1929 Louis Myers*

1945 Blind Willie Johnson+

1966 Will Shade+

1970 Jimi Henderix+

1970 Maxwell Davis+

1983 Roy Milton+

1995 Malte Wollenburg*

1997 Jimmy Witherspoon+

Mick Martin*

Tommy Schneller*

Paul Olsen*

Happy Birthday

Louis Myers *18.09.1929

Louis Myers (* 18. September 1929 in Byhalia, Mississippi; † 5. September 1994 in Chicago, Illinois) war ein US-amerikanischer Bluesmusiker (Gitarre, Mundharmonika), der vor allem als Mitglied der Band The Aces bekannt wurde.

Wie sein Bruder Dave kam Louis Myers 1941 mit der Familie aus Mississippi nach Chicago. Beide lernten durch Lonnie Johnson den Chicago Blues kennen, nachdem sie zuvor bereits von ihrem Vater Amos Myers gelernt hatten, den Country Blues auf der Gitarre zu spielen. Als Teenager trat Louis trat mit Bluesmusikern wie Othum Brown und Arthur „Big Boy“ Spires auf.[1]

Mit seinem Bruder Dave (Gitarre, Mundharmonika) bildete Louis das Duo „The Little Boys“. Dave spielte auf seiner E-Gitarre den Rhythmus, während Louis die Leadgitarre spielte. Zusammen mit Junior Wells (Mundharmonika) und Fred Below (Schlagzeug) entstanden daraus schließlich „The Aces“. Mit Little Walter anstelle von Wells spielten sie bis Mitte der 1950er als „Little Walter & His Jukes“ eine ganze Reihe von Hits ein.[2]

1954 verließ Louis die Band, um als Sessionmusiker zu arbeiten. In den 1970ern gingen die Myers-Brüder wieder als „The Aces“ auf Tour. 1978 brachte Louis mit I'm a Southern Man sein erstes Album unter eigenem Namen heraus. Während der Aufnahmen zu seinem letzten Album, Tell My Story Movin’, erlitt Louis Myers 1991 einen Schlaganfall. Er starb am 5. September 1994 in Chicago.

Wie sein Bruder Dave kam Louis Myers 1941 mit der Familie aus Mississippi nach Chicago. Beide lernten durch Lonnie Johnson den Chicago Blues kennen, nachdem sie zuvor bereits von ihrem Vater Amos Myers gelernt hatten, den Country Blues auf der Gitarre zu spielen. Als Teenager trat Louis trat mit Bluesmusikern wie Othum Brown und Arthur „Big Boy“ Spires auf.[1]

Mit seinem Bruder Dave (Gitarre, Mundharmonika) bildete Louis das Duo „The Little Boys“. Dave spielte auf seiner E-Gitarre den Rhythmus, während Louis die Leadgitarre spielte. Zusammen mit Junior Wells (Mundharmonika) und Fred Below (Schlagzeug) entstanden daraus schließlich „The Aces“. Mit Little Walter anstelle von Wells spielten sie bis Mitte der 1950er als „Little Walter & His Jukes“ eine ganze Reihe von Hits ein.[2]

1954 verließ Louis die Band, um als Sessionmusiker zu arbeiten. In den 1970ern gingen die Myers-Brüder wieder als „The Aces“ auf Tour. 1978 brachte Louis mit I'm a Southern Man sein erstes Album unter eigenem Namen heraus. Während der Aufnahmen zu seinem letzten Album, Tell My Story Movin’, erlitt Louis Myers 1991 einen Schlaganfall. Er starb am 5. September 1994 in Chicago.

Though he was certainly capable of brilliantly fronting a band, remarkably versatile guitarist/harpist Louis Myers will forever be recognized first and foremost as a top-drawer sideman and founding member of the Aces -- the band that backed harmonica wizard Little Walter on his immortal early Checker waxings.

Along with his older brother David -- another charter member of the Aces -- Louis left Mississippi for Chicago with his family in 1941. Fate saw that the family move next door to blues great Lonnie Johnson, whose complex riffs caught young Louis' ear. Another Myers brother, harp-blowing Bob, hooked Louis up with guitarist Othum Brown for house party gigs. Myers also played with guitarist Arthur "Big Boy" Spires before teaming with his brother, David, on guitar and young harpist Junior Wells, to form the first incarnation of the Aces (who were initially known as the Three Deuces). In 1950, drummer Fred Below came on board.

In effect, the Aces and Muddy Waters traded harpists in 1952, Wells leaving to play with Waters while Little Walter, just breaking nationally with his classic "Juke," moved into the frontman role with the Aces. Myers and the Aces backed Walter on his seminal "Mean Old World," "Sad Hours," "Off the Wall," and "Tell Me Mama" and at New York's famous Apollo Theater before Louis left in 1954 (he and the Aces moonlighted on Wells' indispensable 1953-1954 output for States).

Plenty of sideman work awaited Myers -- he played with Otis Rush, Earl Hooker, and many more. But his own recording career was practically non-existent; after a solitary 1956 single for Abco, "Just Whaling"/"Bluesy," that found Myers blowing harp in Walter-like style, it wasn't until 1968 that two Myers tracks turned up on Delmark.

I'm a Southern Man

the Aces re-formed during the '70s and visited Europe often as a trusty rhythm section for touring acts. Myers cut a fine set for Advent in 1978, I'm a Southern Man, that showed just how effective he could be as a leader (in front of an L.A. band, no less). Myers was hampered by the effects of a stroke while recording his last album for Earwig, 1991's Tell My Story Movin'. He courageously completed the disc but was limited to playing harp only. His health soon took a turn for the worse, ending his distinguished musical career.

Along with his older brother David -- another charter member of the Aces -- Louis left Mississippi for Chicago with his family in 1941. Fate saw that the family move next door to blues great Lonnie Johnson, whose complex riffs caught young Louis' ear. Another Myers brother, harp-blowing Bob, hooked Louis up with guitarist Othum Brown for house party gigs. Myers also played with guitarist Arthur "Big Boy" Spires before teaming with his brother, David, on guitar and young harpist Junior Wells, to form the first incarnation of the Aces (who were initially known as the Three Deuces). In 1950, drummer Fred Below came on board.

In effect, the Aces and Muddy Waters traded harpists in 1952, Wells leaving to play with Waters while Little Walter, just breaking nationally with his classic "Juke," moved into the frontman role with the Aces. Myers and the Aces backed Walter on his seminal "Mean Old World," "Sad Hours," "Off the Wall," and "Tell Me Mama" and at New York's famous Apollo Theater before Louis left in 1954 (he and the Aces moonlighted on Wells' indispensable 1953-1954 output for States).

Plenty of sideman work awaited Myers -- he played with Otis Rush, Earl Hooker, and many more. But his own recording career was practically non-existent; after a solitary 1956 single for Abco, "Just Whaling"/"Bluesy," that found Myers blowing harp in Walter-like style, it wasn't until 1968 that two Myers tracks turned up on Delmark.

I'm a Southern Man

the Aces re-formed during the '70s and visited Europe often as a trusty rhythm section for touring acts. Myers cut a fine set for Advent in 1978, I'm a Southern Man, that showed just how effective he could be as a leader (in front of an L.A. band, no less). Myers was hampered by the effects of a stroke while recording his last album for Earwig, 1991's Tell My Story Movin'. He courageously completed the disc but was limited to playing harp only. His health soon took a turn for the worse, ending his distinguished musical career.

Mick Martin *18.09.

The only member of the original Crawdad line up, Mick’s career has spanned more than three decades & a multitude of musical styles. An award winning guitarist whose past band efforts include mid 80’s Pop/Rock act Idol Minds, The Country Boys & The Blue Heeler Band, as well as years of supporting/backing international stars including Nick Lowe, Joe Walsh (from the Eagles) Johnny Tillotson & local heroes such as Col Elliot, Jackie Love, Adam Harvey, Lee & Tania Kernaghan, Peter Cupples, Little Pattie, Normie Rowe, Barry Crocker, Judie Stone, Paul Martell, Jane Scali, The Drifters, Ian Turpie, Bev Harrell & Slim Dusty just to name a few. Better known to the rest of the band as “Captain Craw”, Mick thrives on playing with great musicians & loves this line up. “We’re keeping it great without sacrificing the fun aspect of the live performances”.

Tommy Schneller *18.09.

Er kennt die Festivals in Europa und die kleinen Clubs auf der Beale Street in Memphis - Tommy

Schneller ist auf den großen Bühnen dieser Welt zuhause. Sein charmanter, unverwechselbarerGesang und sein erdig warmer Saxophonsound haben ihn in den vergangenen Jahren zu einem der

beliebtesten Musiker Europas gemacht. Schneller wurde drei Mal mit dem German Blues Award

(2010, 2012, 2014) sowie dem Preis der Deutschen Schallplattenkritik (2011) ausgezeichnet.

Tommy Schnellers Band beinhaltet mehrere Attribute, die keine andere Band dieses Genre in

Deutschland hat: Für eine siebenköpfige Band ist sie soundmäßig sehr kompakt, hier wirkt niemals

ein Song überladen oder fahrig, wie man es bei der Besetzung bei vielen anderen Bands oft nach ein

paar Titeln feststellt. Die Musik hat einen authentischen US-touch, ist frisch und lebt von Tommys

wiedererkennbarer Stimme und natürlich von seinem unverkennbarem Saxophonsound. Blues-Soul

mit viel Druck, Tanzbarkeit und voller Groove. Eine hoch attraktive und, last but not least, eine dazu

sehr sympathische Band.

http://tommyschneller.de/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Backbeat-press.pdf

Tommy Schneller (* 18. September 1969 in Ankum bei Osnabrück) ist ein deutscher Bluesmusiker, Saxophonist und Sänger. Neben der Arbeit in seiner eigenen Band ist er immer wieder Gastmusiker in diversen anderen Formationen. Sein Album „Smiling for a Reason“ gewann 2012 den Vierteljahrespreis der Deutschen Schallplattenkritik[1].

