, Dave Grusin, Djavan, Dolly Parton, Don Moen, Donald Fagen, Elton John, Engelbert Humperdinck, Freddie Hubbard, Hanson, Herb Alpert, Herbie Hancock, Johnny Hallyday, Keith Green, Kelly Willard, Lalo Schifrin, Larry Carlton, Lee Ritenour, Leo Sayer, Lisa Loeb, Madonna, Michael Jackson, Nathan Davis, Paul Jackson Jr., Paul Simon, Quincy Jones, Ray Charles, Ron Kenoly, Russ Taff, Stevie Wonder, and Umberto Tozzi.

When Laboriel recorded his three solo albums ‒ Dear Friends, Guidum, and Justo & Abraham, he recruited a cast of musicians that included Alex Acuña, Al Jarreau, Jim Keltner, Phillip Bailey, Ron Kenoly, and others. His son Abe Laboriel Jr. performed drums.

Laboriel was a founding member of the bands, Friendship and Koinonia. He plays live regularly with Greg Mathieson, drummer Bill Maxwell, and Justo Almario. Laboriel is now in the band Open Hands with Justo Almario, Greg Mathieson, and Bill Maxwell.

In 2005, Abraham was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Music by the Berklee College of Music.

Case of the Blues-Abraham Laboriel.mov

The extraordinary bass player Abraham Laboriel started off with a little

improv slow blues riff, then the rest of the band joined in making it

up as they played. Hadley Hockensmith on guitar, Bill Maxwell on drums,

Greg Mathieson on organ, and Phil Driscoll on trumpet. Phil also mashed

up some lyrics from 2 or 3 songs, made up a few others and the result

is this infectious blues number I'm calling "Case of the Blues." Great

musicians making fantastic music on the fly.

Coot Grant *17.07.1893, +unbekannt

(Leola B. Pettigrew)

Coot Grant war der Künstlername der Sängerin Leola B. Pettigrew, die nach ihrer Heirat mit Wesley „Kid“ Wilson, der auch musikalisch ihr Partner war, Leola Wilson hieß. Sie lernten sich 1905 kennen; zuvor war Coot Grant als Tänzerin in Vaudeville-Truppen aufgetreten. In der Zeit vor dem Kriegsausbruch vor 1914 war sie durch Europa und Südafrika getourt; dabei wurde sie von ihrem Mann am Klavier oder der Orgel begleitet. Sie traten auch unter Pseudonym wie Patsy Hunter oder bizarren Bühnennamen wie Catjuice Charlie, Kid Wilson, Jenkins, Socks und Sox Wilson auf.

Grant und Wilson traten und nahmen auch unter den Bezeichnungen Kid and Coot bzw. Hunter and Jenkins mit Jazzmusikern wie Fletcher Henderson, Mezz Mezzrow, Sidney Bechet und Louis Armstrong auf, gastierten in Musikkomödien, reisenden Shows und Revuen. 1933 hatte sie einen Auftritt in dem Film Emperor Jones an der Seite des Sängers Paul Robeson.

In Erinnerung bleibt Grant auch durch ihre Aktivitäten als Songwriterin; das Paar schrieb zusammen ungefähr 400 Songs, am bekanntesten „Gimme A Pigfoot“, der einer der Hits der Bluessängerin Bessie Smith war. Weitere bekannte Titel waren „Dem Socks Dat My Pappy Wore“ und der „Throat Cutting Blues“. Grant nahm auch unter eigenem Namen 1926 einige Country Blues-Titel in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Gitarristen Blind Blake auf.

Mitte der 1930er Jahre ließ der Erfolg des Paars nach; es entstanden noch Aufnahmen im Jahr 1938. Mezz Mezzrow holte dann die beiden Ende 1947 ins Studio, als er mit ihnen Material („Breathless Blues“, „Really the Blues“) für sein eigenes Label King Jazz einspielte. Grant trat noch weiter auf, nachdem sich ihr Mann 1948 aus der Musikszene zurückzog, geriet aber dann in Vergessenheit, sodass über ihren weiteren Verbleib nichts bekannt ist.

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coot_Grant

Coot Grant (June 17, 1893 – unknown)[1] was an American classic female blues, country blues, and vaudeville, singer and songwriter.[3] Her own stage craft, plus the double act with her husband and musical partner, Wesley "Kid" Wilson, was popular with African American audiences in the 1910s, 1920s and early 1930s.[2][4]

Biography

One of fifteen offspring, she was born Leola B. Pettigrew in Birmingham, Alabama, United States.[2] The first part of her eventual stage name came from a derivation of her childhood nickname, 'Cutie'. She began work in 1900 in Atlanta, Georgia, appearing in vaudeville, and the following year toured South Africa and across Europe with Mayme Remington's Pickaninnies. She was sometimes billed as Patsy Hunter. In 1913, she married the singer, Isiah I. Grant, and they worked on stage together before his death in 1920. She married Wesley Wilson the same year,[2] but he surpassed her on stage names being later variously billed as Catjuice Charlie (in a brief duo with Pigmeat Pete), Kid Wilson, Jenkins, Socks, and Sox Wilson. He played both piano and organ, whilst Coot Grant strummed guitar as well as sing and dance.[3]

The duo's billing also varied between Grant and Wilson, Kid and Coot, and Hunter and Jenkins, as they went on to appear and later record with Fletcher Henderson, Mezz Mezzrow, Sidney Bechet, and Louis Armstrong. Their variety was such that they performed separately and together in vaudeville, musical comedies, revues and traveling shows. This ability to adapt also saw them appear in the 1933 film, The Emperor Jones, alongside Paul Robeson.[3]

In addition to this, the twosome wrote in excess of 400 songs over their working lifetime.[5] That list included "Gimme a Pigfoot (And a Bottle of Beer)" (1933) and "Take Me for a Buggy Ride", which were both made famous by Bessie Smith's recording of the songs, plus "Find Me at the Greasy Spoon" and "Prince of Wails" for Fletcher Henderson. Their own renditions included the diverse, "Come on Coot, Do That Thing" (1925), "Dem Socks Dat My Pappy Wore," and "Throat Cutting Blues" (although the latter remains unreleased)."[3]

In 1926, Grant joined up with Blind Blake, and recorded a selection of country blues renditions.[3] These were Blake's debut recordings.[2] Although Grant and Wilson's act, once seen as a serious rival to Butterbeans and Susie,[2] began to lose favor with the public by the middle of the 1930s, they recorded further songs in 1938.[3] Their only child, Bobby Wilson, was born in 1941.[6] By 1946, and after Mezz Mezzrow had founded his King Jazz record label, he engaged them as songwriters.[3] In that year, the association led to their final recording session backed by a quintet incorporating Bechet and Mezzrow.[6] In December 1948, The Record Changer magazine reported that Coot Grant and Kid Sox Wilson opened a new show in Newark, NJ, "an old time revue called 'Holiday in Blues.'"

Wilson retired in ill health shortly thereafter,[5] but Grant continued performing into the 1950s.[3] In a May 1951 Record Changer magazine poll, she was listed among a roster of notable female vocalists, although she received less than five votes in the poll, while the top spot - Bessie Smith - received 381 votes. In January 1953, one commentator noted that the couple had moved from New York to Los Angeles, but were in considerable financial hardship.[7] Grant's popularity waned to such an extent that no official details have been uncovered concerning her death.[3]

Her entire recorded work, both with and without Wilson, was made available in three chronological volumes in 1998 by Document Records.

Biography

One of fifteen offspring, she was born Leola B. Pettigrew in Birmingham, Alabama, United States.[2] The first part of her eventual stage name came from a derivation of her childhood nickname, 'Cutie'. She began work in 1900 in Atlanta, Georgia, appearing in vaudeville, and the following year toured South Africa and across Europe with Mayme Remington's Pickaninnies. She was sometimes billed as Patsy Hunter. In 1913, she married the singer, Isiah I. Grant, and they worked on stage together before his death in 1920. She married Wesley Wilson the same year,[2] but he surpassed her on stage names being later variously billed as Catjuice Charlie (in a brief duo with Pigmeat Pete), Kid Wilson, Jenkins, Socks, and Sox Wilson. He played both piano and organ, whilst Coot Grant strummed guitar as well as sing and dance.[3]

The duo's billing also varied between Grant and Wilson, Kid and Coot, and Hunter and Jenkins, as they went on to appear and later record with Fletcher Henderson, Mezz Mezzrow, Sidney Bechet, and Louis Armstrong. Their variety was such that they performed separately and together in vaudeville, musical comedies, revues and traveling shows. This ability to adapt also saw them appear in the 1933 film, The Emperor Jones, alongside Paul Robeson.[3]

In addition to this, the twosome wrote in excess of 400 songs over their working lifetime.[5] That list included "Gimme a Pigfoot (And a Bottle of Beer)" (1933) and "Take Me for a Buggy Ride", which were both made famous by Bessie Smith's recording of the songs, plus "Find Me at the Greasy Spoon" and "Prince of Wails" for Fletcher Henderson. Their own renditions included the diverse, "Come on Coot, Do That Thing" (1925), "Dem Socks Dat My Pappy Wore," and "Throat Cutting Blues" (although the latter remains unreleased)."[3]

In 1926, Grant joined up with Blind Blake, and recorded a selection of country blues renditions.[3] These were Blake's debut recordings.[2] Although Grant and Wilson's act, once seen as a serious rival to Butterbeans and Susie,[2] began to lose favor with the public by the middle of the 1930s, they recorded further songs in 1938.[3] Their only child, Bobby Wilson, was born in 1941.[6] By 1946, and after Mezz Mezzrow had founded his King Jazz record label, he engaged them as songwriters.[3] In that year, the association led to their final recording session backed by a quintet incorporating Bechet and Mezzrow.[6] In December 1948, The Record Changer magazine reported that Coot Grant and Kid Sox Wilson opened a new show in Newark, NJ, "an old time revue called 'Holiday in Blues.'"