Musikalischer Werdegang

Im Alter von fünf unternahm Tommy Schneller erste kreative Schritte im Rahmen der musikalischen Früherziehung am Osnabrücker Konservatorium, im Grundschulalter folgte Geigenunterricht. Über seinen Lehrer Hans Schwach, der Klarinettist beim Osnabrücker Sinfonieorchester war, lernte er alte Swing-Aufnahmen kennen: etwa von Louis Jordan, Count Basie, Duke Ellington und Satchmo[2]. Tommy Schneller wechselte das Instrument zum Saxophon und wurde Mitglied in der Big-Band seiner Schule. Als „musikalisches Schlüsselerlebnis“[2] bezeichnet Tommy Schneller ein Konzert des Pianisten Little Willie Littlefield, das er 1986 im Osnabrücker Blues Club Pink Piano sah und das mit einer vierhändigen Improvisation zusammen mit Christian Rannenberg endete, in die letztendlich Saxofonist Gary Wiggins einstieg. Letzterer lebte in der Nachbarschaft des damals 16-Jährigen und wurde sein Mentor, mit dem er bei Sessions erste Liveerfahrungen sammelte. 1989 folgte die erste feste Bandbesetzung Tommy Schnellers bei Christian Bleimings Boogie Boys. Gleichzeitig etablierte er sich auch als Sänger. Weitere Engagements für Al Jones und Tom Vieth folgten und begründeten die Profimusiker-Laufbahn des Saxophonisten. In den 1990ern zog Tommy Schneller nach Köln und wurde Mitglied von Richard Bargels Talkin’ Blues Combo. 1995 kam es mit der First Class Bluesband zur Zusammenarbeit mit Frank Biner. Dort spielte er erstmals auch mit Kevin Duvernay (Bass) und Tommie Harris (Drums), die später in seiner ersten eigenen Band die Rhythmussektion bildeten. In Deutschland war der gelernte Kaufmann Tommy Schneller kurzzeitig bei der Frankfurter Konzertagentur Lynro Music als Booker, Veranstaltungsassistent und Tourmanager tätig. Zu seinen Klienten zählten etwa Sweets Edison, Red Holloway und Ed Thigpen; mit ihnen stand der Saxophonist auch teilweise auf der Bühne. Des Weiteren war er als Roadmanager für John Hendrix, Clark Terry und Ray Brown tätig. In Zusammenarbeit mit der Bluesnight Band sowie der Grand Jam Band arbeitete Tommy Schneller seit 2000 mit diversen Größen aus der Bluesszene zusammen – darunter Larry Garner, Andreas Schmidt-Martelle, Rolf Stahlhofen und Ron Williams[2].

Eigene Projekte

Zurück in Osnabrück gründete Tommy Schneller zusammen mit dem Bassisten Olli Geselbracht das Label „Out Of Space“ und nahm im Februar 1997 seine erste Solo CD „Blown Away“ auf. Es folgten weitere Veröffentlichungen als Tommy Schneller Band und Bluesin’ the Groove, einem Projekt, das er zusammen mit Christian Rannenberg und Alex Lex 2010 etablierte. Zudem ist er ein gefragter Studiomusiker. Tommy Schneller nahm unter anderem mit Gregor Hilden, Supercharge und Henrik Freischlader auf. Letzterer zeichnete auch als Produzent seines Albums „Smiling for a Reason“ (2011) verantwortlich, das mit dem Vierteljahrespreis der Deutschen Schallplattenkritik ausgezeichnet wurde.

Tommy Schneller Band

Zur Tommy Schneller Band gehören als feste Besetzung noch Jens Filser (Gitarre, Gesang), Gregory Barrett (Keyboard, Gesang), Gary Winters (Trompete, Flügelhorn, Gesang), Dieter Kuhlmann (Trombone, Saxophon), Bernhard Weichinger (Schlagzeug, Gesang) und Maik Reishaus (Bass, Gesang).[3]

Neben eigenen Stücken von Tommy Schneller spielt die Band Klassiker aus den Bereichen Blues, Funk und Soul.

Musikalischer Werdegang

Im Alter von fünf unternahm Tommy Schneller erste kreative Schritte im Rahmen der musikalischen Früherziehung am Osnabrücker Konservatorium, im Grundschulalter folgte Geigenunterricht. Über seinen Lehrer Hans Schwach, der Klarinettist beim Osnabrücker Sinfonieorchester war, lernte er alte Swing-Aufnahmen kennen: etwa von Louis Jordan, Count Basie, Duke Ellington und Satchmo[2]. Tommy Schneller wechselte das Instrument zum Saxophon und wurde Mitglied in der Big-Band seiner Schule. Als „musikalisches Schlüsselerlebnis“[2] bezeichnet Tommy Schneller ein Konzert des Pianisten Little Willie Littlefield, das er 1986 im Osnabrücker Blues Club Pink Piano sah und das mit einer vierhändigen Improvisation zusammen mit Christian Rannenberg endete, in die letztendlich Saxofonist Gary Wiggins einstieg. Letzterer lebte in der Nachbarschaft des damals 16-Jährigen und wurde sein Mentor, mit dem er bei Sessions erste Liveerfahrungen sammelte. 1989 folgte die erste feste Bandbesetzung Tommy Schnellers bei Christian Bleimings Boogie Boys. Gleichzeitig etablierte er sich auch als Sänger. Weitere Engagements für Al Jones und Tom Vieth folgten und begründeten die Profimusiker-Laufbahn des Saxophonisten. In den 1990ern zog Tommy Schneller nach Köln und wurde Mitglied von Richard Bargels Talkin’ Blues Combo. 1995 kam es mit der First Class Bluesband zur Zusammenarbeit mit Frank Biner. Dort spielte er erstmals auch mit Kevin Duvernay (Bass) und Tommie Harris (Drums), die später in seiner ersten eigenen Band die Rhythmussektion bildeten. In Deutschland war der gelernte Kaufmann Tommy Schneller kurzzeitig bei der Frankfurter Konzertagentur Lynro Music als Booker, Veranstaltungsassistent und Tourmanager tätig. Zu seinen Klienten zählten etwa Sweets Edison, Red Holloway und Ed Thigpen; mit ihnen stand der Saxophonist auch teilweise auf der Bühne. Des Weiteren war er als Roadmanager für John Hendrix, Clark Terry und Ray Brown tätig. In Zusammenarbeit mit der Bluesnight Band sowie der Grand Jam Band arbeitete Tommy Schneller seit 2000 mit diversen Größen aus der Bluesszene zusammen – darunter Larry Garner, Andreas Schmidt-Martelle, Rolf Stahlhofen und Ron Williams[2].

Eigene Projekte

Zurück in Osnabrück gründete Tommy Schneller zusammen mit dem Bassisten Olli Geselbracht das Label „Out Of Space“ und nahm im Februar 1997 seine erste Solo CD „Blown Away“ auf. Es folgten weitere Veröffentlichungen als Tommy Schneller Band und Bluesin’ the Groove, einem Projekt, das er zusammen mit Christian Rannenberg und Alex Lex 2010 etablierte. Zudem ist er ein gefragter Studiomusiker. Tommy Schneller nahm unter anderem mit Gregor Hilden, Supercharge und Henrik Freischlader auf. Letzterer zeichnete auch als Produzent seines Albums „Smiling for a Reason“ (2011) verantwortlich, das mit dem Vierteljahrespreis der Deutschen Schallplattenkritik ausgezeichnet wurde.

Tommy Schneller Band

Zur Tommy Schneller Band gehören als feste Besetzung noch Jens Filser (Gitarre, Gesang), Gregory Barrett (Keyboard, Gesang), Gary Winters (Trompete, Flügelhorn, Gesang), Dieter Kuhlmann (Trombone, Saxophon), Bernhard Weichinger (Schlagzeug, Gesang) und Maik Reishaus (Bass, Gesang).[3]

Neben eigenen Stücken von Tommy Schneller spielt die Band Klassiker aus den Bereichen Blues, Funk und Soul.

Even as a child Tommy Schneller knew what he wanted to be when he grew up and didn't once change his mind--after catching the musical virus from an Elvis cassette, he set his sights on music and never looked back. Schneller grew up in Germany's "Blues Capital", Osnabrueck, well -known for the number of nationally active artists in the genre who live there, and while still young he began to appear regularly at the legendary Monday jams in the city's live music institution the "Pink Piano".

In 1987 he worked his first professional gigs with a number of acts, and ten years later

delivered his debut CD "BLOWING AWAY". Since then he has toured and performed

regularly throughout Europe's rich network of great music clubs and festivals. By 2004

Schneller had released two more albums, "BLUES FOR THE LADIES" (2000), the popular title

cut of which was rearranged and recorded again for the new CD, and "A HEARTBEAT AWAY"

(2004).

Beyond the recordings and shows under his own name Schneller has worked with a number

of other international artists as a member of the "Blues Night Band" since the turn of the

century including (among others):

the Ford Blues Band, Sydney Youngblood, Ron Williams, Rolf Stahlhofen, Red Holloway,

Angela Brown and MANY others. In addition, he recently released the trio CD "LET'S GET

HIGH" with "Bluesin' the Groove" in which he is joined by piano icon Christian Rannenberg

and young lion drummer/singer Alex Lex.

In 2007 Schneller met the guitarist, singer and multi-instrumentalist HENRIK FREISCHLADER,

with whom he worked beginning in 2008 in the formation "5 LIVE". With the support of

major German broadcaster NDR (North German Broadcasting) the CD "5 LIVE: IN THE KITCHEN" was released.

In 2010 Tommy received the offer from Freischlader which resulted in the current CD

"SMILING FOR A REASON" (2011): a mix of funky blues and soul which infects the listener

with its driving rhythms. With one exception (the Al Green classic "Never Found Me a Girl")

the recording is made up of compositions by Freischlader, keyboarder Barrett and Schneller

himself. Tommy Schneller has dedicated "SMILING FOR A REASON" to his late father Konrad

Schneller, for many years a judge and state representative for the CDU party in the Lower

Saxony Assembly:

"Things weren't always rosy between us. How could they be? As a conservative politician

and public figure my father had to deal with the escapades of a teenager who had just

discovered Elvis and was swept up by youthful rebellion. Not easy for him! But he let me

find my way...he supported me in the search for a calling that would bring me happiness,

and for that I will be eternally grateful."

In 1987 he worked his first professional gigs with a number of acts, and ten years later

delivered his debut CD "BLOWING AWAY". Since then he has toured and performed

regularly throughout Europe's rich network of great music clubs and festivals. By 2004

Schneller had released two more albums, "BLUES FOR THE LADIES" (2000), the popular title

cut of which was rearranged and recorded again for the new CD, and "A HEARTBEAT AWAY"

(2004).

Beyond the recordings and shows under his own name Schneller has worked with a number

of other international artists as a member of the "Blues Night Band" since the turn of the

century including (among others):

the Ford Blues Band, Sydney Youngblood, Ron Williams, Rolf Stahlhofen, Red Holloway,

Angela Brown and MANY others. In addition, he recently released the trio CD "LET'S GET

HIGH" with "Bluesin' the Groove" in which he is joined by piano icon Christian Rannenberg

and young lion drummer/singer Alex Lex.

In 2007 Schneller met the guitarist, singer and multi-instrumentalist HENRIK FREISCHLADER,

with whom he worked beginning in 2008 in the formation "5 LIVE". With the support of

major German broadcaster NDR (North German Broadcasting) the CD "5 LIVE: IN THE KITCHEN" was released.

In 2010 Tommy received the offer from Freischlader which resulted in the current CD

"SMILING FOR A REASON" (2011): a mix of funky blues and soul which infects the listener

with its driving rhythms. With one exception (the Al Green classic "Never Found Me a Girl")

the recording is made up of compositions by Freischlader, keyboarder Barrett and Schneller

himself. Tommy Schneller has dedicated "SMILING FOR A REASON" to his late father Konrad

Schneller, for many years a judge and state representative for the CDU party in the Lower

Saxony Assembly:

"Things weren't always rosy between us. How could they be? As a conservative politician

and public figure my father had to deal with the escapades of a teenager who had just

discovered Elvis and was swept up by youthful rebellion. Not easy for him! But he let me

find my way...he supported me in the search for a calling that would bring me happiness,

and for that I will be eternally grateful."

Tommy Schneller & Band - Too through with you / Lindenbrauerei Unna Germany 2014

Fernsehkonzert: "Tommy Schneller Band" aus Osnabrück

Live-Musik - präsentiert von Kanal 21, Bielefeldhttps://www.nrwision.de/programm/sendungen/ansehen/fernsehkonzert-tommy-schneller-band-aus-osnabrueck-2.html

Paul Olsen *18.09.

https://www.facebook.com/Scrapomatic/photos

Scrapomatic is an American blues duo, consisting of two performers, Paul Olsen, and Mike Mattison. Backed by other musicians, they have performed together since the mid-1990s, and the duo often open for The Derek Trucks Band, of which Mattison is also a member, performing as their lead vocalist since 2003.[1]

Biography

The duo Scrapomatic was founded in Minneapolis-Saint Paul, Minnesota, by Paul Olsen and Mike Mattison, who were raised and schooled there. Both musicians were taught separately but came to embrace an Americana-flavored roots-based approach to music. Both had formal musical training and found common ground in jazz and funk rhythms. They gained recognition when the duo were nominated for Best R&B Group and Best Male Vocalist by the Minnesota Music Awards.[2] After a move to Brooklyn, they have performed throughout New York City, and played Carnegie Hall.

Olsen is now primarily active as an ASCAP award-winning songwriter, producer and musical director. Mattison is involved in several projects that have sprung from his association with Derek Trucks, including his bands.

Career

2003 was the year that the two men released their first self-titled album, Scrapomatic, receiving very good reviews. Scrapomatic often are the opening act for The Derek Trucks Band and Susan Tedeschi.

Biography

The duo Scrapomatic was founded in Minneapolis-Saint Paul, Minnesota, by Paul Olsen and Mike Mattison, who were raised and schooled there. Both musicians were taught separately but came to embrace an Americana-flavored roots-based approach to music. Both had formal musical training and found common ground in jazz and funk rhythms. They gained recognition when the duo were nominated for Best R&B Group and Best Male Vocalist by the Minnesota Music Awards.[2] After a move to Brooklyn, they have performed throughout New York City, and played Carnegie Hall.

Olsen is now primarily active as an ASCAP award-winning songwriter, producer and musical director. Mattison is involved in several projects that have sprung from his association with Derek Trucks, including his bands.

Career

2003 was the year that the two men released their first self-titled album, Scrapomatic, receiving very good reviews. Scrapomatic often are the opening act for The Derek Trucks Band and Susan Tedeschi.

Scrapomatic - Louisiana Anna

Scrapomatic featuring Mike Mattison: Full Concert

R.I.P.

Blind Willie Johnson +18.09.1945

„Blind” Willie Johnson (* 22. Januar 1897; † 18. September 1945) war ein US-amerikanischer Sänger und Gitarrist, dessen Werk sowohl im Blues als auch im Spiritual wurzelte. Während seine Texte ausnahmslos religiösen Inhalts waren, leiteten sich seine musikalischen Ausdrucksformen aus beiden traditionellen Quellen ab.

Nach einer später entdeckten Sterbeurkunde wurde Johnson 1897 in der Nähe von Brenham in Texas geboren. Vorher waren andere Geburtsorte (Waco, Temple) und auch ein späteres Geburtsdatum (um 1902) genannt worden. Seine Kindheit verbrachte er größtenteils in Marlin. Johnsons Mutter starb, als er noch ein kleines Kind war; sein Vater heiratete danach erneut. Er war nicht von Geburt an blind. Als er ungefähr sieben Jahre alt war, schüttete ihm seine Stiefmutter infolge eines Wutanfalls Lauge in die Augen. Als Johnson älter wurde, begann er auf der Straße Gitarre zu spielen, um sich Geld zu verdienen. Schon damals verwendete er die Slide-Technik, jedoch nicht mit einem abgebrochenen Flaschenhals, sondern mit einer Zange. Johnson hatte aber eigentlich nicht vor, Blues-Musiker zu sein, der bibelfeste junge Mann wollte lieber Gospel singen.

Karriere

1927 lernte er seine erste Frau Willie B. Harris kennen, zusammen mit ihr begann er um Dallas und Waco herum aufzutreten. Sie inspirierte ihn, alte Lieder des 19. Jahrhunderts mit in sein Repertoire aufzunehmen, unter anderem Keep Your Lamp Trimmed and Burning und Praise God I’m Satisfied. Später war Johnson mit einer Frau namens Angeline verheiratet. Bis heute ist keine Heiratsurkunden oder dergleichen gefunden worden, die belegen, ob bzw. in welchen Zeiträumen Johnson verheiratet war. Es wird angenommen, dass er mit Willie B. Harris von 1926 (oder 1927) bis 1932 (oder 1933) verheiratet war. Seine zweite Frau überlebte ihn und arbeitete als Krankenschwester.

Am 3. Dezember 1927 nahm er in den Studios der Columbia Records seine ersten sechs Stücke auf, darunter sein wohl bekanntestes Dark Was The Night – Cold Was The Ground. Ein Jahr später hielt er mit seiner Frau erneut eine Aufnahme-Session ab; 1929 reisten die beiden mit Elder Dave Ross nach New Orleans, wo er für Columbia zehn Songs aufnahm, darunter das Gospel-Stück Let Your Light Shine On Me. Außerdem spielte er nur noch einmal Lieder ein, im April 1930. Wieder dabei war seine Frau Willie. Dies war das letzte Mal für Johnson, dass er Platten aufnahm. Fortan trat er auf der Straße auf, um sich seinen Lebensunterhalt zu verdienen.

1945, vielleicht auch erst 1947, brannte sein Haus nieder. Da Johnson jedoch sehr arm war, blieb im nichts anderes übrig, als weiterhin in der Ruine zu leben. Blind Willie Johnson verstarb danach an einer Lungenentzündung.

Johnsons Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground ist auf der goldenen Schallplatte Voyager Golden Record enthalten, die sich an Bord der beiden interstellaren Raumsonden Voyager 1 und Voyager 2 befindet. Ebenso in der legendären Wireliste The Wire's "100 Records That Set The World On Fire (While No One Was Listening)".

"Blind" Willie Johnson (January 22, 1897 – September 18, 1945) was a gospel blues singer and guitarist. While the lyrics of his songs were usually religious, his music drew from both sacred and blues traditions. It is characterized by his slide guitar accompaniment and tenor voice, and his frequent use of a lower-register 'growl' or false bass voice.[1]

Life

According to his death certificate, Johnson was born in 1897, in Independence, near Brenham, Texas. (Earlier, Temple, Texas had been suggested as his birthplace.)[2] When he was five, he told his father he wanted to be a preacher and then made a cigar box guitar for himself. His mother died when he was young, and his father remarried soon after her death.[3]

Johnson was not born blind. Although it is not certain how he lost his sight, his alleged widow Angeline Johnson told Samuel Charters that when Willie was seven his father beat his stepmother after catching her going out with another man; and that she in spite blinded young Willie by throwing lye in his face.[3]

It is believed that Johnson married at least twice. He was married to Willie B. Harris. Her recollection of their initial meeting was recounted in the liner notes for Yazoo Records's album Praise God I'm Satisfied. He was later alleged to have been married to a woman named Angeline. Johnson was also said to be married to a sister of blues artist L. C. Robinson.[citation needed] No marriage certificates have yet been discovered. As Angeline Johnson often sang and performed with him,[citation needed] the first person to attempt to research his biography, Samuel Charters, made the mistake of assuming it was Angeline who had sung on several of Johnson's records.[2] However, later research showed that it was Willie B. Harris.[2]

Johnson remained poor until the end of his life, preaching and singing in the streets of several Texas cities including Beaumont. A city directory shows that in 1945, a Rev. W. J. Johnson, undoubtedly Blind Willie, operated the House of Prayer at 1440 Forrest Street, Beaumont, Texas.[2] This is the same address listed on Johnson's death certificate. In 1945, his home burned to the ground. With nowhere else to go, Johnson lived in the burned ruins of his home, sleeping on a wet bed in the August/September Texas heat. He lived like this until he contracted malarial fever, and died on September 18, 1945. (The death certificate reports the cause of death as malarial fever, with syphilis and blindness as contributing factors.)[2] In an interview, Angeline said that she tried to take him to a hospital, which refused to admit him because he was blind. Other sources report that the refusal was due to his being black.