Wilson retired in ill health shortly thereafter,[5] but Grant continued performing into the 1950s.[3] In a May 1951 Record Changer magazine poll, she was listed among a roster of notable female vocalists, although she received less than five votes in the poll, while the top spot - Bessie Smith - received 381 votes. In January 1953, one commentator noted that the couple had moved from New York to Los Angeles, but were in considerable financial hardship.[7] Grant's popularity waned to such an extent that no official details have been uncovered concerning her death.[3]

Her entire recorded work, both with and without Wilson, was made available in three chronological volumes in 1998 by Document Records.

Harriet Lewis *17.07.

Eine Nacht mit Jazz, Blues, moderner Musik, mit einem Hauch geschmackvollen Gospels.

Harriet Lewis; eine international, professionelle Künstlerin/Songschreiberin,

die bereits 8 CDs' vorweisen kann.

Sie ist eine beeindruckende, ansprechende und absolut kontrollierte Sängerin, gebürtig von der Ostküste der USA.

Harriet geht bis zu Ihrer Grenze, um uns zu zeigen und zu beweisen, dass sie eine wirkliche 'First Lady' dieses Millenniums ist. Sie weiß, was sie will und wie sie dies umsetzten kann.

Sie stellt in Ihrer Art eine engagierte, selbstlose, verlässliche und feminine "Grande Dame" der Musik dar.

Harriet ist eine Zusammenstellung aus rauhem/klammen Blues, sexy/romantischen Balladen und gesungenem traditionellen Gospel.

Harriet Lewis, beweißt sich als Legende ihrer Aera.

1) Harriet Lewis wurde in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, als Tochter jamaikanischer Einwanderer geboren.

a) Mit 12 Jahren hat sie in der heimischen "Baptisten Kirche" zu singen angefangen. Dann wurde sie selbst Leiterin des Baptisten Chors, der in Pennsylvania und über dessen Grenzen hinaus, Konzerte bestritt.

b) Später bildete Sie mit Hilfe Ihrer Mutter einen Kinderchor, bestehend aus 5-17 jährigen Kindern.

2) Ihre erste musikalische Grundausbildung erhielt Harriet am Sherwood Recreation Center in Philadelphia, PA.

a) Dort studierte sie Tanz, was die verschiedenen Stilrichtungen, wie Ballet, Tab, Modern Jazz, African und Modeling beinhaltete.

b) Während dieser Zeit hat sie begonnen, diese verschiedenen Tanzstile in Ihre Gesangsvorführungen einzubauen; was ihr wiederum half, viele Amateur- Wettbewerbe zu gewinnen.

3) 1967, wurde Harriet, unter dem Label "Philadelphia International Records", eine der Gründungsmitglieder der "FORGET ME KNOTS".

a) Diese Verbindung und ihr stimmliches Talent, wurden von Musik produzierenden Größen, wie:

PATTIE LABELLE, BILLY PAUL, THE O JAY'S, 3 DEGREES, INTRUDERS,DEL PHONICS,HAROLD MELVIN & THE BLUE NOTES, DONALD BYRD & BLACK BIRDS, TEDDY PENDEGRAST, BOBBY HUMPHREY, FOUR TOPS, PIECES OF A DREAM & MELBA MORE

verehrt und gefragt.

b)Später sang sie für die Plattenfirmen "Blue Note Label", "Golden Production" und "Sal Sol Orchestra" als Background-Sängerin.

4) Nachdem Harriet ihre theoretische Stimm- und Musikausbildung bei der Philadelphia Musik Akademie abgeschlossen hatte, unterschrieb sie einen 2 Jahresvertrag für eine Konzerttournee mit Philly Groove Recording Künstler "Raw Image".

5) 1973, gründete Harriet ihre erste eigene Band "POSH" und wurde als absolute #1, der weiblichen Jazzsängerinnen in Philadelphia, PA. anerkannt und verehrt.

6) 1980, ist Harriet in die amerikanische Armee eingetreten, wo sie während ihres Einsatzes weiterhin Konzerte gab. Als sie an der West Point Military Academy stationiert war, gab sie Unterricht in Theater- und Gesangskunst. In dieser Zeit hat Harriet ein musikalisches Wettbewerbprogramm ins Leben gerufen, wodurch Sie sehr beliebt wurde.

7) Harriet wurde auch engagiert, um vor Würdenträger aus Japan, Afrika, Korea, Frankreich und den U.S.A. zu singen. Während dieser Zeit, teilte sie sich die Bühne mit Berühmtheiten, wie das Charlie Byrd Trio, Gregory Hines, George Benson, Earl Klugh, Jennifer Holiday und vielen vielen anderen.

8) Nachdem Harriet nach Stuttgart, Deutschland, umgezogen war, hat sie begonnen, in hiesigen Hotels' und Clubs' aufzutreten. Dies führte dazu, dass sie die besten deutschen Musiker kennenlernte, darunter auch Pops Wilson, mit dessen Orchestra sie zusammen bis heute noch auftritt. Zwischen Harriet und Pops entstand eine außergewöhnlich, "magische" Freundschaft, die durch ihre erste gemeinsame CD " A touch of elegance" besiegelt wurde.

9) Harriet hat in der Zwischenzeit zwölf weitere CDs' produziert. Ausschnitte können sie sich unter der Rubrik "Discography" anschauen und anhören.

Harriet eröffnete Konzerte für LUTHER VANDROSS, MARIAH CAREY, THE WEATHER GIRLS,ERIC CLAPTON,LISA STANSFIELD,CRASH TEST DUMMIES,HEINO,"Comedian" OTTO,MICHAEL BOLTON,"'THE KING OF POP" MICHAEL JACKSON,RAY CHARLES und vielen anderen. Siehe Ihre "Musikbiographie".

10) Durch Ihren musikalischen Erfolg wurde Harriet, 1995, als beste europäische Soul, Blues, Jazz Sängerin vom deutschen Rock- + Popmusikverband ev. mit dem Musik Oskar ausgezeichnet.

Harriet ist eine Künstlerin, deren Energie und musikalische Leidenschaft, durch stetige qualitative Korrektur und kritische Verbesserung Ihrer Auftritte, das Licht ihres Sternes zum gluehen bringt.

Treue Fans sagten einmal, dass Harriet ihrem Publikum als Prinzessin gegenübertritt und als KOENIGIN die Bühne wieder verlässt.

Wie ein geschliffener Diamant, ist Harriet Lewis ein musikalisches Genie, was einen königlichen Rahmen verdient.

http://www.swingin-wiwa.de/2007/themen/interpreten/soulfinger/harriet-lewis.htm

Harriet Lewis was born in 1951 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania of God fearing Jamaican parents. She began singing in her local Baptist Church when she was 12 and became the director of their Baptist choir who travelled throughout Philadelphia. She later formed a junior choir of her own with the help of her mother consisting of children between the ages of 5 and 17. They performed concerts throughout the Eastern coastal region of the US singing a cappella vocal arrangements by Harriet.

She received her first formal training at Sherwood Recreation Centre in Philly and here she studied dance including ballet, tap, modern jazz, African and modelling and it was here that she began to incorporate dance styles into her vocal performances winning many local talent competitions. In 1967 Harriet became one of the founder members of the Philadelphia International Records recording group ‘The Forget Me Knots’ and it was with this label that she recorded background vocals with Pattie Labelle, Billy Paul, The O Jay’s, Prince Charles’ main squeeze The Three Degrees, The Intruders, The Del Phonics, The Four Tops, the wonderful Harold Melvin and The Blue Notes, the terrific Donald Byrd, etc etc; It was with the latter group that she eventually moved to the famous Blue Note label to work on background tracks for Blue Note, Gold Production and Sal Soul Orchestra.

After completing Voice and Music Theory at the Philadelphia Music Academy Harriet signed on for a two-year road tour with Philly groove artists ‘Raw Image’. In 1973 Harriet formed her own band ‘POSH’, which soon became recognised as one of the foremost bands in Philadelphia. When she arrived in Stuttgart, Germany she worked the nightclub and hotel circuits and was soon in demand by some of Germany’s elite jazz and blues musicians. She has opened for Luther Vandross, Eric Clapton, Mariah Carey, Michael Jackson, Ray Charles and many others. From a cappella, gospel to full-blown jazz orchestra’s Harriet has done it all.

http://www.shakedownblues.co.uk/biography_read.php?e_id=86She received her first formal training at Sherwood Recreation Centre in Philly and here she studied dance including ballet, tap, modern jazz, African and modelling and it was here that she began to incorporate dance styles into her vocal performances winning many local talent competitions. In 1967 Harriet became one of the founder members of the Philadelphia International Records recording group ‘The Forget Me Knots’ and it was with this label that she recorded background vocals with Pattie Labelle, Billy Paul, The O Jay’s, Prince Charles’ main squeeze The Three Degrees, The Intruders, The Del Phonics, The Four Tops, the wonderful Harold Melvin and The Blue Notes, the terrific Donald Byrd, etc etc; It was with the latter group that she eventually moved to the famous Blue Note label to work on background tracks for Blue Note, Gold Production and Sal Soul Orchestra.