According to his death certificate, he was buried in Blanchette Cemetery, Beaumont. The location of that cemetery had been forgotten until it was rediscovered in 2009. His exact gravesite remains unknown; but in 2010, the researchers who had identified the cemetery erected a monument there in his honor.[4]

Musical career

His father would often leave him on street corners to sing for money. Tradition has it that he was arrested for nearly starting a riot at a New Orleans courthouse with a powerful rendition of "If I Had My Way I'd Tear the Building Down", a song about Samson and Delilah. According to Samuel Charters, however, he was simply arrested while singing for tips in front of the Customs House by a police officer who misconstrued the title lyric and mistook it for incitement.[3] Timothy Beal argued that the officer did not, in fact, misconstrue the meaning of the song, but that "the ancient story suddenly sounded dangerously contemporary" to him.[5]

Johnson made 30 commercial recording studio record sides (29 songs) in five separate sessions for Columbia Records from 1927–1930.[6] On some of these recordings Johnson uses a fast rhythmic picking style, while on others he plays slide guitar. According to a reputed one-time acquaintance, Blind Willie McTell (1898–1959), Johnson played with a brass ring; but the bluesman Tom Shaw, interviewed by Guido van Rijn in 1972, says that he used a knife.[7] However, in enlargement, the only known photograph of Johnson seems to show that there is an actual bottleneck on the little finger of his left hand.[8] While his other fingers are apparently fretting the strings, his little finger is extended straight—which also suggests there is a slide on it as well.

Legacy

Several of Blind Willie Johnson's songs have been interpreted by other musicians, including "Jesus Make Up My Dying Bed", "It's Nobody's Fault but Mine", "Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground", "John the Revelator", "You'll Need Somebody on Your Bond", "Motherless Children" and "Soul of a Man".

"Dark Was the Night" is one of the music tracks on the Voyager Golden Record, copies of which were placed in 1977 on both the unmanned Voyager Project space probes. It is the penultimate track, preceding only the Cavatina from Beethoven's String Quartet Op. 130: the blind musician and the deaf one side by side. The astronomer Timothy Ferris, who worked with Carl Sagan in selecting those tracks, has said:[9][10]

"Johnson's song concerns a situation he faced many times, nightfall with no place to sleep. Since humans appeared on Earth, the shroud of night has yet to fall without touching a man or woman in the same plight."

Ry Cooder's slide guitar title song and soundtrack music of the Wim Wenders film Paris, Texas (1984) was based on "Dark Was the Night".

"Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground" was played in the TV series The West Wing (season 5) episode 13, The Warfare of Genghis Khan. "It's Nobody's Fault but Mine" was played in the TV series The Walking Dead (season 5) episode 4 Slabtown.

Life

According to his death certificate, Johnson was born in 1897, in Independence, near Brenham, Texas. (Earlier, Temple, Texas had been suggested as his birthplace.)[2] When he was five, he told his father he wanted to be a preacher and then made a cigar box guitar for himself. His mother died when he was young, and his father remarried soon after her death.[3]

Johnson was not born blind. Although it is not certain how he lost his sight, his alleged widow Angeline Johnson told Samuel Charters that when Willie was seven his father beat his stepmother after catching her going out with another man; and that she in spite blinded young Willie by throwing lye in his face.[3]

It is believed that Johnson married at least twice. He was married to Willie B. Harris. Her recollection of their initial meeting was recounted in the liner notes for Yazoo Records's album Praise God I'm Satisfied. He was later alleged to have been married to a woman named Angeline. Johnson was also said to be married to a sister of blues artist L. C. Robinson.[citation needed] No marriage certificates have yet been discovered. As Angeline Johnson often sang and performed with him,[citation needed] the first person to attempt to research his biography, Samuel Charters, made the mistake of assuming it was Angeline who had sung on several of Johnson's records.[2] However, later research showed that it was Willie B. Harris.[2]

Johnson remained poor until the end of his life, preaching and singing in the streets of several Texas cities including Beaumont. A city directory shows that in 1945, a Rev. W. J. Johnson, undoubtedly Blind Willie, operated the House of Prayer at 1440 Forrest Street, Beaumont, Texas.[2] This is the same address listed on Johnson's death certificate. In 1945, his home burned to the ground. With nowhere else to go, Johnson lived in the burned ruins of his home, sleeping on a wet bed in the August/September Texas heat. He lived like this until he contracted malarial fever, and died on September 18, 1945. (The death certificate reports the cause of death as malarial fever, with syphilis and blindness as contributing factors.)[2] In an interview, Angeline said that she tried to take him to a hospital, which refused to admit him because he was blind. Other sources report that the refusal was due to his being black.

According to his death certificate, he was buried in Blanchette Cemetery, Beaumont. The location of that cemetery had been forgotten until it was rediscovered in 2009. His exact gravesite remains unknown; but in 2010, the researchers who had identified the cemetery erected a monument there in his honor.[4]

Musical career

His father would often leave him on street corners to sing for money. Tradition has it that he was arrested for nearly starting a riot at a New Orleans courthouse with a powerful rendition of "If I Had My Way I'd Tear the Building Down", a song about Samson and Delilah. According to Samuel Charters, however, he was simply arrested while singing for tips in front of the Customs House by a police officer who misconstrued the title lyric and mistook it for incitement.[3] Timothy Beal argued that the officer did not, in fact, misconstrue the meaning of the song, but that "the ancient story suddenly sounded dangerously contemporary" to him.[5]

Johnson made 30 commercial recording studio record sides (29 songs) in five separate sessions for Columbia Records from 1927–1930.[6] On some of these recordings Johnson uses a fast rhythmic picking style, while on others he plays slide guitar. According to a reputed one-time acquaintance, Blind Willie McTell (1898–1959), Johnson played with a brass ring; but the bluesman Tom Shaw, interviewed by Guido van Rijn in 1972, says that he used a knife.[7] However, in enlargement, the only known photograph of Johnson seems to show that there is an actual bottleneck on the little finger of his left hand.[8] While his other fingers are apparently fretting the strings, his little finger is extended straight—which also suggests there is a slide on it as well.

Legacy

Several of Blind Willie Johnson's songs have been interpreted by other musicians, including "Jesus Make Up My Dying Bed", "It's Nobody's Fault but Mine", "Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground", "John the Revelator", "You'll Need Somebody on Your Bond", "Motherless Children" and "Soul of a Man".

"Dark Was the Night" is one of the music tracks on the Voyager Golden Record, copies of which were placed in 1977 on both the unmanned Voyager Project space probes. It is the penultimate track, preceding only the Cavatina from Beethoven's String Quartet Op. 130: the blind musician and the deaf one side by side. The astronomer Timothy Ferris, who worked with Carl Sagan in selecting those tracks, has said:[9][10]

"Johnson's song concerns a situation he faced many times, nightfall with no place to sleep. Since humans appeared on Earth, the shroud of night has yet to fall without touching a man or woman in the same plight."

Ry Cooder's slide guitar title song and soundtrack music of the Wim Wenders film Paris, Texas (1984) was based on "Dark Was the Night".

"Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground" was played in the TV series The West Wing (season 5) episode 13, The Warfare of Genghis Khan. "It's Nobody's Fault but Mine" was played in the TV series The Walking Dead (season 5) episode 4 Slabtown.

Blind Willie Johnson - Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground

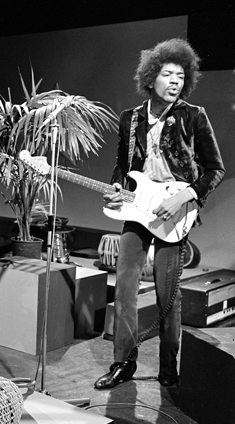

Jimi Hendrix +18.09.1970

James Marshall „Jimi“ Hendrix (* 27. November 1942 in Seattle, Washington; † 18. September 1970 in London) war ein US-amerikanischer Gitarrist, Komponist und Sänger.

Jimi Hendrix, der wegen seiner experimentellen und innovativen Spielweise auf der E-Gitarre als einer der bedeutendsten Gitarristen gilt, hatte nachhaltigen Einfluss auf die Entwicklung der Rockmusik, obwohl er nur dreieinhalb Jahre nach seinem Bekanntwerden starb. Mit seinen Bands, unter anderem The Jimi Hendrix Experience und Gypsy Sun & Rainbows, trat er auf dem Monterey Pop Festival, dem Woodstock-Festival und dem Isle of Wight Festival 1970 auf.

Biografie

Kindheit und Jugend

Jimi Hendrix war der Sohn von James Allen Hendrix und Lucille Jeter und hieß zunächst John Allen Hendrix. Sein Vater war Afroamerikaner und seine Mutter cherokee-irischer Abstammung.[1] James Allen Hendrix war zur Zeit der Geburt seines Sohnes gerade mit der US-Armee in Alabama stationiert. Nach seiner Entlassung im Jahr 1946 ließ er den Namen seines Sohnes in James Marshall Hendrix ändern.[2] Die Eltern, die 1948 noch einen weiteren gemeinsamen Sohn namens Leon bekamen, ließen sich 1950 scheiden. Jimi Hendrix wuchs fortan bei seinem Vater auf.

Sein erstes Musikinstrument war eine Mundharmonika, die er mit vier Jahren erhielt.[3] Als Jugendlicher begann er sich für Rock ’n’ Roll zu begeistern. Er besuchte unter anderem Konzerte von Elvis Presley und Little Richard. Mit 13 Jahren bekam er von seinem Vater eine einsaitige Ukulele geschenkt, die dieser beim Aufräumen in einer Garage gefunden hatte.[4] Im Sommer 1957 erwarb sein Vater für fünf Dollar eine gebrauchte akustische Gitarre, auf der Hendrix mit seiner ersten Band The Velvetones nur eine kurze Zeit spielte, denn schon bald bekam er eine elektrische Gitarre, die „Supro Ozark 1560S“ geschenkt. Diese spielte er auch in seiner zweiten Band The Rocking Kings.

Nach dem erfolgreichen Abschluss der Highschool besuchte Hendrix die Garfield High School, die er jedoch 1959 wegen schlechter Noten verlassen musste. Nach einem Autodiebstahl stellte man ihn vor die Wahl, zwei Jahre im Gefängnis zu verbringen oder der Army beizutreten. Im Mai 1961 verpflichtete sich Jimi Hendrix für drei Jahre und kam nach der Grundausbildung zur 101. US-Luftlandedivision in Fort Campbell. Hendrix fiel bei der US Army sehr schnell unangenehm auf. Vorgesetzte bemängelten seine geringe Motivation und Verstöße gegen Befehle und Regeln. Hendrix könne sich nicht auf seine Pflichten konzentrieren, da er außerhalb des Dienstes zu viel Gitarre spiele und ständig daran denke. Außerdem besitze er keine guten Charaktereigenschaften. Nach 13 Monaten wurde Hendrix vorzeitig entlassen.[5]

Karrierebeginn als Musiker

Während seines Militärdienstes hatte er Billy Cox kennen gelernt, der Bass in den Wohltätigkeitsclubs in Nashville spielte. Mit Cox zusammen gründete Hendrix die Band The King Kasuals. Zusätzlich spielte er in den folgenden Jahren als Begleitmusiker unter anderem für Little Richard, The Supremes, The Isley Brothers und Jackie Wilson.

Im Januar 1964 zog er in den New Yorker Stadtteil Harlem. Bereits im Monat darauf konnte er einen Wettbewerb des Apollo Theater gewinnen.

1965 übernahm Hendrix die Rolle des Gitarristen bei den Isley Brothers und begleitete sie auf einer Tour durch die USA. Noch im gleichen Jahr stieg Hendrix bei der New Yorker Band Curtis Knight and the Squires ein. Curtis Knights Manager, Ed Chalpin, bot an, ihn unter Vertrag zu nehmen. Hendrix unterschrieb und bekam einen Vorschuss von einem Dollar und einen Anteil von einem Prozent an den Lizenzeinnahmen und verpflichtete sich gleichzeitig, drei Jahre lang exklusiv für ihn zu spielen.[6] Doch auch sein Engagement in dieser Gruppe hatte nur kurzen Bestand.

Die erste Band, in der Hendrix selbst als Frontmann und Sänger aktiv war, war die 1965 gegründete Formation Jimmy James and the Blue Flames. In der zweiten Hälfte des Jahres 1965 und Anfang 1966 spielte Hendrix mit diesen Musikern in Clubs des Greenwich Village.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience

Als Hendrix gemeinsam mit seinen Begleitmusikern am 3. August 1966 im „Cafe Wha?“ in New Yorks Künstlerviertel Greenwich Village auftrat, war auch der ehemalige Animals-Bassist Chas Chandler anwesend, der von Hendrix’ künstlerischer Leistung beeindruckt war. Er bot ihm einen Vertrag an, dem zufolge Hendrix in London eine neue Band aufbauen sollte. Für die neue Funktion wurde das alte Pseudonym Jimmy James aufgegeben. Hendrix sollte künftig unter eigenem Namen auftreten. Gemeinsam mit Schlagzeuger Mitch Mitchell (vorher Georgie Fame’s Blue Flames) und Bassist Noel Redding wurde so die Jimi Hendrix Experience September 1966 in London gegründet. Chandler fungierte auch in Zukunft als Manager und Produzent für die Gruppe. Er war für den künstlerischen Teil des Managements zuständig, während sich Michael Jeffery um das Finanzielle kümmerte. Jeffery war bereits Chandlers Manager gewesen, als dieser bei den Animals spielte.

Ihr erster gemeinsamer Auftritt war als Vorgruppe für Johnny Hallyday im Pariser Olympia. Die ersten Songs, Hey Joe und Stone Free, wurden im Oktober/November 1966 aufgenommen. Die Single wurde noch im Dezember 1966 veröffentlicht und platzierte sich im Februar 1967 in England auf Platz 4 der Hitparade. Das erste Album, Are You Experienced, erreichte Platz 2 der UK-Charts.

Am 18. Juni 1967 trat Hendrix mit seiner Band auf dem Monterey Pop Festival auf, wodurch seine Popularität sehr gesteigert wurde. Bekannt wurde der Auftritt auch dadurch, dass Hendrix am Ende nach dem neunten Song Wild Thing seine Gitarre anzündete. Er selbst äußerte sich dazu so:

“The time I burned my guitar it was like a sacrifice. You sacrifice the things you love. I love my guitar.”

„Als ich meine Gitarre verbrannte, war das wie ein Opfer. Man opfert die Dinge, die man liebt. Ich liebe meine Gitarre.“

– Jimi Hendrix[7]

Nach der Veröffentlichung von Axis: Bold as Love startete die Band im Februar 1968 eine längere Tour durch die USA, auf der sie unter anderem auch im Fillmore West in San Francisco auftrat. Noch im selben Jahr veröffentlichte sie Electric Ladyland mit den bekannten Songs Voodoo Child (Slight Return) und All Along the Watchtower. Das Album eroberte Platz 1 der Billboard-Charts. Der letzte gemeinsame Auftritt der Jimi Hendrix Experience fand am 29. Juni 1969 in Denver statt.

Ebenfalls im Februar 1968 erstellte das damalige Groupie Cynthia Plaster Caster einen Abguss von Hendrix' Penis. Eine Kopie davon findet sich heute im Rock’n’popmuseum in Gronau (Westf.).[8]

Auftritt in Woodstock

Das Jahr 1969 begann mit Problemen mit der kanadischen Justiz. Im Mai wurden bei einer Kontrolle am Flughafen von Toronto in Hendrix' Gepäck Heroin und Haschisch gefunden. Hendrix behauptete, die Drogen seien ohne sein Wissen hineingelangt.

Im Sommer 1969 stellte er für das Woodstock-Festival eine neue Band zusammen. Diese nannte er Gypsy Sun & Rainbows – zugehörig waren Mitch Mitchell am Schlagzeug, sein alter Armee-Freund Billy Cox am Bass, Larry Lee an der Rhythmusgitarre und zwei Perkussionisten. Witterungsbedingt verzögerte sich der Auftritt der Band und so traten die Musiker erst am frühen Montagmorgen des 18. August 1969 auf, als das Festival eigentlich schon vorbei sein sollte.

Von den mehr als 400.000 Besuchern waren zu diesem Zeitpunkt gerade noch rund 25.000 anwesend.[9]

Bei diesem Auftritt präsentierte Hendrix zum ersten Mal seine in konservativen Kreisen umstrittene und nachfolgend weltbekannte Interpretation der US-amerikanischen Nationalhymne The Star-Spangled Banner. Durch seine Spieltechnik und den Einsatz von Effekten (vor allem Wah-Wah und Fuzz-Face) verfremdete er die Hymne und nahm somit auf akustische Weise Stellung zum Kriegsgeschehen in Vietnam.

„Durch Spieltechnik und den Einsatz von Effekten ließ er zwischen den bekannten Motiven der Hymne auch Kriegsszenen hörbar werden, darunter verblüffend deutlich Maschinengewehrsalven, Fliegerangriffe und Geschosseinschläge.“[10]

Band of Gypsys

Nach dem Woodstock-Auftritt gab die Band nur noch zwei Konzerte und löste sich dann auf. Um Ed Chalpins Ansprüche aus dem 1-Dollar-Vertrag zu befriedigen, wurde ein Konzert mitgeschnitten, das Silvester 1969 im Fillmore East stattfand. Dafür stellte Hendrix eine neue Band namens Band of Gypsys mit Billy Cox am Bass und Buddy Miles am Schlagzeug zusammen.

Die neue Jimi Hendrix Experience

Die Band of Gypsys war gerade mal einen Monat zusammen aufgetreten, als Hendrix im März 1970 die Jimi Hendrix Experience neu formierte. Er übernahm Billy Cox aus der Band of Gypsys und spielte weiter mit Mitch Mitchell.

1970 fanden zahlreiche, oft spontane Studioaufnahmen mit wechselnden Besetzungen statt, die in ein geplantes Album mit dem Arbeitstitel First Rays of the New Rising Sun münden sollten. Eine Auswahl der Songs wurde 1971 als Cry Of Love veröffentlicht, als komplettes Album erschien es erst 1997. Für die Aufnahmen ließ Hendrix in der 8th Street in New York ein eigenes Aufnahmestudio errichten, das im August 1970 fertiggestellt wurde. Als Name wurde „Electric Lady Studios“ gewählt.

In diesem Jahr ging die Band auf ihre letzte US- und Europa-Tournee. Auftakt in Europa war das Isle of Wight Festival am 30. August 1970. Nach anschließenden Auftritten in Stockholm, Kopenhagen und Berlin (am 4. September 1970 in der Deutschlandhalle) absolvierte Hendrix beim Love-and-Peace-Festival am 6. September 1970 auf der schleswig-holsteinischen Ostseeinsel Fehmarn seinen letzten Auftritt. Später wurde dort ein Gedenkstein platziert. Noch heute werden regelmäßige Revival-Festivals durchgeführt.[11]

Im selben Jahr wirkte Hendrix bei den Aufnahmen für das Solo-Debütalalbum von Stephen Stills mit. Dessen Erscheinen im November 1970 erlebte er nicht mehr. Stills widmete das Album „James Marshall Hendrix“.

Tod

Während der vorangegangenen Jahre hatte sich Hendrix’ Drogenkonsum massiv verstärkt. Als Konsequenz hatte insbesondere sein Auftreten auf den letzten Konzerten sehr gelitten.