After completing Voice and Music Theory at the Philadelphia Music Academy Harriet signed on for a two-year road tour with Philly groove artists ‘Raw Image’. In 1973 Harriet formed her own band ‘POSH’, which soon became recognised as one of the foremost bands in Philadelphia. When she arrived in Stuttgart, Germany she worked the nightclub and hotel circuits and was soon in demand by some of Germany’s elite jazz and blues musicians. She has opened for Luther Vandross, Eric Clapton, Mariah Carey, Michael Jackson, Ray Charles and many others. From a cappella, gospel to full-blown jazz orchestra’s Harriet has done it all.

Janice Scroggins *17.07.1955

Janice Scroggins (* 1955 in Idabel, Oklahoma; † 27. Mai 2014 in Portland, Oregon[1][2]) war eine US-amerikanische Blues- und Jazzpianistin, die in der Musikszene von Oregon aktiv war.

Janice Scroggins erhielt ab drei Jahren Klavierunterricht von ihrer Mutter und ihrer Großmutter, die beide Kirchenorganistinnen waren; letztere prägte ihren am Stride-Piano orientierten Stil. Sie besuchte die afroamerikanische Booker T. Washington School. Musikalisch geprägt wurde sie von Gospelmusikern wie Sister Rosetta Tharpe und Brother Joe May. Später lebte sie in Oakland, bevor sie 1978 mit ihrer Tochter Arietta nach Portland zog. Dort arbeitete sie u. a. mit den Sängerinnen Linda Hornbuckle und Thara Memory. 1987 entstand das Album Janice Scroggins Plays Scott Joplin (Flying Heart), das für den Grammy Award nominiert wurde[1]. Im Bereich des Jazz war sie zwischen 1987 und 2008 an acht Aufnahmesessions beteiligt, u. a. mit Eddie Harris und Akbar DePriest[3]. 2013 wurde sie in die Oregon Music Hall of Fame aufgenommen; Anfang 2014 erschien ihr zweites und letztes Album Piano Love. Ihren letzten größeren Auftritt hatte sie Anfang 2014 auf dem Portland Jazz Festival[4]. Sie starb im Mai 2014 an den Folgen eines Herzinfarktes während des Unterrichts am Portland Community College.

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Janice_Scroggins

Mary Reynolds-Lead vocal

Janice Scroggins-keyboards

- Tenor Sax (solo)

Dave Mills (Mills Davis)-Trumpet

Warren Rand-Alto sax

Jonathan Drechsler- bass

Guy Maxwell (?)-drums

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bfKSViAQ3AA#t=48

Janet Scroggins (July 17, 1955 – May 27, 2014) was a jazz pianist in Portland, Oregon.

Early life

Scroggins was born in 1955 in Idabel, Oklahoma, to Henry and Mary Scroggins. Her mother and grandmother were church pianists and organists. She moved to the Albina community of Portland in 1978.[1]

Musical career

Scroggins performed with Portland area musicians including Linda Hornbuckle, Thara Memory, Curtis Salgado, and Mel Brown. She also played with the Norman Sylvester Blues Band and was a session musician for several other artists.[2]

Tributes

In 1992, Scroggins was inducted into the Cascade Blues Association Hall of Fame. She was inducted into the Oregon Music Hall of Fame in 2013.

Early life

Scroggins was born in 1955 in Idabel, Oklahoma, to Henry and Mary Scroggins. Her mother and grandmother were church pianists and organists. She moved to the Albina community of Portland in 1978.[1]

Musical career

Scroggins performed with Portland area musicians including Linda Hornbuckle, Thara Memory, Curtis Salgado, and Mel Brown. She also played with the Norman Sylvester Blues Band and was a session musician for several other artists.[2]

Tributes

In 1992, Scroggins was inducted into the Cascade Blues Association Hall of Fame. She was inducted into the Oregon Music Hall of Fame in 2013.

The Esquires - Unemployment Blues

Jan Celt- Guitar, vocal, bandleaderMary Reynolds-Lead vocal

Janice Scroggins-keyboards

- Tenor Sax (solo)

Dave Mills (Mills Davis)-Trumpet

Warren Rand-Alto sax

Jonathan Drechsler- bass

Guy Maxwell (?)-drums

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bfKSViAQ3AA#t=48

Margie Evans *17.07.1940

Margie Evans (born July 17, 1940) is an American blues singer and songwriter.[2] She recorded mainly in the 1970s and 1980s, and secured two hit singles on the US Billboard R&B chart. She has variously worked with Johnny Otis and Bobby Bland.

Her main influences were Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, Big Maybelle and Big Mama Thornton.[3]

In addition to her musicianship, Evans is noted as a motivational speaker and rights activist, as well as a promoter of the legacy of blues music.

Marjorie Ann Johnson was born in Shreveport, Louisiana, United States.[1] Raised as a devout church goer, Evans early exposure to music was via gospel.[5] In 1958, she moved to Los Angeles. She initially sang as a backing vocalist with Billy Ward between 1958 and 1964, before joining the Ron Marshall Orchestra between 1964 and 1969. She then successfully auditioned to join Johnny Otis Band.[1] During her four year stay there, she performed on The Johnny Otis Show Live at Monterey and Cuttin' Up albums. In addition to her recording and performing duties, Evans used her influence to help set up the Southern California Blues Society to help promote the art form through education and sponsorship.[5]

Evans commenced her solo career in 1973, and found almost immediate chart success. Her track "Good Feeling" (United Artists 246) entered the R&B chart on June 30, 1973 for four weeks, reaching number 55. However, it was another four years before "Good Thing Queen - Part 1" (ICA 002) entered the same chart listing on July 9, 1977 for eight weeks, peaking at number 47.[1] In 1975 she supplied backing vocals on Donald Byrd's album, Stepping into Tomorrow.[6]

Also sandwiched between these hits, in November 1975, Evans appeared on German television filmed at the Berlin based Jazz Tage concert with Johnny "Guitar" Watson, Bo Diddley and James Booker.[7] Using Bobby Bland as her record producer and part-time song writing partner, Evans co-wrote the song "Soon As the Weather Breaks", which reached number 76 (R&B) for Bland in 1980.[1][8]

In 1980, Evans performed at the San Francisco Blues Festival and Long Beach Blues Festival, repeating the feat at the latter a year later. Her touring saw Evans take part in the American Folk Blues Festivals in 1981, 1982 and 1985.[9] In 1983, Evans was granted the Keepin' the Blues Alive Award by the Blues Foundation.[3]

Still performing into the early 1990s, Evans toured the States, Canada and Europe as well as appearing with Jay McShann at the Toronto Jazz Festival.[3] In the same decade, Evans continued her welfare work, by helping to organise the 5-4 Optimist Club for children from the South Central Los Angeles district.[5] Her 1996 album, Drowning in the Sea of Love is her most recent recorded output.

Her main influences were Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, Big Maybelle and Big Mama Thornton.[3]

In addition to her musicianship, Evans is noted as a motivational speaker and rights activist, as well as a promoter of the legacy of blues music.

Marjorie Ann Johnson was born in Shreveport, Louisiana, United States.[1] Raised as a devout church goer, Evans early exposure to music was via gospel.[5] In 1958, she moved to Los Angeles. She initially sang as a backing vocalist with Billy Ward between 1958 and 1964, before joining the Ron Marshall Orchestra between 1964 and 1969. She then successfully auditioned to join Johnny Otis Band.[1] During her four year stay there, she performed on The Johnny Otis Show Live at Monterey and Cuttin' Up albums. In addition to her recording and performing duties, Evans used her influence to help set up the Southern California Blues Society to help promote the art form through education and sponsorship.[5]

Evans commenced her solo career in 1973, and found almost immediate chart success. Her track "Good Feeling" (United Artists 246) entered the R&B chart on June 30, 1973 for four weeks, reaching number 55. However, it was another four years before "Good Thing Queen - Part 1" (ICA 002) entered the same chart listing on July 9, 1977 for eight weeks, peaking at number 47.[1] In 1975 she supplied backing vocals on Donald Byrd's album, Stepping into Tomorrow.[6]

Also sandwiched between these hits, in November 1975, Evans appeared on German television filmed at the Berlin based Jazz Tage concert with Johnny "Guitar" Watson, Bo Diddley and James Booker.[7] Using Bobby Bland as her record producer and part-time song writing partner, Evans co-wrote the song "Soon As the Weather Breaks", which reached number 76 (R&B) for Bland in 1980.[1][8]

In 1980, Evans performed at the San Francisco Blues Festival and Long Beach Blues Festival, repeating the feat at the latter a year later. Her touring saw Evans take part in the American Folk Blues Festivals in 1981, 1982 and 1985.[9] In 1983, Evans was granted the Keepin' the Blues Alive Award by the Blues Foundation.[3]

Still performing into the early 1990s, Evans toured the States, Canada and Europe as well as appearing with Jay McShann at the Toronto Jazz Festival.[3] In the same decade, Evans continued her welfare work, by helping to organise the 5-4 Optimist Club for children from the South Central Los Angeles district.[5] Her 1996 album, Drowning in the Sea of Love is her most recent recorded output.

Margie Evans - Margie's Boogie

Zoot Money *17.07.1942

http://www.bluespower-bs.de/news.html

Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band war eine britische Soul-Band, die Mitte der 1960er Jahre vornehmlich in Großbritannien erfolgreich war.

Zoot selbst spielte Orgel und sang in einem funkigen, vom Blues herkommenden Stil. Er beherrschte mit seiner kraftvollen, unverwechselbaren Persönlichkeit jeden Song und wurde von einer hervorragenden Band begleitet. Zu dieser gehörte unter anderem Andy Summers, der später mit The Police noch viel berühmter werden sollte.

In die Charts hat es die Band einmal geschafft, mit der Single Big Time Operator, in der Zoot sich in aller Bescheidenheit selbst beschreibt.

Zoot gründete später eine experimentelle Gruppe namens Dantalion’s Chariot, bevor er Organist bei Eric Burdons Animals wurde.

Zoot selbst spielte Orgel und sang in einem funkigen, vom Blues herkommenden Stil. Er beherrschte mit seiner kraftvollen, unverwechselbaren Persönlichkeit jeden Song und wurde von einer hervorragenden Band begleitet. Zu dieser gehörte unter anderem Andy Summers, der später mit The Police noch viel berühmter werden sollte.

In die Charts hat es die Band einmal geschafft, mit der Single Big Time Operator, in der Zoot sich in aller Bescheidenheit selbst beschreibt.

Zoot gründete später eine experimentelle Gruppe namens Dantalion’s Chariot, bevor er Organist bei Eric Burdons Animals wurde.

George Bruno Money, known as Zoot Money (born 17 July 1942, Bournemouth (at that time in Hampshire), England) is a British vocalist, keyboardist and bandleader best known for his playing of the Hammond organ and association with his Big Roll Band. Inspired by Jerry Lee Lewis and Ray Charles, he was drawn to rock and roll music and became a leading light in the vibrant music scene of Bournemouth and Soho during the 1960s. Money has been associated with Eric Burdon, Steve Marriott, Kevin Coyne, Rocket 88, Snowy White, Mick Taylor, Spencer Davis, Geno Washington, Brian Joseph Friel, the Hard Travelers, Widowmaker and Alan Price. He is also known as a bit part and character actor.

He was born George Bruno Money in Bournemouth, Hampshire, in 1942, of a family that were Italian immigrants, though of English descent on his father's side. He played the French horn and sang in the school choir as a boy. During the mid-1950s, he discovered Jerry Lee Lewis and Ray Charles, took up keyboard and, by the beginning of the 1960s, Hammond organ. He took his name from Zoot Sims after seeing him in concert.[1]

In early autumn 1961 Zoot Money formed the Big Roll Band, with himself as vocalist, Roger Collis on lead guitar, pianist Al Kirtley (later of Trendsetters Limited), bassist Mike "Monty" Montgomery and drummer Johnny Hammond. In 1962 drummer Pete Brookes replaced Hammond at the same time as bassist Johnny King and tenor sax player Kevin Drake joined the band.[2]

The Big Roll Band played soul, jazz and R&B, moving with musical trends as the now established R&B movement moved into the Swinging Sixties and became associated with the burgeoning "Soho scene". Money's antics as a flamboyant frontman were a feature of the band's act. During 1964 the Big Roll Band started playing regularly at the Flamingo Club in Soho, London until Money joined Alexis Korner's Blues Incorporated. During the mid-1960s the lead guitarist in the Big Roll Band was Andy Summers, who later found international fame as one of the three members of the Police. In July 1967 the Big Roll Band became Dantalian's Chariot and in spite of a lack of chart success the band found itself at the heart of a new counter culture, sharing concert line-ups with Pink Floyd, Soft Machine and the Crazy World of Arthur Brown. A single, "Madman Running Through the Fields", was released in 1967 but in April 1968 Dantalian's Chariot was disbanded.[3] During 1968, with a brief stint in the United States with Eric Burdon & the New Animals, Money moved to the States. During this period he began attracting acting roles and started a parallel career with character appearances in film and TV dramas.

In June 1970, Money contributed piano to the improvisational studio jam session led by former Fleetwood Mac guitarist Peter Green; and edited into six tracks that formed Green's experimental release, The End of the Game. Also in the 1970s, Money appeared with different acts including the poetry and rock band Grimms, Ellis, Centipede, Kevin Ayers and Kevin Coyne. Money toured with Coyne and appeared on Coyne's double album In Living Black And White (1976), which was recorded at live performances, and on his two studio albums Heartburn (1976) and Dynamite Daze (1978). Money signed to Paul McCartney's record label MPL Communications in 1980 and recorded Mr. Money produced by Jim Diamond. In 1981 Steve Marriott and Ronnie Lane[4] formed a band with Money, bass player Jim Leverton, drummer Dave Hynes and saxophone player Mel Collins to record the album The Majic Mijits. The album features songs by Lane and Marriott but due to Lane's multiple sclerosis, they were unable to tour to promote it. It was eventually released nineteen years later.[5]

In 1994 Money appeared with Alan Price and the Electric Blues Company alongside vocalist and guitarist Bobby Tench, bassist Peter Grant and drummer Martin Wild, on A Gigster's Life for Me.[6] He continued to appear with Price at live appearances in the UK.[7] The Dantalian's Chariot album Chariot Rising was released in 1997, thirty years after it was recorded. In 1998 Money produced Ruby Turner's album Call Me by My Name,[8] and the Woodstock Taylor and the Aliens album Road Movie (2002), also contributing keyboards to both.[9] In 2002 he recorded tracks with Humble Pie for their album Back on Track released by Sanctuary Records.[10]

Money joined Pete Goodall to re-record the Thunderclap Newman UK hit single Something in the Air (2004) written by John "Speedy" Keene, which featured the last recorded performance by saxophonist Dick Heckstall-Smith.[11] In 2005 Money joined Goodall to record a CD of new songs by Goodall and Pete Brown. They went on to tour the UK under the name of Good Money.[12] In early 2006 Money and drummer Colin Allen joined vocalist Maggie Bell, bassist Colin Hodgkinson and guitarist Miller Anderson, in the British Blues Quintet.

He appeared with the RD Crusaders for the Teenage Cancer Trust at the "London International Music Show", on 15 June 2008.[13] In 2009 he appeared with Maggie Bell, Bobby Tench, Chris Farlowe and Alan Price, in the Maximum Rhythm and Blues Tour of thirty two British theatres.[14]

Acting career

As an actor Money appeared as a promotions man in the 1980 UK film Breaking Glass, and as a music-publishing executive in the 1981 Madness film Take It or Leave It. He also played one of Leonard Rossiter's fellow commuters dicing for first place across the River Thames, in the UK short film The Waterloo Bridge Handicap. Sometimes credited as G.B. Money or G.B, Money has appeared in a number of other small roles in British television programmes such as Bergerac, The Professionals, The Bill and Coronation Street. In 1979, Money also had a small role as the dim-witted Lotterby in the film version of Porridge. In 1992 and 1993 he appeared in the BBC sitcom Get Back as a dim but well meaning family friend 'Bungalow Bill' alongside Ray Winstone, Larry Lamb and Kate Winslet. In 2000 he starred in a film based on guitarist Syd Barrett, as a fanatical fan stalking the rock star Roger Bannerman in the underground cult film Remember a Day.

He was born George Bruno Money in Bournemouth, Hampshire, in 1942, of a family that were Italian immigrants, though of English descent on his father's side. He played the French horn and sang in the school choir as a boy. During the mid-1950s, he discovered Jerry Lee Lewis and Ray Charles, took up keyboard and, by the beginning of the 1960s, Hammond organ. He took his name from Zoot Sims after seeing him in concert.[1]

In early autumn 1961 Zoot Money formed the Big Roll Band, with himself as vocalist, Roger Collis on lead guitar, pianist Al Kirtley (later of Trendsetters Limited), bassist Mike "Monty" Montgomery and drummer Johnny Hammond. In 1962 drummer Pete Brookes replaced Hammond at the same time as bassist Johnny King and tenor sax player Kevin Drake joined the band.[2]

The Big Roll Band played soul, jazz and R&B, moving with musical trends as the now established R&B movement moved into the Swinging Sixties and became associated with the burgeoning "Soho scene". Money's antics as a flamboyant frontman were a feature of the band's act. During 1964 the Big Roll Band started playing regularly at the Flamingo Club in Soho, London until Money joined Alexis Korner's Blues Incorporated. During the mid-1960s the lead guitarist in the Big Roll Band was Andy Summers, who later found international fame as one of the three members of the Police. In July 1967 the Big Roll Band became Dantalian's Chariot and in spite of a lack of chart success the band found itself at the heart of a new counter culture, sharing concert line-ups with Pink Floyd, Soft Machine and the Crazy World of Arthur Brown. A single, "Madman Running Through the Fields", was released in 1967 but in April 1968 Dantalian's Chariot was disbanded.[3] During 1968, with a brief stint in the United States with Eric Burdon & the New Animals, Money moved to the States. During this period he began attracting acting roles and started a parallel career with character appearances in film and TV dramas.