„Er verlor an Bodenhaftung, lieferte unter dem Einfluss von Drogen teilweise katastrophale Konzerte ab und verfiel im Anschluss daran immer häufiger in Depressionen. […] das Konzert auf der Ostseeinsel Fehmarn geriet zum Desaster. Jimi Hendrix kehrte ausgelaugt und nervlich zerrüttet nach London zurück.“[12]

Am 17. September 1970 jammte Hendrix zusammen mit Eric Burdon und War in Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club in London. Diese Jamsession wurde von Fans auf Tonband aufgenommen und ist ein unter Insidern begehrter Mitschnitt, da es die letzte Aufnahme von Hendrix ist. Am frühen Morgen des nächsten Tages, am 18. September 1970, wurde Hendrix tot im Londoner Samarkand Hotel aufgefunden, nachdem er die Nacht dort mit seiner Freundin Monika Dannemann verbracht hatte. Während als Todesursache zunächst härtere Drogen vermutet worden waren, wurde später festgestellt, dass Hendrix Alkohol und Schlaftabletten konsumiert hatte und an seinem Erbrochenen erstickt war.[13] In seiner Lunge fand man große Mengen Rotwein. Laut dem zuständigen Krankenhausarzt habe Hendrix ein mit Rotwein getränktes Stück Stoff um den Hals getragen, einen Pullover oder ein Handtuch.[14]

Obwohl die Todesursache offiziell geklärt war („Tod durch Ersticken“), entstanden um Hendrix’ Tod zahlreiche Spekulationen. Auch wenn sein Manager Chas Chandler mit den Worten zitiert wird, dass Hendrix’ Tod absehbar gewesen sei,[15] entstanden Verschwörungstheorien, dass es sich um Mord oder Selbstmord gehandelt habe. 1993 wurden erneut Ermittlungen aufgenommen, da eine andere ehemalige Freundin von Hendrix klagte, dass Dannemann den Notarzt zu spät alarmiert habe. Ein Urteil gegen Dannemann wurde in dem Prozess nicht gesprochen.[16]

In seiner 2009 veröffentlichten Autobiografie Rock Roadie beschuldigt Hendrix’ ehemaliger Roadie James Wright den Hendrix-Manager Michael Jeffery des Mordes an Hendrix: Jeffery habe eine Lebensversicherung für Hendrix abgeschlossen und sich selbst als Begünstigten eingetragen, um sich eine Versicherungssumme in Höhe von 1,2 Millionen Pfund auszahlen zu lassen.[17]

Jimi Hendrix wurde in Seattle neben den Gräbern seiner Mutter und Großmutter bestattet. Nach seinem Tod wurde bekannt, dass er ein Projekt mit der Supergroup Emerson, Lake and Palmer geplant hatte.[18]

Hendrix starb im Alter von 27 Jahren und wird dadurch, wie andere einflussreiche Musiker, dem Klub 27 zugerechnet. Ebenso wie Janis Joplin und Jim Morrison wird ihm zugeschrieben, nach der Devise „Live Fast, Love Hard, Die Young“ gelebt zu haben.

Politische Aussagen

Obwohl Jimi Hendrix kein politischer Aktivist war, hatte er in den US-amerikanischen Medien einige Kommentare zu den Black Panthers abgegeben, die eine Art „geistige Verbundenheit“ zum Ausdruck bringen sollten, wie er es nannte. In dem 2004 veröffentlichten Dokumentarfilm Jimi Hendrix – The Last 24 Hours von Michael Parkinson wird berichtet, dass Hendrix am 28. Januar 1970 beim Benefizkonzert des Vietnam Moratorium Committee „Winter Festival Of Peace“ im Madison Square Garden teilnahm und Geld an die Black Panthers spendete. Auch ein Konzert für Bobby Seale und die Chicago Seven wird erwähnt. Dadurch kam Hendrix auf den Sicherheitsindex des FBI, wie aus dem freigegebenen Teil der FBI-Akten nachweisbar ist.

Auszeichnungen und Ehrungen

Im Jahr 1992 wurde Hendrix posthum der Grammy für sein Lebenswerk verliehen, und er wurde in die Rock and Roll Hall of Fame aufgenommen.[19] Zwei Jahre darauf wurde ihm ein Stern auf dem Hollywood Walk of Fame gewidmet.

Erst 1995 erhielten sein Vater und seine Schwester die Kontrolle über Hendrix’ Erbe zurück. In dieser Zeit wurde der Wert dieses Vermächtnisses auf vierzig bis einhundert Millionen US-Dollar geschätzt.[20] 1998 wurde Hendrix in die NAMA Hall of Fame der Native Americans aufgenommen.[21] 2000 gründete Paul Allen, Mitbegründer von Microsoft, das 240 Millionen Dollar teure Experience Music Project in Seattle, in dem eine große Zahl von Hendrix-Memorabilia ständig ausgestellt wird, unter anderem Gitarren, Kleidung und Songtexte.[22] 2006 benannte Hendrix’ Heimatstadt Seattle einen Park nach ihm, obwohl sie sich zu Lebzeiten eher distanziert zu ihm verhalten hatte.[23]

Daneben wurde er von vielen Musikmagazinen als herausragender Musiker anerkannt. Von Rolling Stone, Guitar World und anderen Zeitschriften wurde er zum besten E-Gitarristen aller Zeiten ernannt.[24] VH1 listete ihn an dritter Stelle der Best Hard Rock Artists of all time hinter Black Sabbath und Led Zeppelin und an gleicher Position bei den 100 Best Pop Artists of all time, nach den Rolling Stones und den Beatles, auf.

Musik

Hendrix’ Gitarrenspiel

Als Teenager hatte Hendrix hauptsächlich Blues- und Rock-’n’-Roll-Musiker wie Buddy Guy, Muddy Waters, B. B. King, Chuck Berry und Eddie Cochran als Vorbilder[25] und coverte auch deren Songs.[26] In seinen aktiven Jahren als Gitarrist imitierte er nicht nur deren Musik, sondern entwickelte den Musikstil weiter. Er prägte und veränderte insbesondere den Sound der Rock-Gitarre wesentlich. In seinen improvisierten Soli verwendete er Fuzz-Effektgeräte, ähnlich wie die Rolling Stones vor ihm, um den Klang zu verzerren, und nutzte früh ein Wah-Wah-Pedal. Im Gegensatz zu vielen frühen Rockgitarristen, die meist nur einfachere Akkorde oder nur Powerchords verwendeten, benutzte er bei der Begleitung auch komplexere Akkorde und für die Rockmusik ungewöhnliche Akkordfolgen, wie sie bis dahin eher im Bereich des Jazz eingesetzt wurden. Beispiele hierfür sind die Songs „Bold as love“ oder „May this be love“. Mittels des exzessiven Einsatzes des Tremolohebels auf seiner Fender Stratocaster, kombiniert mit einer völligen Übersteuerung der Verstärker, kreierte Hendrix völlig neue, psychedelische, sphärisch-klingende Sounds und Spielweisen auf der E-Gitarre – passend zu vielfach surrealen Texten. Das wohl bekannteste Beispiel für diese ungewöhnliche Expressivität auf der E-Gitarre ist seine Interpretation der amerikanischen Nationalhymne auf dem Woodstock-Festival. Einen weiteren Klangeffekt produzierte er einfach dadurch, dass er seine Gitarre um einen halben Ton tiefer stimmte, so dass insbesondere die von ihm heftig zur Unterstützung des Akkordspiels und der Licks eingesetzten tiefen Basstöne eine mächtigere Farbe bekamen. Eine Besonderheit seiner Spielweise bestand auch darin, dass er mittels des Daumens der Griffhand die Akkorde vervollständigte oder auch als Einzeltöne die Akkorde umspielte.

Gegen Ende der 1960er begannen zahlreiche Rockmusiker, besonders die aus dem Umfeld des Progressive Rock, mit längeren Improvisationen zu arbeiten, die bis dahin nur im Jazz üblich waren. Neben Eric Clapton war Hendrix einer der ersten Gitarristen, die dem Solospiel eine wesentliche Rolle zuwiesen. Hendrix konnte hier seine Fingerfertigkeit und Technik unter Beweis stellen. Indem er die Sologitarre derart in den Vordergrund brachte, veränderte sich in den Folgejahren der Status der Gitarristen in den Bands; sie wurden von bloßen Begleitmusikern zu eigenen Stars neben dem Sänger. In diesem Sinne war er Vorbild für das Hervortreten bekannter Gitarristen in den 1970ern, wie Jeff Beck, Ritchie Blackmore, Jimmy Page, Ted Nugent oder Tony Iommi.

Zu den von ihm beeinflussten Künstlern werden heute außerdem Stevie Ray Vaughan, Brian May, Prince, Eddie Van Halen, Kirk Hammett, John Frusciante und Uli Jon Roth gezählt.[27] Dutzende Bands coverten später Songs von Hendrix, insbesondere namhafte Gitarristen wie Eric Clapton, David Gilmour, Joe Satriani, Lenny Kravitz, Michael Schenker, Steve Vai, Slash und Yngwie Malmsteen, aber auch die Bands Pearl Jam, The Cure oder die Red Hot Chili Peppers. Von den vielen Roadies, die Hendrix auf seinen Touren begleiteten, erlangten einige später selber Berühmtheit. Beispielsweise waren Lemmy Kilmister (gründete später Motörhead),[28] Ace Frehley (später bei Kiss)[29] und Schauspieler und Komiker Phil Hartman[30] vor ihrer Karriere im Umfeld von Jimi Hendrix aktiv.

Hendrix’ Rhythmusarbeit zu Little Wing ist geprägt von Akkordgrundtönen, die er mit dem Daumen griff, erweitert mit tonartgerechten Verzierungen

Wenn Hendrix auf der Gitarre seinen Gesang begleitete, spielte er in aller Regel nicht nur die zugehörigen Akkorde, sondern untermalte diese durch eine Reihe von Verzierungen. Da er auf diese Weise gleichzeitig die Aufgabe des klassischen Rhythmusgitarristen und des Leadgitarristen übernahm, entsteht der Eindruck, als würden mehrere Gitarren gleichzeitig spielen. In einer Vielzahl von Licks und Fills, die Hendrix in seine Begleitung einbaute, zeigt sich seine künstlerische Kreativität.