In June 1970, Money contributed piano to the improvisational studio jam session led by former Fleetwood Mac guitarist Peter Green; and edited into six tracks that formed Green's experimental release, The End of the Game. Also in the 1970s, Money appeared with different acts including the poetry and rock band Grimms, Ellis, Centipede, Kevin Ayers and Kevin Coyne. Money toured with Coyne and appeared on Coyne's double album In Living Black And White (1976), which was recorded at live performances, and on his two studio albums Heartburn (1976) and Dynamite Daze (1978). Money signed to Paul McCartney's record label MPL Communications in 1980 and recorded Mr. Money produced by Jim Diamond. In 1981 Steve Marriott and Ronnie Lane[4] formed a band with Money, bass player Jim Leverton, drummer Dave Hynes and saxophone player Mel Collins to record the album The Majic Mijits. The album features songs by Lane and Marriott but due to Lane's multiple sclerosis, they were unable to tour to promote it. It was eventually released nineteen years later.[5]

In 1994 Money appeared with Alan Price and the Electric Blues Company alongside vocalist and guitarist Bobby Tench, bassist Peter Grant and drummer Martin Wild, on A Gigster's Life for Me.[6] He continued to appear with Price at live appearances in the UK.[7] The Dantalian's Chariot album Chariot Rising was released in 1997, thirty years after it was recorded. In 1998 Money produced Ruby Turner's album Call Me by My Name,[8] and the Woodstock Taylor and the Aliens album Road Movie (2002), also contributing keyboards to both.[9] In 2002 he recorded tracks with Humble Pie for their album Back on Track released by Sanctuary Records.[10]

Money joined Pete Goodall to re-record the Thunderclap Newman UK hit single Something in the Air (2004) written by John "Speedy" Keene, which featured the last recorded performance by saxophonist Dick Heckstall-Smith.[11] In 2005 Money joined Goodall to record a CD of new songs by Goodall and Pete Brown. They went on to tour the UK under the name of Good Money.[12] In early 2006 Money and drummer Colin Allen joined vocalist Maggie Bell, bassist Colin Hodgkinson and guitarist Miller Anderson, in the British Blues Quintet.

He appeared with the RD Crusaders for the Teenage Cancer Trust at the "London International Music Show", on 15 June 2008.[13] In 2009 he appeared with Maggie Bell, Bobby Tench, Chris Farlowe and Alan Price, in the Maximum Rhythm and Blues Tour of thirty two British theatres.[14]

Acting career

As an actor Money appeared as a promotions man in the 1980 UK film Breaking Glass, and as a music-publishing executive in the 1981 Madness film Take It or Leave It. He also played one of Leonard Rossiter's fellow commuters dicing for first place across the River Thames, in the UK short film The Waterloo Bridge Handicap. Sometimes credited as G.B. Money or G.B, Money has appeared in a number of other small roles in British television programmes such as Bergerac, The Professionals, The Bill and Coronation Street. In 1979, Money also had a small role as the dim-witted Lotterby in the film version of Porridge. In 1992 and 1993 he appeared in the BBC sitcom Get Back as a dim but well meaning family friend 'Bungalow Bill' alongside Ray Winstone, Larry Lamb and Kate Winslet. In 2000 he starred in a film based on guitarist Syd Barrett, as a fanatical fan stalking the rock star Roger Bannerman in the underground cult film Remember a Day.

British Blues Allstars - Blues Garage - 16.10.14

R.I.P.

Bill Perry +17.07.2007

Bill Perry (December 25, 1957 - July 17, 2007)[1] was an American blues musician. The guitarist, songwriter and singer toured throughout the U.S. and Europe. In the 1980s, he was the main guitarist for Richie Havens; he also toured with Garth Hudson and Levon Helm around the same time.[2]

William Sanford Perry was born in Goshen, New York, United States. In 1957, he was signed for an unprecedented five-album deal with the Pointblank/Virgin label.[3] The Bill Perry Blues Band consisted of Bill Perry (lead vocals, lead guitar), John Reddan (guitar and vocals), Tim Tindall (bass guitar) and Rob Curtis (drums). The band released a total of seven albums between 1995 and 2006.[1]

He died of a heart attack in Sugar Loaf, New York on July 17, 2007, at the age of 49.[1][4] He is survived by a son Aaron and a large family.

Roosevelt Sykes +17.07.1983

Roosevelt Sykes (* 31. Januar 1906 in Elmar, Arkansas; † 17. Juli 1983 in New Orleans, Louisiana) war ein einflussreicher US-amerikanischer Blues-Pianist, auch bekannt als „the Honeydripper“.

Mit 15 Jahren begann Sykes, Piano zu spielen. Anfang der 1920er zog die Familie nach St. Louis, wo Sykes bald als hervorragender Bluesmusiker bekannt wurde. Wie viele andere Musiker zog er herum und spielte vor einem ausschließlich männlichen Publikum in Sägewerken und Bauarbeitercamps entlang des Mississippi Rivers. Hier erarbeitete er sich ein Repertoire von rohen, sexuell anzüglichen Liedern. 1929 wurde er von einem Talentescout entdeckt und er machte seine erste Plattenaufnahme für Okeh Records. Es handelte sich um den 44 Blues, eine Nummer, die zu einem Bluesstandard und zu seinem Markenzeichen wurde. Er machte viele Aufnahmen für verschiedene Labels, auch unter Pseudonymen wie „Easy Papa Johnson“, „Dobby Bragg“ und „Willie Kelly“.

In den 1940ern ging Sykes nach Chicago; dort nahm er auch einige Singles für United auf. Er war einer der wenigen Musiker, die auch während des Krieges, in Zeiten der Rationierung, Aufnahmen machen durften. Sykes war einer der ersten amerikanischen Bluesmusiker, die in Europa auftraten. Nachdem der elektrifizierte Blues in Chicago das Musikgeschehen beherrschte, ging Sykes nach New Orleans. Dort begann er in den 1960er-Jahren wieder Platten aufzunehmen, so für Delmark, Bluesville, Storyville und Folkways.

Seine letzten Jahre verbrachte Roosevelt Sykes in New Orleans, wo er 1983 starb. 1999 wurde er in die Blues Hall of Fame aufgenommen.

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roosevelt_Sykes

Roosevelt Sykes (January 31, 1906 – July 17, 1983) was an American blues musician, also known as "The Honeydripper". He was a successful and prolific cigar-chomping blues piano player, whose rollicking thundering boogie-woogie was highly influential.[1]

Career

Born in Elmar, Arkansas, Sykes grew up near Helena but at age 15, went on the road playing piano with a barrelhouse style of blues. Like many bluesmen of his time, he travelled around playing to all-male audiences in sawmill, turpentine and levee camps along the Mississippi River, gathering a repertoire of raw, sexually explicit material. His wanderings eventually brought him to St. Louis, Missouri, where he met St. Louis Jimmy Oden.,[2] author of the blues standard "Goin' Down Slow".

In 1929 he was spotted by a talent scout and sent to New York City to record for Okeh Records.[3] His first release was "'44' Blues" which became a blues standard and his trademark.[3] He quickly began recording for multiple labels under various names including Easy Papa Johnson, Dobby Bragg and Willie Kelly. After he and Oden moved to Chicago he found his first period of fame when he signed with Decca Records in 1934.[3] In 1943, he signed with Bluebird Records and recorded with The Honeydrippers.[4] Sykes and Oden continued their musical friendship well into the 60s.

In Chicago, Sykes began to display an increasing urbanity in his lyric-writing, using an eight-bar blues pop gospel structure instead of the traditional twelve-bar blues. However, despite the growing urbanity of his outlook, he gradually became less competitive in the post-World War II music scene. After his RCA Victor contract expired, he continued to record for smaller labels, such as United, until his opportunities ran out in the mid-1950s.[3]

Roosevelt left Chicago in 1954 for New Orleans as electric blues was taking over the Chicago blues clubs. When he returned to recording in the 1960s it was for labels such as Delmark, Bluesville, Storyville and Folkways that were documenting the quickly passing blues history.[5] He lived out his final years in New Orleans, where he died from a heart attack[6] on July 17, 1983.[1]

Legacy

Sykes had a long career spanning the pre-war and postwar eras. His pounding piano boogies and risqué lyrics characterize his contributions to the blues. He was responsible for influential blues songs such as "44 Blues", "Driving Wheel", and "Night Time Is the Right Time".[1]

He was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1999[7] and the Gennett Records Walk of Fame in 2011.

Career

Born in Elmar, Arkansas, Sykes grew up near Helena but at age 15, went on the road playing piano with a barrelhouse style of blues. Like many bluesmen of his time, he travelled around playing to all-male audiences in sawmill, turpentine and levee camps along the Mississippi River, gathering a repertoire of raw, sexually explicit material. His wanderings eventually brought him to St. Louis, Missouri, where he met St. Louis Jimmy Oden.,[2] author of the blues standard "Goin' Down Slow".

In 1929 he was spotted by a talent scout and sent to New York City to record for Okeh Records.[3] His first release was "'44' Blues" which became a blues standard and his trademark.[3] He quickly began recording for multiple labels under various names including Easy Papa Johnson, Dobby Bragg and Willie Kelly. After he and Oden moved to Chicago he found his first period of fame when he signed with Decca Records in 1934.[3] In 1943, he signed with Bluebird Records and recorded with The Honeydrippers.[4] Sykes and Oden continued their musical friendship well into the 60s.

In Chicago, Sykes began to display an increasing urbanity in his lyric-writing, using an eight-bar blues pop gospel structure instead of the traditional twelve-bar blues. However, despite the growing urbanity of his outlook, he gradually became less competitive in the post-World War II music scene. After his RCA Victor contract expired, he continued to record for smaller labels, such as United, until his opportunities ran out in the mid-1950s.[3]

Roosevelt left Chicago in 1954 for New Orleans as electric blues was taking over the Chicago blues clubs. When he returned to recording in the 1960s it was for labels such as Delmark, Bluesville, Storyville and Folkways that were documenting the quickly passing blues history.[5] He lived out his final years in New Orleans, where he died from a heart attack[6] on July 17, 1983.[1]

Legacy

Sykes had a long career spanning the pre-war and postwar eras. His pounding piano boogies and risqué lyrics characterize his contributions to the blues. He was responsible for influential blues songs such as "44 Blues", "Driving Wheel", and "Night Time Is the Right Time".[1]

He was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 1999[7] and the Gennett Records Walk of Fame in 2011.

Roosevelt Sykes Sings The Blues (1962)

01. Slave For Your Love (2:06)

02. Gone With The Wind (2:59)

03. Wild Side (2:22)

04. Out On A Limb (3:19)

05. Honey Child (2:27)

06. Never Loved Like This Before (2:32)

07. Last Chance (2:45)

08. Casual Friend (2:32)

09. Your Will Is Mine (2:46)

10. Hupe Dupe Do (1:53)

02. Gone With The Wind (2:59)

03. Wild Side (2:22)

04. Out On A Limb (3:19)

05. Honey Child (2:27)

06. Never Loved Like This Before (2:32)

07. Last Chance (2:45)

08. Casual Friend (2:32)

09. Your Will Is Mine (2:46)

10. Hupe Dupe Do (1:53)

Sam Myers +17.07.2006

Samuel Joseph Myers (* 19. Februar 1936 in Laurel, Mississippi; † 17. Juli 2006 in Dallas, Texas) war ein US-amerikanischer Blues-Musiker (Gesang, Mundharmonika, Schlagzeug) und Songschreiber.

Während seiner Schulzeit in Jackson, Mississippi, lernte Myers Trompete und Schlagzeug zu spielen. Mit einem Stipendium besuchte er 1949 die "American Conservatory School of Music" in Chicago. Nachts spielte er in den Clubs der South Side, wo er mit so bekannten Bluesmusikern wie Jimmy Rogers, Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Little Walter, Hound Dog Taylor, Junior Lockwood und Elmore James auftrat.

Bei Elmore James spielte Myers von 1952 bis zu dessen Tod 1963 Schlagzeug. 1956 schrieb er den Bluesklassiker Sleeping In The Ground, der später u.a. von Eric Clapton und Robert Cray neu eingespielt wurde.

Zwischen den frühen 1960ern und 1986 arbeitete Myers in der Gegend um Jackson und im Chitlin' Circuit. Mit Sylvia Embry und der Mississippi All-Stars Blues Band war er weltweit auf Tour.

Ab 1986 bis zu seinem Tod war Myers Sänger und Mundharmonikaspieler bei Anson Funderburgh & The Rockets. Sam Myers starb am 17. Juli 2006 an Kehlkopfkrebs.

Die Rockets gewannen insgesamt neun Handy Awards, darunter drei als "Band of the Year" und 2004 in der Kategorie "Best Traditional Album of the Year".

Für sein Solo-Album Coming From The Old School war Sam Myers 2005 in der Kategorie "Best Traditional Album of the Year" nominiert.

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sam_Myers

Sam Myers (February 19, 1936 – July 17, 2006)[1] was an American blues musician and songwriter. He appeared as an accompanist on dozens of recordings for blues artists over five decades. He began his career as a drummer for Elmore James, but was most famous as a blues vocalist and blues harp player. For nearly two decades he was the featured vocalist for Anson Funderburgh & The Rockets.

Biography

Samuel Joseph Myers[1] was born in Laurel, Mississippi. He acquired juvenile cataracts at age 7 and was left legally blind for the rest of his life despite corrective surgery. He could make out shapes and shadows, but could not read print at all; he was taught Braille.[2] Myers acquired an interest in music while a schoolboy in Jackson, Mississippi and became skilled enough at playing the trumpet and drums that he received a non-degree scholarship from the American Conservatory of Music (formerly named the American Conservatory School of Music) in Chicago. Myers attended school by day and at night frequented the nightclubs of the South Side, Chicago. There he met and was sitting in with Jimmy Rogers, Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf, Little Walter, Hound Dog Taylor, Robert Lockwood, Jr., and Elmore James. Myers played drums with Elmore James on a fairly steady basis from 1952 until James's death in 1963, and is credited on many of James's historic recordings for Chess Records. In 1956, Myers wrote and recorded what was to be his most famous single, "Sleeping In The Ground", a song that has been covered by Blind Faith, Eric Clapton, Robert Cray, and many other blues artists, as well as being featured on Bob Dylan's Theme Time Radio Hour show on 'Sleep'.

From the early 1960s until 1986, Myers worked the clubs in and around Jackson, as well as across the South in the (formerly) racially segregated string of venues dubbed the Chitlin' Circuit. He also toured the world with Sylvia Embry and the Mississippi All-Stars Blues Band.

In 1986, Myers met Anson Funderburgh, from Plano, Texas, and joined his band, The Rockets. Myers toured all over the U.S. and the world with The Rockets, enjoying a partnership that endured until the time of his death, from complications from throat cancer surgery on July 17, 2006, in Dallas, Texas.[1]

Just before Myers died, he toured as a solo artist, in Sweden, Norway and Denmark, with the Swedish band, Bloosblasters.[3]

That same year, the University Press of Mississippi published Myers' autobiography titled Sam Myers: The Blues is My Story. Writer Jeff Horton, whose work has appeared in Blues Revue and Southwest Blues, chronicled Myers' history and delved into his memories of life on the road.

Awards

Myers and The Rockets collectively won nine W. C. Handy Awards, including three "Band of the Year" awards and the 2004 award for Best Traditional Album of the Year. In 2005, Myers' record, Coming From The Old School was nominated for Traditional Blues Album of the Year for his .[4]

In January 2000, Myers was inducted into the Farish Street Walk of Fame in Jackson, Mississippi, an honor he shares with Dorothy Moore and Sonny Boy Williamson II. In 2006, just months before Myers died, the Governor of Mississippi presented Myers with the Governor's Award for Excellence in the Arts, and was named state Blues Ambassador by the Mississippi Arts Commission.

Biography

Samuel Joseph Myers[1] was born in Laurel, Mississippi. He acquired juvenile cataracts at age 7 and was left legally blind for the rest of his life despite corrective surgery. He could make out shapes and shadows, but could not read print at all; he was taught Braille.[2] Myers acquired an interest in music while a schoolboy in Jackson, Mississippi and became skilled enough at playing the trumpet and drums that he received a non-degree scholarship from the American Conservatory of Music (formerly named the American Conservatory School of Music) in Chicago. Myers attended school by day and at night frequented the nightclubs of the South Side, Chicago. There he met and was sitting in with Jimmy Rogers, Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf, Little Walter, Hound Dog Taylor, Robert Lockwood, Jr., and Elmore James. Myers played drums with Elmore James on a fairly steady basis from 1952 until James's death in 1963, and is credited on many of James's historic recordings for Chess Records. In 1956, Myers wrote and recorded what was to be his most famous single, "Sleeping In The Ground", a song that has been covered by Blind Faith, Eric Clapton, Robert Cray, and many other blues artists, as well as being featured on Bob Dylan's Theme Time Radio Hour show on 'Sleep'.

From the early 1960s until 1986, Myers worked the clubs in and around Jackson, as well as across the South in the (formerly) racially segregated string of venues dubbed the Chitlin' Circuit. He also toured the world with Sylvia Embry and the Mississippi All-Stars Blues Band.

In 1986, Myers met Anson Funderburgh, from Plano, Texas, and joined his band, The Rockets. Myers toured all over the U.S. and the world with The Rockets, enjoying a partnership that endured until the time of his death, from complications from throat cancer surgery on July 17, 2006, in Dallas, Texas.[1]

Just before Myers died, he toured as a solo artist, in Sweden, Norway and Denmark, with the Swedish band, Bloosblasters.[3]

That same year, the University Press of Mississippi published Myers' autobiography titled Sam Myers: The Blues is My Story. Writer Jeff Horton, whose work has appeared in Blues Revue and Southwest Blues, chronicled Myers' history and delved into his memories of life on the road.

Awards

Myers and The Rockets collectively won nine W. C. Handy Awards, including three "Band of the Year" awards and the 2004 award for Best Traditional Album of the Year. In 2005, Myers' record, Coming From The Old School was nominated for Traditional Blues Album of the Year for his .[4]

In January 2000, Myers was inducted into the Farish Street Walk of Fame in Jackson, Mississippi, an honor he shares with Dorothy Moore and Sonny Boy Williamson II. In 2006, just months before Myers died, the Governor of Mississippi presented Myers with the Governor's Award for Excellence in the Arts, and was named state Blues Ambassador by the Mississippi Arts Commission.

Billie Holiday +17.07.1959

Billie Holiday (* 7. April 1915 in Philadelphia[1]; † 17. Juli 1959 in New York; geboren als Elinore Harris[2]) zählt mit Ella Fitzgerald und Sarah Vaughan zu den bedeutendsten Jazzsängerinnen.

Kindheit (1915–1929)

Billie Holiday wurde vor der Annahme ihres Künstlernamens meist Eleanora Fagan genannt, auch wenn ihre Geburtsurkunde den Namen Elionora Harris aufweist. Später erhielt sie von ihrem Freund Lester Young den Spitznamen Lady Day.

Ein Großteil der Informationen über ihre Kindheit beruhen auf ihrer Autobiografie Lady Sings the Blues, die sie ab 1956 dem Journalisten William Dufty diktierte, deren Wahrheitsgehalt allerdings umstritten ist. Bereits der erste Satz deutet ihre ganz persönliche Sicht auf die Lebensumstände ihrer Kindheit an: „Mam und Dad waren noch Kinder, als sie heirateten. Er war achtzehn, sie war sechzehn, und ich war drei.“ Tatsächlich war ihre Mutter bei der Geburt der Tochter neunzehn Jahre alt, und sie war mit Billies vermutlichem[3] leiblichen Vater nie verheiratet und lebte mit ihm nie unter einem Dach.