Eine Eigenart von ihm war es, dass er Melodien und Akkorde nicht in Form von Noten oder Tabulatur niederschrieb, sondern Farben verwendete. Als Grund dafür gilt, dass Hendrix Synästhetiker war, also Töne und Farben zusammen wahrnehmen konnte.[31] Das Zusammenspiel von Musik, Farben und Emotionen beschrieb er unter anderem mit dem Song „Bold as Love“, in dem er darlegt, wie Farben unterschiedliche Gefühle hervorrufen können.[32]

Live-Auftritte

Neben dem reinen Gitarrenspiel setzte Hendrix bei Konzerten zahlreiche Showelemente ein. So spielte er beispielsweise hinter Kopf oder Rücken oder mit den Zähnen. Bekannt ist auch das Verbrennen seiner Gitarre am Monterey Pop Festival. Er setzte den unerwünschten Effekt des Feedbacks, bei dem sich eine Rückkopplung zwischen Gitarre und Verstärker zu einem schrillen Pfeifen aufschaukelt, neben Pete Townshend und den Beatles, als einer der ersten bewusst als Gestaltungsmittel in seinen Songs ein.[33] Besonders bekannt ist die verzerrte, von Hendrix in Woodstock gespielte Variante der amerikanischen Nationalhymne The Star-Spangled Banner. Hier reizte Hendrix auch die Möglichkeiten des Tremolos aus, das in der Zeit vor ihm fast ausschließlich zur leichten Verzierung von Tönen genutzt wurde. Das folgende Beispiel zeigt die Verwendung der sogenannten Divebomb:

Mit Hilfe des Tremolohebels drückt Hendrix die Saiten soweit hinunter (hier sind fünf Halbtöne angegeben), dass sie auf den Magneten der Tonabnehmer zu liegen kommen.

Der Song diente gleichermaßen zur Äußerung von Kritik an der US-Regierung und dem Vietnamkrieg, gegen den Hendrix klar Stellung bezog.

„Sein Instrument jault und kreischt. ‚The Star Spangled Banner‘ – jeder Ton ist eine bittere Anklage, ist tränenreiche Trauer, Protest, ein wütender Aufschrei gegen die zynische Macht des Establishments. ‚Wir sind gegen euren verdammten Krieg im fernen Vietnam.‘ Die Botschaft ist unmissverständlich. Freiheitssehnsucht und Widerstand, alles steckt in ein paar Gitarren-Läufen.“[34]

Seine Kritik setzte er auch textlich innerhalb seiner Songs um. „House Burning Down“ (vom Album Electric Ladyland, 1968) handelt von den Aufständen der Farbigen, etwa während der Watts-Unruhen, bei denen 1965 in Los Angeles einige tausend Menschen verhaftet wurden, oder während der Krawalle in Newark und Detroit 1967.[35]

Equipment

Hendrix spielte bevorzugt Stratocaster-Gitarren der Firma Fender, selten auch Instrumente von Gibson, wie die Flying V und SG. Weil er Linkshänder war, Linkshänder-Gitarren aber Ende der 1960er schwer erhältlich und teuer waren, verwendete er Rechtshänder-Modelle, bei denen er die Saiten in umgekehrter Reihenfolge aufzog. Deshalb befinden sich die Regler und der Vibratohebel bei Konzertaufnahmen auf der oberen, statt – wie allgemein üblich – auf der unteren Seite des Gitarrenkorpus. Er beherrschte jedoch ebenfalls die übliche Spielweise eines Rechtshänders mit normal aufgezogenen Saiten, wobei er Anschlag- und Griffhand vertauschen musste, wie bei einigen Liveauftritten in der Band von James Brown zu sehen ist.

Nach seinem Tod veröffentlichte Fender insgesamt sieben Tribute-Modelle, die jeweils auf wenige Exemplare limitiert wurden. Unter anderem wurden Kopien der Gitarren kreiert, auf denen er in Monterey und Woodstock gespielt hatte.[36] Von Hendrix gespielte Instrumente werden heute unter Fans für hohe Summen gehandelt. Im November 2004 erzielte eine Gitarre 70.000 britische Pfund, umgerechnet etwa 129.000 US-Dollar. Bei der gleichen Auktion wurden zwei leere Zigarettenschachteln für umgerechnet 330 US-Dollar verkauft.[37] Im September 2008 wurde die Fender Stratocaster, welche im März 1967 während eines Konzertes in London von Hendrix in Brand gesetzt worden war, für 280.000 britische Pfund versteigert.[38]

Als Verstärker kamen die meiste Zeit seiner Karriere 100-Watt-Marshall-Verstärker zum Einsatz. Hendrix war einer der ersten Gitarristen, die Marshall-Verstärker benutzten. Er lernte Jim Marshall persönlich kennen und war vom Klang des Verstärkers begeistert. In jüngeren Jahren und im Studio bevorzugte Hendrix auch Verstärker der Firma Fender.

An Effektgeräten hatte er oft modifizierte Geräte wie das „Vox Clyde McCoy“ und „Vox v846 Wah“, das von Roger Mayer entwickelte „Octavia“ (ein Fuzz-Octave-Effekt)[39], das Dallas-Arbiter Fuzz Face und das Unicord Univibe (Chorus und Vibrato) verschiedener Hersteller im Einsatz. Roger Mayer, der damals für die britische Marine arbeitete, entwickelte und passte Geräte Hendrix’ Wünschen an. Zudem benutzte Hendrix oft ein Leslie-Kabinett für sein Gitarrenspiel und den Gesang.

Hendrix' Strat

Es sind im Laufe der Zeit über zehn verschiedene Modelle von Fender erschienen, die an die von Hendrix benutzten Gitarren angelehnt sind. Hierzu zählt ein Instrument für Rechtshänder mit einem Korpus für Linkshändergitarren, die so die Optik von Hendrix Gitarrenhaltung imitiert, jeweils ein Nachbau der Gitarre, die Hendrix beim Woodstock-Festival bzw. beim Monterey Pop-Festival benutzte oder auch eine Rechtshändergitarre mit Linkshänderhals und entsprechend verschobenen Tonabnehmern.

Wirkung

In der Literatur

Der Roman Hymne (2011) von Lydie Salvayre, die für ihren jüngsten Roman mit dem Prix Goncourt 2014 ausgezeichnet worden ist, basiert auf dem Leben von Jimi Hendrix.

Diskografie

Eine vollständige Diskografie von Jimi Hendrix zu erstellen, gestaltet sich schwierig, da es eine große Zahl mitgeschnittener Jamsessions gibt, deren Authentizität nicht immer erwiesen ist. Außerdem gibt es verschiedene Aufnahmen von Hendrix als Begleitmusiker vor seiner Solokarriere. Insgesamt sollen nach Hendrix’ Tod noch mehr als einhundert Aufnahmen veröffentlicht worden sein.

James Marshall "Jimi" Hendrix (born Johnny Allen Hendrix; November 27, 1942 – September 18, 1970) was an American guitarist, singer, and songwriter. Although his mainstream career spanned only four years, he is widely regarded as one of the most influential electric guitarists in the history of popular music, and one of the most celebrated musicians of the 20th century. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame describes him as "arguably the greatest instrumentalist in the history of rock music".[1]

Born in Seattle, Washington, Hendrix began playing guitar at the age of 15. In 1961, he enlisted in the US Army; he was granted an honorable discharge the following year. Soon afterward, he moved to Clarksville, Tennessee, and began playing gigs on the chitlin' circuit, earning a place in the Isley Brothers' backing band and later with Little Richard, with whom he continued to work through mid-1965. He then played with Curtis Knight and the Squires before moving to England in late 1966 after being discovered by Linda Keith, who in turn interested bassist Chas Chandler of the Animals in becoming his first manager. Within months, Hendrix had earned three UK top ten hits with the Jimi Hendrix Experience: "Hey Joe", "Purple Haze", and "The Wind Cries Mary". He achieved fame in the US after his performance at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, and in 1968 his third and final studio album, Electric Ladyland, reached number one in the US; it was Hendrix's most commercially successful release and his first and only number one album. The world's highest-paid performer, he headlined the Woodstock Festival in 1969 and the Isle of Wight Festival in 1970 before his accidental death from barbiturate-related asphyxia on September 18, 1970, at the age of 27.

Hendrix was inspired musically by American rock and roll and electric blues. He favored overdriven amplifiers with high volume and gain, and was instrumental in utilizing the previously undesirable sounds caused by guitar amplifier feedback. He helped to popularize the use of a wah-wah pedal in mainstream rock, and was the first artist to use stereophonic phasing effects in music recordings. Holly George-Warren of Rolling Stone commented: "Hendrix pioneered the use of the instrument as an electronic sound source. Players before him had experimented with feedback and distortion, but Hendrix turned those effects and others into a controlled, fluid vocabulary every bit as personal as the blues with which he began."[2]

Hendrix was the recipient of several music awards during his lifetime and posthumously. In 1967, readers of Melody Maker voted him the Pop Musician of the Year, and in 1968, Billboard named him the Artist of the Year and Rolling Stone declared him the Performer of the Year. Disc and Music Echo honored him with the World Top Musician of 1969 and in 1970, Guitar Player named him the Rock Guitarist of the Year. The Jimi Hendrix Experience was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992 and the UK Music Hall of Fame in 2005. Rolling Stone ranked the band's three studio albums, Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold as Love, and Electric Ladyland, among the 100 greatest albums of all time, and they ranked Hendrix as the greatest guitarist and the sixth greatest artist of all time.