Ihre Mutter Sarah „Sadie“ Fagan (geborene Harris) (1896–1945) behauptete, Clarence Halliday (1898–1937) alias: Clarence Holiday sei Billies leiblicher Vater, ein Jazz-Gitarrist, der später unter anderem im Fletcher Henderson Orchestra spielte. Nach Billies Geburt arbeitete sie eine Zeit lang als Serviererin in Zügen, weshalb Billie im Laufe ihrer ersten zehn Lebensjahre größtenteils bei der Schwiegermutter ihrer Halbschwester, Martha Miller, in Baltimore aufwuchs.[4] Als Billie elf Jahre alt war, eröffnete ihre Mutter das Restaurant The East Side Grill, in dem das Mädchen oft viele Stunden arbeiten musste. Kurze Zeit später brach sie die Schule ab.[5]

Am 24. Dezember 1926, Billie war elf Jahre alt, entdeckte ihre Mutter, als sie von der Arbeit zurückkam, wie ihr Nachbar, Wilbur Rich, gerade das Kind vergewaltigte.[6] Rich wurde verhaftet, und Billie kam „zu ihrem Schutz“ in das katholische Erziehungsheim The House of the Good Shepherd. Mit zwölf wurde Billie aus dem Erziehungsheim entlassen. Kurz darauf begann ihre Mutter, in einem Bordell zu arbeiten. Billie arbeitete dort ebenfalls als Botenmädchen. Hier lernte sie auf dem Grammophon des Etablissements die Musik von Louis Armstrong und Bessie Smith kennen. Nach ein paar Monaten wurden Mutter und Tochter während einer Razzia verhaftet. Danach zog die Mutter nach Harlem und ließ ihre Tochter abermals bei Martha Miller zurück.[7] Billie arbeitete damals vermutlich noch einige Zeit in einem Bordell in Baltimore als Prostituierte. In dieser Zeit begann sie mit dem Singen. Anfang 1929 folgte sie dann ihrer Mutter nach New York. Die dortige Vermieterin, Florence Williams, betrieb ein Bordell, in dem Mutter und die dreizehnjährige Tochter „für 5 $ pro Freier“ als Prostituierte arbeiteten.[8] Am 2. Mai 1929 kam es erneut zu einer Razzia, und wieder wurde Billie verhaftet und kam ins Gefängnis. Erst im Oktober desselben Jahres wurde sie wieder entlassen.

Die frühe Gesangskarriere (1929–1935)

1929 begann Elinore Harris in Clubs unter dem Namen aufzutreten, unter dem sie bekannt wurde: Billie Holiday. Er setzt sich zusammen aus dem Vornamen der Schauspielerin Billie Dove und dem Nachnamen ihres Vaters Clarence Holiday,[9] wobei sie ihren Nachnamen anfänglich noch Halliday schrieb.

1929–1931 trat sie zusammen mit ihrem Nachbarn, dem Tenorsaxofonisten Kenneth Hollan, in Clubs wie dem Grey Dawn, dem Pod’s and Jerry’s und dem Brooklyn Elks’ Club auf.[10]

Anfang 1933 wurde sie von den Plattenproduzenten John Hammond und Bernie Hanighen entdeckt, die von ihrem Improvisationstalent beeindruckt waren. Man organisierte im November 1933 Aufnahmen mit Benny Goodman für die Achtzehnjährige. Sie nahmen die Songs Your Mother’s Son-In-Law und Riffin’ the Scotch auf; Letzterer wurde mit einer Auflage von 5.000 Stück Billie Holidays erster Hit.

1935 sang sie Saddest Tale in Duke Ellingtons Symphony in Black: A Rhapsody of Negro Life.

Teddy Wilson (1935–1938)

Im gleichen Jahr nahm Hammond die aufstrebende Künstlerin für Brunswick Records unter Vertrag. Hier nahm sie bekannte Stücke im neu aufkommenden Swing-Stil für die immer populärer werdenden Jukeboxes auf. Holiday konnte bei diesen Aufnahmen frei improvisieren und erfand dabei jenen einzigartigen, höchst eigenwilligen Stil, mit den Melodien frei zu spielen, der zu ihrem Markenzeichen werden sollte. Zu ihren Aufnahmen aus der ersten Session gehörten What a Little Moonlight Can Do und Miss Brown to You, zwei Titel, die der Plattenfirma anfangs nicht besonders zusagten. Doch als die Platten erfolgreich verkauft wurden, begann man auch Platten unter ihrem eigenen Namen zu produzieren.[11] Wilson und Holiday nahmen viele populäre Songs der damaligen Zeit auf und machten sie damit zu Jazzklassikern. Stephan Richter schreibt hierzu: (…) in Wahrheit lebten in Holidays Liedern nicht die Komponisten auf, sondern ihre Stimme, ihre Persönlichkeit, die jedes Wort zu ihrem eigenen macht, jede Textzeile in ihrem Sinn neu schreibt.[12]

An vielen dieser Aufnahmen wirkte auch Lester Young mit, mit dem sie fortan eine lebenslange Freundschaft verbinden sollte. Er gab ihr den Spitznamen Lady Day, sie nannte ihn Prez. Außerdem meinte Young, ihre Mutter sollte den Spitznamen The Duchess („Die Herzogin“) erhalten, wenn ihre Tochter Lady heißt.

Da die Lieder nicht aufwendig arrangiert, sondern über weite Teile improvisiert wurden, waren diese Aufnahmen für Brunswick nicht teuer. Holiday bekam dafür eine Einmalzahlung und erhielt keinerlei Geld aus den Plattenverkäufen und Radioaufführungen, obwohl sich Aufnahmen wie I Cried for You 15.000 Mal und mehr verkauften, was ungefähr das Fünffache sonstiger Brunswick-Platten ausmachte.[13]

Count Basie und Artie Shaw (1937–1938)

Als Nächstes sang sie bei Count Basie. Er gewöhnte sich schnell daran, dass Billie starken Einfluss auf die Melodiefindung nahm, denn sie wusste schon damals genau, wie ihr Gesang klingen sollte.[14] Auch wenn sie nie mit Basie ins Studio ging – es gibt nur die Liveaufnahme I Can’t Get Started, They Can’t Take That Away from Me und Swing It Brother Swing aus der Zeit – so nahm sie doch viele seiner Musiker mit ins Studio zu Aufnahmen mit Teddy Wilson.[15] Im Februar 1938 kam es zum Bruch; laut Billie Holiday wegen eines Streits über zu niedrige Bezahlung und Änderungswünsche an ihrem Gesangsstil, laut Basie aufgrund ihrer Unzuverlässigkeit.[16]

Danach sang sie bei Artie Shaw, der bereits im März 1936 ihre erste Radioübertragung beim Sender WABC organisiert hatte. Aufgrund des großen Erfolgs der Sendung ließ ABC im April eine Sondersendung folgen. Da Shaw weniger Gesangsstücke im Programm hatte als Basie, konnte Holiday bei ihm weniger singen. Außerdem übte das Management Druck auf den Bandleader aus, lieber die weiße Sängerin Nita Bradley zu beschäftigen, mit der sie sich nicht sehr gut verstand. Als sie im November 1938 im Lincoln Hotel aufgrund von Beschwerden des Hotelmanagements gezwungen wurde, den Lastenaufzug und den Hinterausgang zu benutzen, war das Maß voll, und sie entschloss sich, die Band zu verlassen. Die einzige erhaltene Aufnahme aus dieser Zeit ist Any Old Time.

Sie trat als eine der ersten Jazzsängerinnen mit weißen Musikern auf und überwand damit rassistische Grenzen. Trotz dieser Vorreiterrolle wurde sie weiterhin gezwungen, Hintereingänge zu benutzen. Sie berichtete später, dass sie in dunklen, abgelegenen Räumen auf ihre Auftritte warten musste. Auf der Bühne verwandelte sie sich in Lady Day mit der weißen Gardenie im Haar. Die tiefe emotionale Wirkung ihres Gesangs erklärte sie mit der Bemerkung: „Ich habe diese Songs gelebt“.

Billie Holiday litt unter ihrer Diskriminierung als Schwarze. Vor allem bei den Tourneen mit gemischten Bands wie der von Artie Shaw 1938 machten sie und die anderen schwarzen Musiker täglich entwürdigende Erfahrungen. Als besonders demütigend empfand sie Auftritte, für die ihr Gesicht mit Make-up geschwärzt wurde, da dem weißen Publikum angeblich Billie Holidays Teint zuweilen als zu hell erschien.

Trotz aller Schwierigkeiten wurde 1938 ein sehr erfolgreiches Jahr für die Sängerin; im September erreichte ihre Aufnahme I’m Gonna Lock My Heart Platz 6 in den Charts.