Ancestry and childhood

Jimi Hendrix was primarily of African American descent, and also had Irish and Cherokee ancestors. His paternal great-great-grandmother was a full-blooded Cherokee from Georgia who married an Irishman named Moore. They had a son Robert, who married an African-American woman named Fanny. In 1883, Robert and Fanny had a daughter whom they named Zenora "Nora" Rose Moore, Hendrix's paternal grandmother.[3][nb 1] Hendrix's paternal grandfather, Bertran Philander Ross Hendrix (born 1866), was the result of an extramarital affair between a black woman, also named Fanny, and a grain merchant from Urbana, Ohio or Illinois, and one of the wealthiest white men in the area at that time.[6][7][nb 2] On June 10, 1919, Hendrix and Moore had a son they named James Allen Ross Hendrix; people called him Al.[9]

In 1941, Al met Lucille Jeter (1925–1958) at a dance in Seattle; they married on March 31, 1942.[10] Al, who had been drafted by the United States Army to serve in World War II, left to begin his basic training three days after the wedding.[11] Johnny Allen Hendrix was born on November 27, 1942, in Seattle, Washington; he was the first of Lucille's five children. In 1946, Johnny's parents changed his name to James Marshall Hendrix, in honor of Al and his late brother Leon Marshall.[12][nb 3]

Stationed in Alabama at the time of Hendrix's birth, Al was denied the standard military furlough afforded servicemen for childbirth; his commanding officer placed him in the stockade to prevent him from going AWOL to see his infant son in Seattle. He spent two months locked up without trial, and while in the stockade received a telegram announcing his son's birth.[14][nb 4] During Al's three-year absence, Lucille struggled to raise their son, often neglecting him in favor of nightlife.[16] When Al was away, Hendrix was mostly cared for by family members and friends, especially Lucille's sister Delores Hall and her friend Dorothy Harding.[17] Al received an honorable discharge from the US Army on September 1, 1945. Two months later, unable to find Lucille, Al went to the Berkeley, California home of a family friend named Mrs. Champ, who had taken care of and had attempted to adopt Hendrix. There Al saw his son for the first time.[18]

After returning from service, Al reunited with Lucille, but his inability to find steady work left the family impoverished. They both struggled with alcohol abuse, and often fought when intoxicated. The violence sometimes drove Hendrix to withdraw and hide in a closet in their home.[19] His relationship with his brother Leon (born 1948) was close but precarious; with Leon in and out of foster care, they lived with an almost constant threat of fraternal separation.[20] In addition to Leon, Hendrix had three younger siblings: Joseph, born in 1949, Kathy in 1950, and Pamela, 1951, all of whom Al and Lucille gave up to foster care and adoption.[21] The family frequently moved, staying in cheap hotels and apartments around Seattle. On occasion, family members would take Hendrix to Vancouver to stay at his grandmother's. A shy and sensitive boy, he was deeply affected by his life experiences.[22] In later years, he confided to a girlfriend that he had been the victim of sexual abuse by a man in uniform.[23] On December 17, 1951, when Hendrix was nine years old, his parents divorced; the court granted Al custody of him and Leon.[24]

First instruments

At Horace Mann Elementary School in Seattle during the mid-1950s, Hendrix's habit of carrying a broom with him to emulate a guitar gained the attention of the school's social worker. After more than a year of his clinging to a broom like a security blanket, she wrote a letter requesting school funding intended for underprivileged children, insisting that leaving him without a guitar might result in psychological damage.[25] Her efforts failed, and Al refused to buy him a guitar.[25][nb 5]

In 1957, while helping his father with a side-job, Hendrix found a ukulele amongst the garbage that they were removing from an older woman's home. She told him that he could keep the instrument, which had only one string.[27] Learning by ear, he played single notes, following along to Elvis Presley songs, particularly Presley's cover of Leiber and Stoller's "Hound Dog".[28][nb 6] By the age of thirty-three, Hendrix's mother Lucille had developed cirrhosis of the liver, and on February 2, 1958, she died when her spleen ruptured.[30] Al refused to take James and Leon to attend their mother's funeral; he instead gave them shots of whiskey and instructed them that was how men were supposed to deal with loss.[30][nb 7] In mid-1958, at age 15, Hendrix acquired his first acoustic guitar, for $5.[31] Hendrix earnestly applied himself, playing the instrument for several hours daily, watching others and getting tips from more experienced guitarists, and listening to blues artists such as Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Howlin' Wolf, and Robert Johnson.[32] The first tune Hendrix learned how to play was the theme from Peter Gunn.[33]

Soon after he acquired the acoustic guitar, Hendrix formed his first band, the Velvetones. Without an electric guitar, he could barely be heard over the sound of the group. After about three months, he realized that he needed an electric guitar in order to continue.[34] In mid-1959, his father relented and bought him a white Supro Ozark.[34] Hendrix's first gig was with an unnamed band in the basement of a synagogue, Seattle's Temple De Hirsch, but after too much showing off, the band fired him between sets.[35] He later joined the Rocking Kings, which played professionally at venues such as the Birdland club. When someone stole his guitar after he left it backstage overnight, Al bought him a red Silvertone Danelectro.[36] In 1958, Hendrix completed his studies at Washington Junior High School, though he did not graduate from Garfield High School.[37][nb 8]

Military service

Before Hendrix was 19 years old, law enforcement authorities had twice caught him riding in stolen cars. When given a choice between spending time in prison or joining the Army, he chose the latter and enlisted on May 31, 1961.[40] After completing eight weeks of basic training at Fort Ord, California, he was assigned to the 101st Airborne Division and stationed at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.[41] He arrived there on November 8, and soon afterward he wrote to his father: "There's nothing but physical training and harassment here for two weeks, then when you go to jump school ... you get hell. They work you to death, fussing and fighting."[42] In his next letter home, Hendrix, who had left his guitar at his girlfriend Betty Jean Morgan's house in Seattle, asked his father to send it to him as soon as possible, stating: "I really need it now."[42] His father obliged and sent the red Silvertone Danelectro on which Hendrix had hand-painted the words "Betty Jean", to Fort Campbell.[43] His apparent obsession with the instrument contributed to his neglect of his duties, which led to verbal taunting and physical abuse from his peers, who at least once hid the guitar from him until he had begged for its return.[44]

In November 1961, fellow serviceman Billy Cox walked past an army club and heard Hendrix playing guitar.[45] Intrigued by the proficient playing, which he described as a combination of "John Lee Hooker and Beethoven", Cox borrowed a bass guitar and the two jammed.[46] Within a few weeks, they began performing at base clubs on the weekends with other musicians in a loosely organized band called the Casuals.[47]

Hendrix completed his paratrooper training in just over eight months, and Major General C.W.G. Rich awarded him the prestigious Screaming Eagles patch on January 11, 1962.[42] By February, his personal conduct had begun to draw criticism from his superiors. They labeled him an unqualified marksman and often caught him napping while on duty and failing to report for bed checks.[48] On May 24, Hendrix's platoon sergeant, James C. Spears filed a report in which he stated: "He has no interest whatsoever in the Army ... It is my opinion that Private Hendrix will never come up to the standards required of a soldier. I feel that the military service will benefit if he is discharged as soon as possible."[49] On June 29, 1962, Captain Gilbert Batchman granted Hendrix an honorable discharge on the basis of unsuitability.[50] Hendrix later spoke of his dislike of the army and falsely stated that he had received a medical discharge after breaking his ankle during his 26th parachute jump.[51][nb 9]

Music career

Early years

In September 1963, after Cox was discharged from the Army, he and Hendrix moved to Clarksville, Tennessee and formed a band called the King Kasuals.[53] Hendrix had watched Butch Snipes play with his teeth in Seattle and by now Alphonso 'Baby Boo' Young, the other guitarist in the band, was performing this guitar gimmick.[54] Not to be upstaged, Hendrix learned to play with his teeth, he commented: "The idea of doing that came to me ... in Tennessee. Down there you have to play with your teeth or else you get shot. There's a trail of broken teeth all over the stage."[55] Although they began playing low-paying gigs at obscure venues, the band eventually moved to Nashville's Jefferson Street, which was the traditional heart of the city's black community and home to a thriving rhythm and blues music scene.[56] They earned a brief residency playing at a popular venue in town, the Club del Morocco, and for the next two years Hendrix made a living performing at a circuit of venues throughout the South who were affiliated with the Theater Owners' Booking Association (TOBA), widely known as the Chitlin' Circuit.[57] In addition to playing in his own band, Hendrix performed as a backing musician for various soul, R&B, and blues musicians, including Wilson Pickett, Slim Harpo, Sam Cooke, and Jackie Wilson.[58]

In January 1964, feeling he had outgrown the circuit artistically and frustrated by having to follow the rules of bandleaders, Hendrix decided to venture out on his own. He moved into the Hotel Theresa in Harlem, where he befriended Lithofayne Pridgeon, known as "Faye", who became his girlfriend.[59] A Harlem native with connections throughout the area's music scene, Pridgeon provided him with shelter, support, and encouragement.[60] Hendrix also met the Allen twins, Arthur and Albert.[61][nb 10] In February 1964, Hendrix won first prize in the Apollo Theater amateur contest.[63] Hoping to secure a career opportunity, he played the Harlem club circuit and sat in with various bands. At the recommendation of a former associate of Joe Tex, Ronnie Isley granted Hendrix an audition that led to an offer to become the guitarist with the Isley Brothers' back-up band, the I.B. Specials, which he readily accepted.[64]

First recordings

In March 1964, Hendrix recorded the two-part single "Testify" with the Isley Brothers. Released in June, it failed to chart.[65] In May, he provided guitar instrumentation for the Don Covay song, "Mercy Mercy". Issued in August by Rosemart Records and distributed by Atlantic, the track reached number 35 on the Billboard chart.[66]

Hendrix toured with the Isleys during much of 1964, but near the end of October, after growing tired of playing the same set every night, he left the band.[67][nb 11] Soon afterward, Hendrix joined Little Richard's touring band, the Upsetters.[69] During a stop in Los Angeles in February 1965, he recorded his first and only single with Richard, "I Don't Know What You Got (But It's Got Me)", written by Don Covay and released by Vee-Jay Records.[70] Richard's popularity was waning at the time, and the single peaked at number 92, where it remained for one week before dropping off the chart.[71][nb 12] Hendrix met singer Rosa Lee Brooks while staying at the Wilcox Hotel in Hollywood, and she invited him to participate in a recording session for her single, which included "My Diary" as the A-side, and "Utee" as the B-side.[73] He played guitar on both tracks, which also included background vocals by Arthur Lee. The single failed to chart, but Hendrix and Lee began a friendship that lasted several years; Hendrix later became an ardent supporter of Lee's band, Love.[73]