Mainstream-Erfolg (1939–1947)

1939 sang sie erstmals den Song Strange Fruit, der auf dem gleichnamigen Gedicht des jüdischen Lehrers Abel Meeropol (alias Lewis Allan) basiert und eindringlich die Lynchjustiz an Schwarzen thematisiert. Während die Produzenten von Columbia das Thema „zu heiß“ fanden, erklärte Commodore Records sich bereit, es aufzunehmen, und die Platte wurde einer ihrer größten Erfolge. Seither verband das Publikum Billie Holiday mit diesem Stück und wollte es immer wieder von ihr hören. Die Aufführungen im Café Society waren minutiös inszeniert; Bevor sie das Stück sang, ließ sie das Publikum vorher von den Kellnern um Ruhe bitten. Das Licht wurde während des langen Intros heruntergedimmt und ein einziger Scheinwerfer erhellte Billie Holidays Gesicht. Mit dem Verklingen des letzten Tons erlosch das Licht, worauf sie dann im Dunkeln verschwand.[17]

Billie Holiday war ein Star geworden. Ihre Mutter Sadie Fagan nannte ihr Restaurant jetzt Mom Holiday. Gleichzeitig verspielte sie das Geld ihrer Tochter beim Würfeln. Als Billie Holiday eines Abends Geld von ihr haben wollte, zeigte ihre Mutter ihr die kalte Schulter. Angeblich verließ Billie Holiday daraufhin fluchend das Restaurant und rief: God bless the child that’s got its own!, woraus später die Titelzeile des Liedes God Bless the Child werden sollte. Der Song erreichte Platz 3 in den Billboards des Jahres und verkaufte sich über eine Million Mal.[18]

1943 schrieb das Life Magazine über Billie Holiday, sie besitze den individuellsten Stil aller populären Sängerinnen und werde damit von vielen kopiert.[19]

Bevor sie 1944 Lover Man für Decca aufnahm, flehte sie ihren Produzenten Milt Gabler an, wie Ella Fitzgerald und Frank Sinatra Streicher für die Aufnahme zu bekommen. Als sie dann am 4. Oktober ins Studio kam, war sie zu Tränen gerührt, weil dort tatsächlich ein Streicherensemble sie erwartete. Von da an wurde ihre Stimme häufiger von Streichern untermalt.[20]

Einen weiteren Erfolg erlebte Holiday, als sie 1944 in der Metropolitan Opera in New York als erste Jazz-Sängerin gefeiert wurde.

Der Auftritt im Film New Orleans (1946) neben ihrem Vorbild Louis Armstrong war für sie und ihre Fans hingegen enttäuschend. Sie durfte nur eine solche Rolle spielen, wie sie Hollywood damals für Schwarze meistens vorgesehen hatte, nämlich das „Dienstmädchen“. Billie, die glaubte, sich selbst spielen zu dürfen, war maßlos enttäuscht. Während der Dreharbeiten ließ sich außerdem ein Problem nicht mehr verbergen, das sie schon seit den frühen 1940er Jahren begleitete: ihre Heroinsucht. Joe Guy, ihr Ehemann und Dealer, erhielt deshalb Set-Verbot.[21]

Carnegie Hall, Prozess wegen Drogenbesitzes (1947–1949)

Am 16. Mai 1947 wurde Billie Holiday wegen Drogenbesitzes verhaftet. Im darauffolgenden Prozess bekannte sie sich schuldig und bat darum, in ein Krankenhaus eingewiesen zu werden, nachdem ihr Anwalt ihr hatte ausrichten lassen, er habe keine Lust, sie in dem Verfahren zu vertreten.[22] Sie erhielt eine Gefängnisstrafe, kam ins Alderson Federal Prison Camp in West Virginia und wurde am 16. März 1948 wegen guter Führung vorzeitig entlassen. Ihr Manager Ed Fishman wollte daraufhin ein Konzert in der Carnegie Hall veranstalten, doch Holiday zögerte, da sie nicht wusste, ob das Publikum nach ihrer Verhaftung noch zu ihr stehen würde. Schließlich gab sie nach. Das ausverkaufte Konzert vom 27. März 1948 wurde zu einem beispiellosen Erfolg.

Aufgrund ihrer Vorstrafe hatte Holiday ihre Cabaret-Lizenz verloren und durfte nicht an Orten mit Alkoholausschanklizenz auftreten, was ihr Einkommen erheblich minderte, zumal sie immer noch nicht angemessen an den Lizenzen beteiligt wurde (1958 erhielt sie einen Scheck über 11 Dollar für Lizenzgebühren).[23]

Am 22. Januar 1949 wurde sie erneut wegen Drogenbesitzes festgenommen.

Die letzten Jahre (1950–1959)

Mit den 1950er Jahren begann ihr gesundheitlicher Abstieg. Weiterhin hatte sie Beziehungen mit gewalttätigen Männern, Entzugsversuche blieben erfolglos. Der Drogenkonsum wirkte sich auch auf ihre Stimme aus: In ihren späteren Aufnahmen bei Verve Records weicht ihr jugendlicher Elan zusehends einer merklichen Schwermut.

1956 erschien ihre Autobiografie Lady Sings the Blues. Die gleichnamige LP enthielt bis auf den Titelsong keine neuen Aufnahmen, wurde jedoch vom Billboard Magazine als „würdige musikalische Ergänzung ihrer Autobiografie“ gelobt.[24]

Im November dieses Jahres hatte sie ihre letzten beiden ausverkauften Konzerte in der Carnegie Hall, was für jeden Künstler eine große Auszeichnung ist, besonders jedoch für eine schwarze Sängerin in den späten 1950er Jahren. 13 Aufnahmen aus dem zweiten Konzert erschienen 1961 postum auf dem Album The Essential Billie Holiday – Carnegie Hall Concert. Gilbert Milstein von der New York Times schrieb dazu in seinem Covertext:

„Die Probe war zusammenhangslos, ihre Stimme klang dünn und schleppend, ihr Körper müde gebeugt. Aber ich werde niemals die Metamorphose an diesem Abend vergessen. Das Licht erlosch, die Musiker begannen zu spielen und die Erzählung begann. Miss Holiday trat zwischen den Vorhängen hervor in das sie erwartende Scheinwerferlicht, in eine weiße Robe gehüllt und mit einer weißen Gardenie im schwarzen Haar. Aufrecht und schön, souverän und lächelnd. Und als sie den ersten Teil ihrer Erzählung beendet hatte, begann sie zu singen – mit unverminderter Kraft – mit all ihrer Kunst. Ich war sehr bewegt. Mein Gesicht und meine Augen brannten in der Dunkelheit. Und ich erinnere mich an eine Sache. Ich lächelte.“

Tod

Anfang 1959 fand ihr Arzt heraus, dass sie unter Leberzirrhose litt, und verbot ihr das Trinken. Nach kurzer Abstinenz trank sie allerdings weiter. Im Mai hatte sie zehn Kilogramm Gewicht verloren. Am 31. Mai 1959 wurde sie ins Metropolitan Hospital eingeliefert, wo sie unter entwürdigenden Umständen starb; Polizisten standen um das Krankenbett herum, um sie wegen Drogenbesitzes zu verhaften.

Als sie starb, hatte sie 0,70 US-Dollar auf dem Konto.[25]

Holiday wurde auf dem Saint Raymonds Cemetery in der Bronx bestattet.

Würdigungen

Billie Holiday wurde in die Blues Hall of Fame und auf dem Hollywood Walk of Fame aufgenommen.

Bekannte Beziehungen

Orson Welles (Schauspieler/Regisseur)[26] [27]

Tallulah Bankhead (Schauspielerin)[28] [29] [30]

John Levy

Jimmy Monroe, Ehemann, Hochzeit am 25. August 1941, geschieden 1947

Joe Guy, Ehemann nach common law, getrennt 1957 (Trompeter und Drogendealer)

Louis McKay, Ehemann nach common law, Hochzeit am 28. März 1957, bis zu ihrem

Tod.[31]

Einfluss

Holiday hatte in allen Phasen ihrer Karriere einen großen Einfluss auf andere Künstler. Nach ihrem Tod beeinflusste sie Sängerinnen wie Janis Joplin und Nina Simone.

Ihre späten Aufnahmen für das Schallplattenlabel Verve, darunter Solitude 1952 und Music for Torching 1955, haben genauso überlebt wie jene früheren Aufnahmen, die von 1933 an für Columbia Records, Commodore (The Complete Commodore Recordings) und Decca Records entstanden. Viele ihrer Stücke, unter anderem God Bless the Child, George Gershwins I Loves You Porgy und ihr reuevoller Blues Fine and Mellow sind Jazzklassiker geworden.

Billie Holiday besaß eine unverwechselbare Stimme. Obwohl sie keine musikalische Ausbildung hatte und nur über einen begrenzten Stimmumfang verfügte, war sie eine außergewöhnliche Sängerin; zugleich herb und zerbrechlich, sowohl unterkühlt als auch leidenschaftlich.

„Bei Holiday gerät man in einen existentiellen Strudel, ein wirkliches Einlassen auf diese Musik schaltet das Gehirn aus wie eine Droge. Nur mit größten Schwierigkeiten wird man sich zu einem analytischen Hören dieser Lieder zwingen können, Holidays Stimme allein greift direkt an die Nervenbahnen.“

– Stephan Richter[32]

Einige der bekanntesten Standards, die sie mit ihrer Interpretation geprägt hat, sind A Fine Romance, All of Me, As Time Goes By, Autumn in New York, But Beautiful, Do You Know What It Means, Embraceable You, Fine and Mellow (Billie Holiday 1939), Gloomy Sunday, God Bless the Child (Billie Holiday 1939), Good Morning Heartache, I Cover the Waterfront, I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues, I Loves You Porgy, It’s Easy to Remember (And So Hard to Forget), Yesterdays, Lover Come Back to Me, Love for Sale, Lover Man, The Man I Love, Mean to Me, Nice Work If You Can Get It, Night and Day, Solitude, Stormy Weather, Summertime, There Is No Greater Love, These Foolish Things (Remind Me of You), The Way You Look Tonight und Willow Weep for Me.

Filme

Das Leben von Billie Holiday wurde 1972 unter dem Titel Lady Sings the Blues verfilmt. Die Hauptrolle spielte die amerikanische Soul-Sängerin Diana Ross, die für ihre Rolle für den Oscar als beste Schauspielerin nominiert wurde.

Billie Holiday forever. Dokumentarfilm, Frankreich, 2012, 52:40 Min., Buch und Regie: Frank Cassenti, Produktion: arte France, Oléo Films, Erstsendung: 12. Dezember 2012 bei arte, Inhaltsangabe von arte.